One year has passed since the death of my dad. We were very close. The rawness of my grief has started to feel less intense, allowing me the space both to consider the true dynamics that were at play in my family when I was growing up, and to put a name to the perhaps less flattering ones.

I come from a large family of five half-siblings: I was the youngest, and a “love child”. My mother died 20 years ago. Blended families tend to be fraught with challenges, and we certainly had our share. The big house in Richmond where we lived looked perfect from the outside, and sometimes it was perfect on the inside, too, serving as the backdrop to many happy childhood memories. But it was also, as I have recently come to realise, host to a set of conflicting personalities, centred around one parent with narcissistic traits: my father.

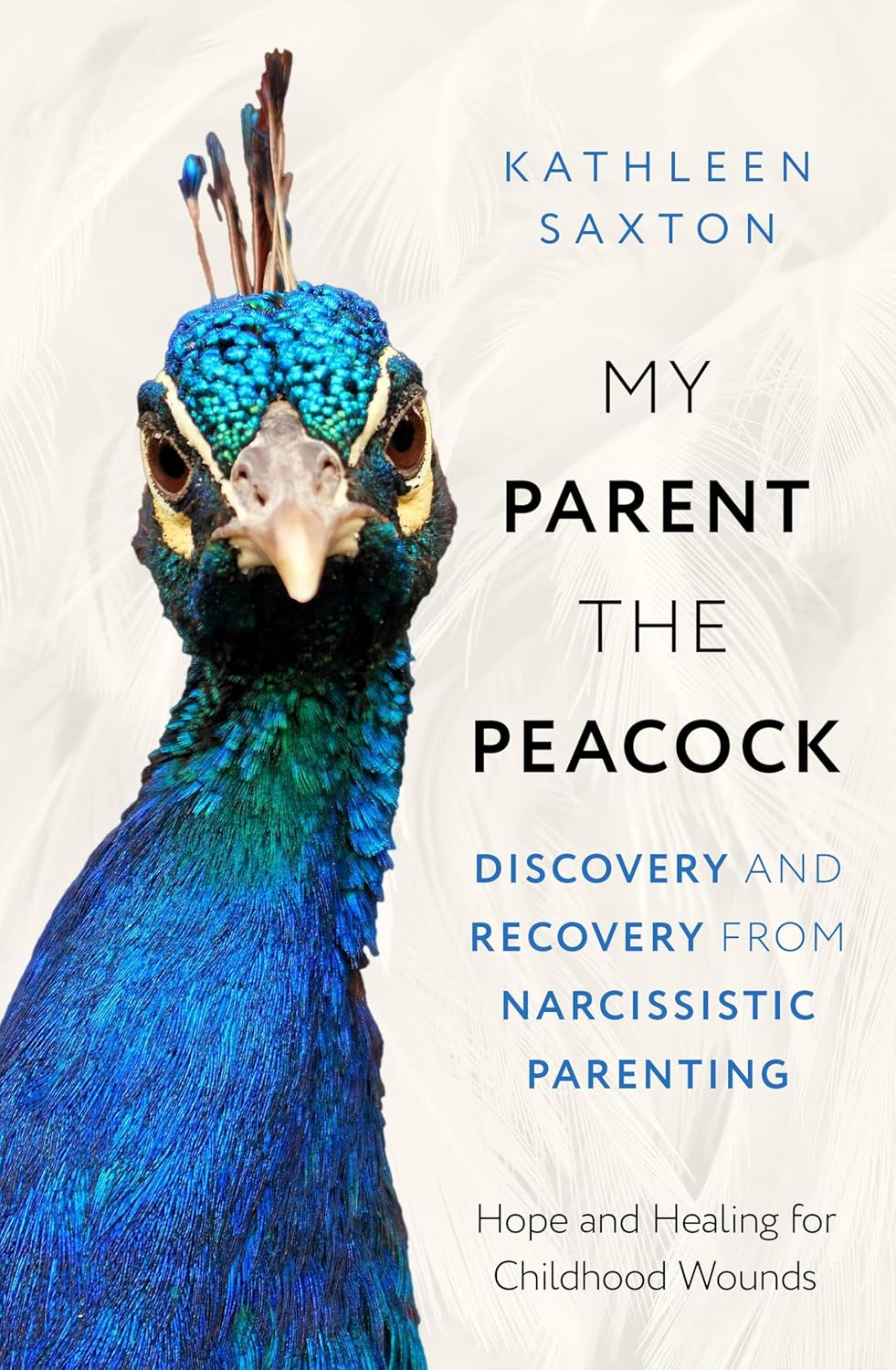

I’d always imagined a narcissist as someone evil and grandiose – certainly not like my kindhearted and generous-spirited dad – but since reading Kathleen Saxton’s My Parent the Peacock: Discovery and Recovery from Narcissistic Parenting, it’s come to light that he was probably one of the estimated 12 per cent of people in the UK who fit the bill. Meanwhile I was a hapless victim, playing the familial role of the “golden child”. This archetype is idealised and placed on a pedestal; I had to be a star student, and good looks were everything. While a “golden child” like me appears to benefit from the favoured position, it’s a role that comes with huge pressure and unrealistic expectations. My self-worth became linked to my ability to please my dad, from whom I sought constant approval.

If there’s even one narcissist in the family, it’s like a pebble in the water, says Saxton, who as well as being an author is an acclaimed psychotherapist. Published this month, her book offers a compelling portrait of narcissism. She uses a mix of science and compassionate case studies to help readers make sense of a personality trait that can be found everywhere – in the workplace, in romantic relationships, and in the home.

