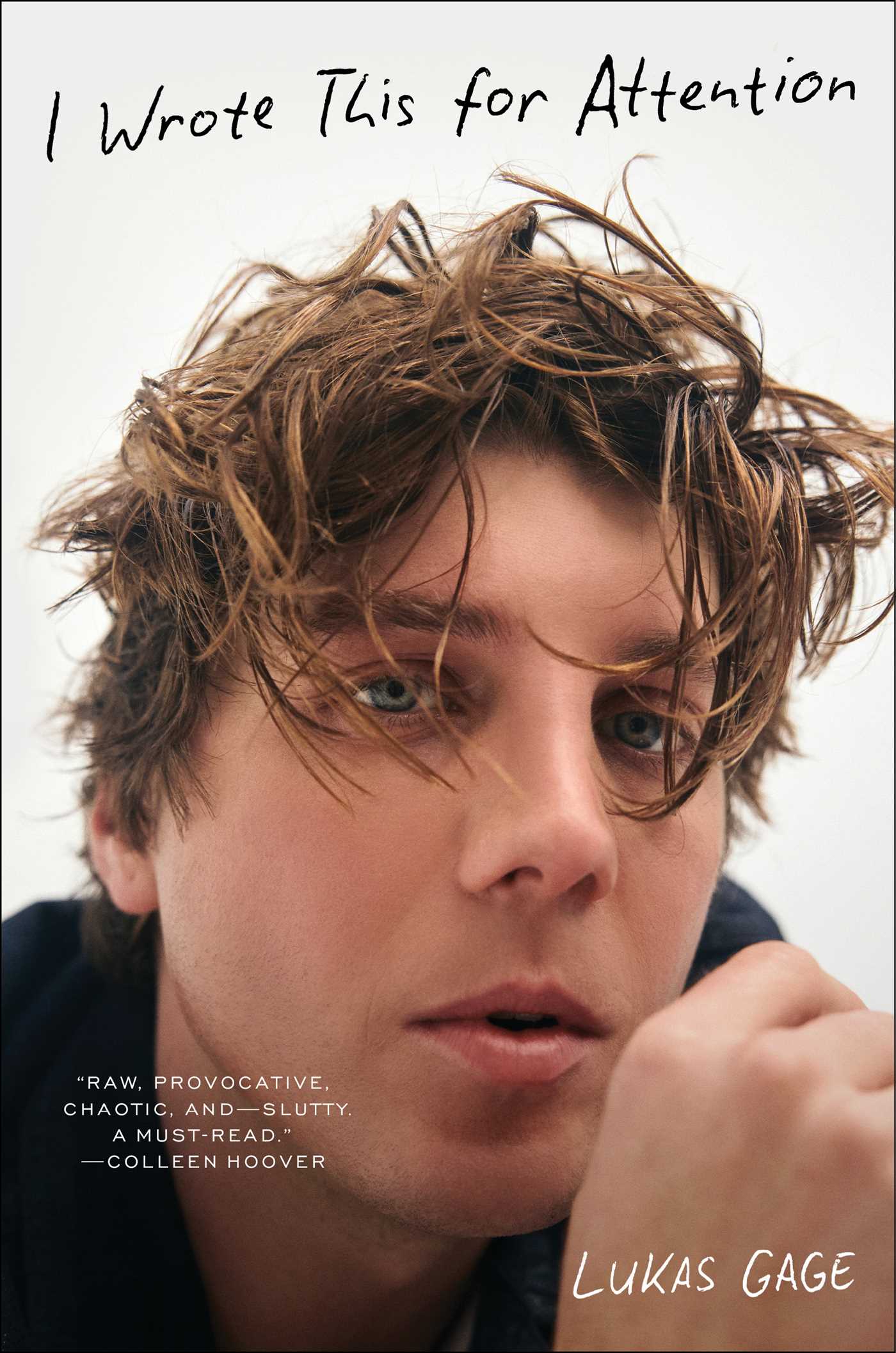

Lukas Gage is nothing if not a very contemporary famous person. He goes from being a total unknown to viral notoriety when a prissy English director is filmed criticising his tiny apartment on Zoom. Then a man on far too many drugs performs anilingus on him in The White Lotus. Then he marries Kim Kardashian’s hairstylist before divorcing him six months later. And now he’s written a memoir at the age of 30, because why not? It’s called I Wrote This for Attention. Everyone told him to call it something else.

