A father who set himself alight in desperation as his mental health crumbled while serving 13 years in prison for stealing a phone has finally been transferred to hospital.

Thomas White, who is serving an abolished indefinite jail term described by the United Nations as “psychological torture”, developed paranoid schizophrenia and psychosis in prison as he lost hope of being freed from his imprisonment for public protection (IPP) sentence.

Last year, The Independent revealed how he had set himself on fire in his cell as this newspaper backed his family in their six-year battle for him to be transferred for inpatient mental health treatment.

In March, we revealed how he had suffered yet another mental health crisis, in which he repeatedly smashed his face on the floor of maximum-security HMP Manchester, where he was being held.

This week, the 42-year-old father of one finally arrived at a specialist medium-secure unit in Northumberland – where his family hopes he will finally get the help he needs – three months after he was approved for the transfer.

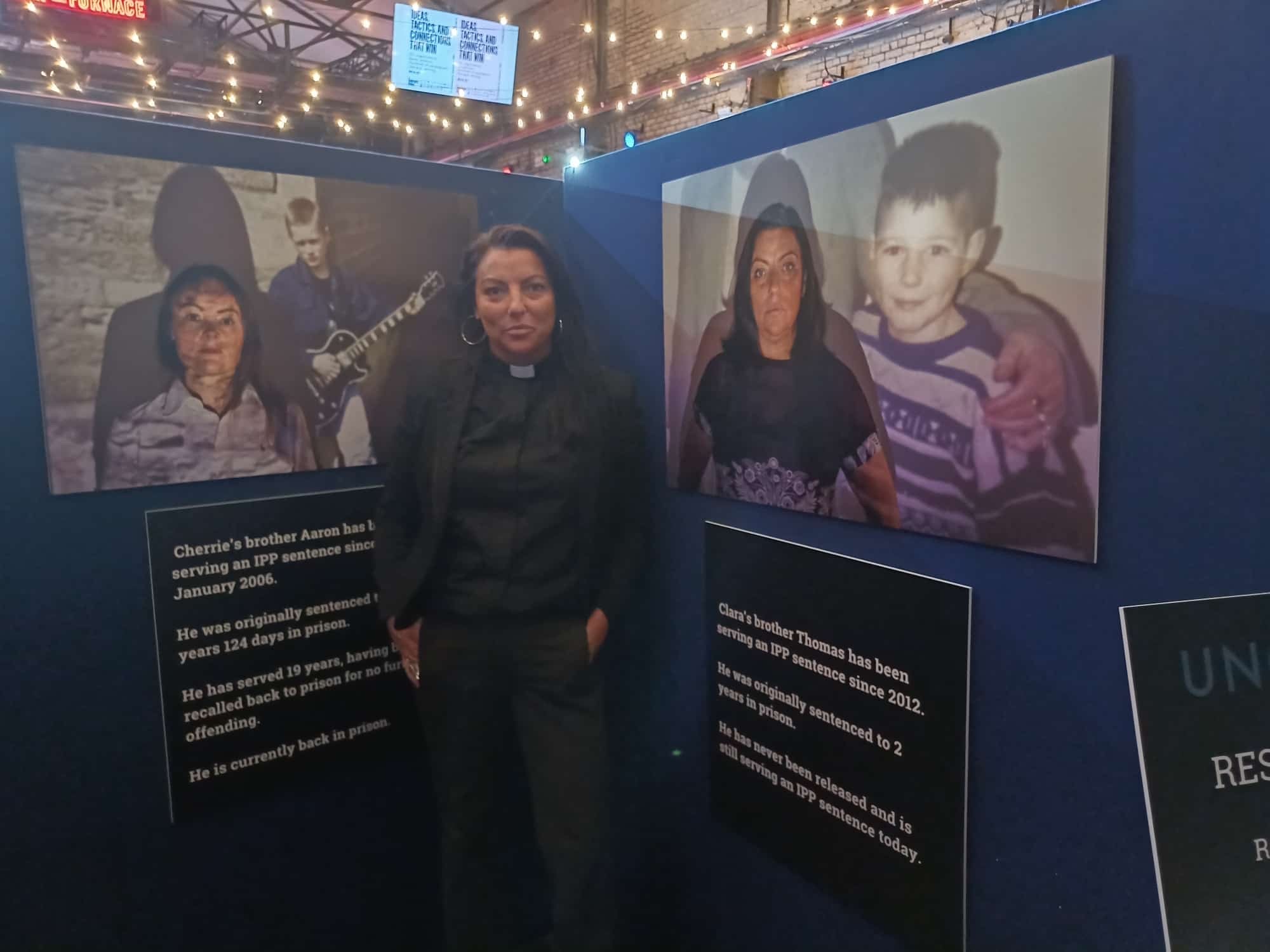

His sister, Reverend Clara White, told The Independent: “He keeps saying, ‘Clara, thank you, thank you, thank you, I would have died in prison.’”

The transfer comes after he spent 13 years languishing on the controversial open-ended jail term. IPP sentences were scrapped in 2012 following a damning ruling from the European Court of Human Rights, but not retrospectively, leaving thousands of inmates trapped in jail for years beyond their original prison terms.

White, who had previous convictions for theft, was handed an IPP sentence with a two-year tariff for robbery just four months before the sentences were outlawed. Then aged 27, he had been binge-drinking when he took a phone from two Christian missionaries in Manchester.

Thanks to the indefinite jail term, he has remained incarcerated as his mental health has deteriorated. He moved prisons 12 times and was banned from seeing his only son, Kayden, who is nearly 16, for most of his prison term.

Three psychiatrists had called for White to be moved to a hospital to treat his mental health. The latest, on 13 February, concluded he was “struggling in the prison environment” and it was likely “he is deeply frustrated and angry as a result of his predicament”.

Two medical reports last year laid bare the toll of the devastating IPP jail term, warning that White’s “lengthy incarceration” was creating “impermeable barriers” to his recovery.

Rev White, who was this month ordained as a pastor, said she was still struggling to process the news that he was finally in hospital after she took the fight to the Ministry of Justice.

David Blunkett, who admits he regrets ever introducing the jail term when he served in Tony Blair’s Labour cabinet, joined efforts to help White get visits with his son.

Meanwhile, prisons minister James Timpson personally visited him inside the category A jail where he was being held after Rev White raised awareness of his plight.

“It definitely has been a victory but I have to remember that he’s gone from one institution to another institution and it may take a long time to get him well,” she added.

“We have been dragged from pillar to post. I feel like I have had a mental beating along with Thomas.”

Although her brother is still struggling with religious delusions at the unit, she takes comfort from the knowledge that “he’s in the right place now”.

However, she fears she will still need to fight to keep him there for longer than six months.

Of almost 2,500 people still incarcerated on an IPP jail term, nearly 700 have served at least 10 years longer than their original minimum term.

Successive governments have refused to resentence IPP prisoners, despite calls from the justice committee and the UN special rapporteur on torture following high rates of suicide and self-harm.

The MoJ insists it will not consider releasing prisoners who have not passed the Parole Board’s release test.

This week Nazanin Zaghari-Ratcliffe, who was detained in Iran for almost six years, joined calls for the government to act to help those still languishing on the sentence.