“It impacts the whole family with a ripple effect,” she tells me. In a narcissist’s family, each child is assigned a role that enables the narcissist to live their idealised life – whether that’s the golden child, the lost child, the scapegoated child, or even the comedic child. Whatever position they’re assigned, children will compare roles, and think their siblings got the better deal. In the case of my family, my dad also used “triangulation” – a process by which he pitted us against one another, causing intense sibling rivalry, which in turn gave him more control.

.JPG)

Saxton describes the assignment of these roles as a form of “identity theft”, whereby the child is unable to develop their true self because they are forced to adopt the traits imposed by the narcissistic parent in order to maintain that parent’s idealised version of reality.

In my dad’s case, his narcissistic sheen meant that us children always had to be jolly and happy. True feelings, and “ugly” feelings, were swept under the carpet and never spoken of. As a result, growing up, we each self-medicated in our own way: work, food, alcohol, and prescription drugs. For me it was alcohol. According to Saxton, it’s likely that my dad insisted on the happy family narrative because a harmonious household would help absolve him of the guilt and shame he felt about splitting from his first wife and leaving his young kids in order to be with my mum – and have me.

With her book, Saxton seeks to demystify narcissism, something she says is greatly misunderstood. “While NarcTok and social media have successfully highlighted what has been recognised as a diagnosable personality disorder since 1980, it has become too easy to call someone a narcissist when they are just a bit selfish or disagreeable,” she says. “The challenge of this is that those who have truly suffered around one may not be getting the support, help and understanding they need.”

It’s important to remember that there are several types of narcissism, says Saxton. “What’s becoming clear is that the better-known flavour of narcissist – the grandiose type, full of self-proclaimed brilliance, [showing] a total lack of empathy, and enraged by criticism – is only part of the story,” she explains. There’s also the “covert” narcissist, who is often hidden in plain sight and gains their “narcissistic supply” – that is, the attention they desire – through a more introverted, quieter form of victimhood. “Always showing sacrifice, and gaining pity and admiration; often blaming others.” As parents, Saxton continues, “they very often use their children as both positive endorsers, by showing them off as a good reflection on their parenting, or as a shield to deflect negative rumours”.

Most of us carry traits of narcissism, which include “a need for admiration, selfishness, and some struggle with criticism and empathy”. The other forms of it, however, are rarer: there are those who have a narcissistic personality, in which narcissistic behaviours are commonly seen on a daily basis, and then there is narcissistic personality disorder (NPD), an extreme version of narcissism, which is ever-present, incurable – and insufferable. “When you are in the presence of the disordered type, you most certainly know that something is not right,” says Saxton.

My dad didn’t have the disordered type, I’m sure. From the descriptions in Saxton’s book, it seems likely that he had the less extreme, more pervasive “narcissistic personality”, meaning he could have sought treatment in therapy – but being unaware of the label, and out of touch with the deep-seated emotional factors behind his behaviour, he didn’t.

Those suffering from NPD have no such hope. Despite much research in the field, there is as yet no known or accepted therapeutic treatment for the condition. “Deep down it is very sad that anyone develops this disorder, as it stems from an emptiness of self – which is heartbreaking for the narcissist, too,” says Saxton. “They just don’t realise it, and that gap unfortunately brings terrible suffering to those who often love them the most.”

Growing up, any sadness I expressed was interpreted as ingratitude, and anger was discouraged as shameful. This was all in the name of maintaining a perfect facade – or as Saxton refers to it, “the beauty of the peacock plumage”. I was neglected because my mother took on the caretaker role for the children from my father’s past relationship, having been told by him to treat them no differently from her own. He wanted ours to be a big, fair, and perfectly happy family – like the Waltons on TV.

I finally imploded aged 20, and went into rehab for alcoholism. When I entered recovery at 24, I didn’t know who I was – or how to identify my feelings. It took years of work for me to accept myself. The rest of my family seem to have stayed in denial that anything was wrong.

Certainly, it’s left me wondering whether, as a golden child, I’m at risk of inheriting my dad’s narcissistic traits. Could I be a narcissistic parent to my own children? “Golden children are susceptible to developing such traits, given they are often lauded as being ‘special’ by their narcissistic parent,” says Saxton. “They can become entitled – and they come down to earth with a bump at the point when our normal, fallible selves are put into the world.” Needing therapy, for example, could be that wake-up call. In my case, I had a bigger bump than most, moving from golden child directly to the stark truth of rehab, where I connected to my true self in the rawest of ways. I knew addiction was a family illness – now I see narcissistic parenting as being entwined with it.

As for whether I’m a narcissistic parent myself, Saxton reassures me that any parent who even asks that question – or who finds themselves apologising to their children for their parenting mistakes, as I often do – is unlikely to possess any meaningful form of narcissism. “That’s because the majority of those afflicted with either form of narcissism [personality or disorder] would not have a strong enough ego to tolerate the notion that they could be narcissistic,” she says. This brings us to a common misconception about narcissists, which falsely assumes they have a large ego. In fact, she says, “a narcissist’s ego is empty and shattered – hence why they feel the need to put up a persona, or curate a perfect life, in order to gain respect and admiration”.

Ultimately, the work of a golden child is the same as that of any child: to finally find their own voice and speak up. I have had to learn that I’m good enough just as I am, on good days and bad. I’ve had to stop relying on external validation for my self-worth, and learn to accept my true self. It’s not an easy journey – and it’s a daily battle. But once I found myself, there was no looking back.

‘My Parent the Peacock’ by Kathleen Saxton is published by Sheldon Press, £15.99