“It’s too long, very polarising, and people will hate me for it,” Gage laughs, from his (slightly bigger now) apartment in New York. “But it also meant I could beat people to the punch a little: like, ‘Why did this young person who doesn’t really have a career write a memoir?’”

Gage, of course, does have a career. But it’s a strange and winding one that’s flirted with prestige and, well, the opposite of prestige. You may have seen him being horribly beaten up by Jacob Elordi on Euphoria, or as a delusional Minnesotan in the fifth season of Fargo, or playing a sweet-natured cyborg in this year’s sci-fi chiller Companion. If, however, you are gay or terminally online – or, more accurately, some unholy combination of both – Gage is synonymous with a vociferous internet culture that loves nothing more than to feast on its own. For someone who isn’t (yet) a household name, Gage has been caught in various tidal waves of often inane digital backlash: he’s been with too many women to be a gay man, he’s behaved too celebby to be a real actor, he was too comfortable getting married in an oversized faux fur coat and leather trousers.

“If you’re in the public eye, people are gonna turn on you,” he tells me. “There will be a bandwagon where you become the villain. I’ve had it happen once and I’m gonna have it happen again, I’m sure. But once it does and you get out the other end of it, there’s something very liberating about it. It’s like, wow, I survived that. I’m at peace.”

A little like his good friend Julia Fox, whose career has shapeshifted between legitimate work (like Uncut Gems), memes (like “uncut jams”), and momentary madness (like dating Kanye West), Gage exists in a funny no man’s land between pseudo-stardom and internet infamy. A memoir, then, serves as both a legitimacy-boosting status symbol (Colleen Hoover, purveyor of blockbuster weepies, supplied a glowing blurb), and a chance to wrestle back control of a narrative run amok. Fox, whose own searing memoir Down the Drain was one of the unexpected non-fiction treats of 2023, was a big supporter of Gage writing his own. “When she read it, she said she felt like we’re soul sisters,” he beams. “And that was all I needed, because she’s a genius.”

I Wrote This for Attention may have been a product of temporary unemployment (Gage pitched it to publishers during the dual actors and writers’ strikes of 2023), but it’s also a boon to a rising star who so nearly became more of a Twitter celebrity than a real artist. The book gets to the crux of him, from his tumultuous childhood in Encinitas, California, just 25 miles from the Mexico border, to his early struggles with drugs and alcohol, and the sexual abuse he experienced at a pre-teen summer camp. It’s often a very funny coming-of-age story, rooted in the plasticky excess of the Noughties (Curious by Britney Spears wafts through the air; Paris Hilton and Lindsay Lohan are cultural touchstones), but also bleak and unsparing. While young Hollywood is currently filled with nepo babies and the comfortably well off, Gage’s background is comparatively rocky and dangerous. His older brother battles addiction, his mother is magnetised to casinos, his father is disgusted when a four-year-old Gage slips into heels and Playboy bunny ears and dances around their living room.

“We were a deranged little unit, with so much love for one another but also so many issues,” he remembers. “I come from a world where people are punished for needing help, and encounter systems that continue to fail so many.” At one point he is sent to a “troubled-teen” camp, which reads like a kind of legal torture den for adolescents. Today, he says, his relationship to drugs is nuanced. “I wouldn’t say they’re a friend or an enemy, but like a roommate I outgrew. They gave me some of the best nights of my life and also some of the worst.” Opiates, though, continue to horrify him. “I know people in my hometown that still struggle with them, and I’ve seen them cause the most trouble and the most damage overall. I hate, hate, hate them.”

