The West Coast is years overdue for the next big earthquake.

When the colossal tremor eventually strikes, seismologists expect high-rises and other buildings to collapse, massive fires that can burn hundreds of homes, Los Angeles highways to buckle and potentially a tsunami that could block any rescuers from reaching the tens of thousands of people who are threatened.

But, as it turns out, that’s “not the worst case scenario,” Chris Goldfinger, a marine geologist at Oregon State University, said in a statement.

Goldfinger and a group of international researchers have found a connection between two major West Coast faults and they say it could trigger double the devastation.

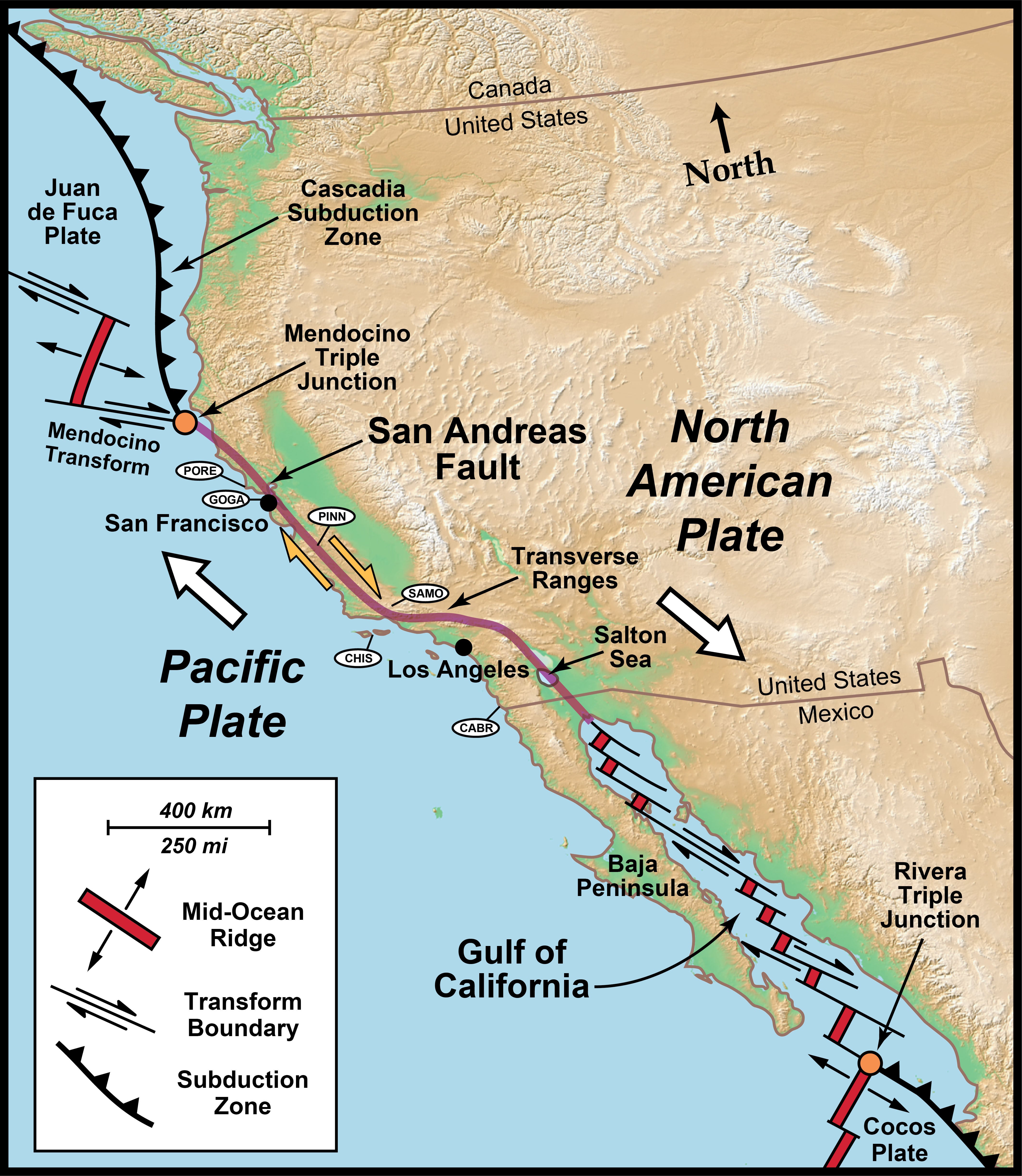

The Hollywood-featured San Andreas fault and the Pacific Northwest Cascadia subduction zone may be in sync, they explained, with potentially disastrous consequences for residents of California, Oregon, Washington state and Western Canada.

“We could expect that an earthquake on one of the faults alone would draw down the resources of the whole country to respond to it,” Goldfinger said. “And if they both went off together, then you’ve got potentially San Francisco. Portland, Seattle and Vancouver all in an emergency situation in a compressed timeframe.”

Altogether, the four cities are home to nearly 3 million people, although there are many more who live on areas of the coast outside of the major metros.

When this all could go down remains the lingering question – until it doesn’t. Often, there may only be 200 years between earthquakes on these faults.

The last major quake on the Cascadia Subduction Zone was in 1700, when a magnitude 9.0 quake triggered 30-foot-high Pacific waves that hit Japan. The probability of a similar quake in coming decades is about one in eight, according to the Penn State College of Earth and Mineral Sciences.

This event was followed by a magnitude 7.9 earthquake on the northern San Andreas fault, the researchers said.

“What that suggests is that the San Andreas earthquake happened very closely in time after the Cascadia earthquake,” Jason Patton, an engineering geologist with the California Geological Survey who also worked on the research, told The Los Angeles Times.

The ruptures could have been just minutes or hours apart, according to Goldfinger.

And they found all of this out largely through happenstance. When drilling sediment cores deep in the ocean’s floor in 1999 in the Cascadia subduction zone, a navigational error sent Goldfinger and the research team off course and into the San Andreas zone. So, they decided to drill a core there, as well.

Comparing the composition of the cores from both fault systems revealed similarities in timing and structure over 3,100 years that resulted in them linking the seismic impacts.

Goldfinger and the researchers hope their findings will help West Coast leaders better prepare, whatever the future may bring.

“Our preparedness level is poor,” Goldfinger told The Guardian. “We have a long way to go, and all these areas were built on top of ticking time bombs.”