Gage is a careful conversationalist, and more soft-spoken and uncertain about himself than I imagined. He’s also far more sincere and vulnerable than I imagined, too – he is 30 now, but seems younger. He first moved to Los Angeles at the age of 18 to pursue acting, finding in it a legitimate means to satisfy his lifelong thirst for attention. “I was a little boy desperate to be seen, loved and validated,” he says. “And then I became a man desperate to be seen, loved and validated.”

Gage’s relationship to fame is, by his own admission, nonsensical. He pines over Noughties celebrities for their “authenticity” and how little they seemed to be driven by “Instagram, iPhones and brand deals”, but is also quick to plug Tommy Hilfiger, Armani and La Mer skincare on his own social media pages. He wants fame, but not the sort of fame that’s all “virality and memes”. “Being discovered as an actor felt like the fulfilling of a dream I’d sweated over all of my life,” he says. “But then being discovered as a public figure felt unearned and accidental. It felt exposing, and loud, and where all of that overlaps and intersects has never really made sense to me.”

Point out the contradictions of it all, and – to Gage’s credit – he holds his hands up. Then he quotes Walt Whitman. “‘Do I contradict myself? Very well then I contradict myself. I am large and I contain multitudes.’”

He laughs, rubbing his eyes. He apologises. He only woke up an hour ago, and is inhaling a smoothie.

“The one thing I get scared of is people being all, ‘Wait, you said this back then, and now you’re saying something else,’” he says. “But that’s only because I’m growing and changing all the time. My perspective on things will evolve or shift, or not make any sense, and I feel like that’s OK.”

A few years ago, Gage was diagnosed with borderline personality disorder, which manifests in the form of mood swings, self-destructive, impulsive behaviours and a pattern of unstable, short-lived relationships. “It reframed everything for me,” he says. “My past relationships. The self-sabotage. All the highs and lows. Suddenly there was this map, and I could see patterns. It wasn’t just that I was ‘chaotic’.”

Part of him is nervous about having gone public with it. “I don’t want to have a scarlet letter on me and walk around with this thing. But I also know that I’m not broken, and that I’m not a liability. I can be a good person. I’m just wired differently.”

In 2024, Gage appeared on Andy Cohen’s US talk show and described his short-lived marriage to hairstylist Chris Appleton in 2023 as “a manic episode” – it seemed a joke at the time, but his book confirms it to be more or less true. They loved one another, but moved far too fast. They had met, gotten engaged, married, and announced their separation all in the space of nine months.

“I feel like I got swept up,” he says. “Part of me was rebelling against this backlash I was experiencing.” Online, Gage had been accused of “queerbaiting” after a viral tweet accused him of being a “non-LGBTQIA+ actor” who, despite that, had played queer characters on a number of TV shows. Gage wasn’t out at the time, and was privately still figuring out his sexuality. And, frankly, he was pissed off. Don’t believe he’s gay? Well, watch him propel himself into a very well-photographed marriage to a Kardashian-adjacent male micro-celebrity, then.

“I lashed out in this very public way that didn’t feel authentic to me,” he says. “Then, suddenly, this relationship overshadows all the work I’d done and the career I was building.” Then that drew a backlash. “People thought, ‘Oh, he’s just doing this for jobs and clout-chasing and to make his way to the top.’ But, in actuality, it was a detriment to my career. At the time, the feedback I was getting from casting agents was that I had too much of a public persona. People wouldn’t let me audition for things…”

He stops, and restarts his thoughts. “I don’t know what I’m trying to say,” he whispers. We sit in silence for a second. “On some level, I just didn’t want to be closeted anymore. But the way I went about it was very polarising. I’ve learnt that it’s so much more beneficial to not have as much of your personal life out there. It’s better to have that mystery.”

We sit in silence.

“And then I, you know, write a book.” Gage laughs, rubbing his brow. I sense this is all a lot for him. Gage is famous but not. Straight-passing but gay. Thirsty but terrified. “I want fame, recognition and validation,” he says. “And then I get it and it scares me and I’m like, ‘Don’t look at me, I don’t want it anymore.’”

For now, at least, he is content with his contradictions. He is large, and he contains multitudes.

‘I Wrote This for Attention’ by Lukas Gage is out now, via 4th Estate