A young man from Eritrea has manoeuvred his small boat straight through the government’s “one in, one out” migration agreement with France, with a legal plea that could sink the whole policy. So far, two flights intended to carry the first deportees this week have carried none.

The decision of a High Court judge to grant the unnamed 25-year-old time to make his case against deportation undoubtedly inflicts a huge blow on the agreement negotiated by Yvette Cooper, then the home secretary, with her French counterpart back in July. A large part of the rationale for that agreement was to exclude such appeals and the resulting delays in removing those found ineligible to stay.

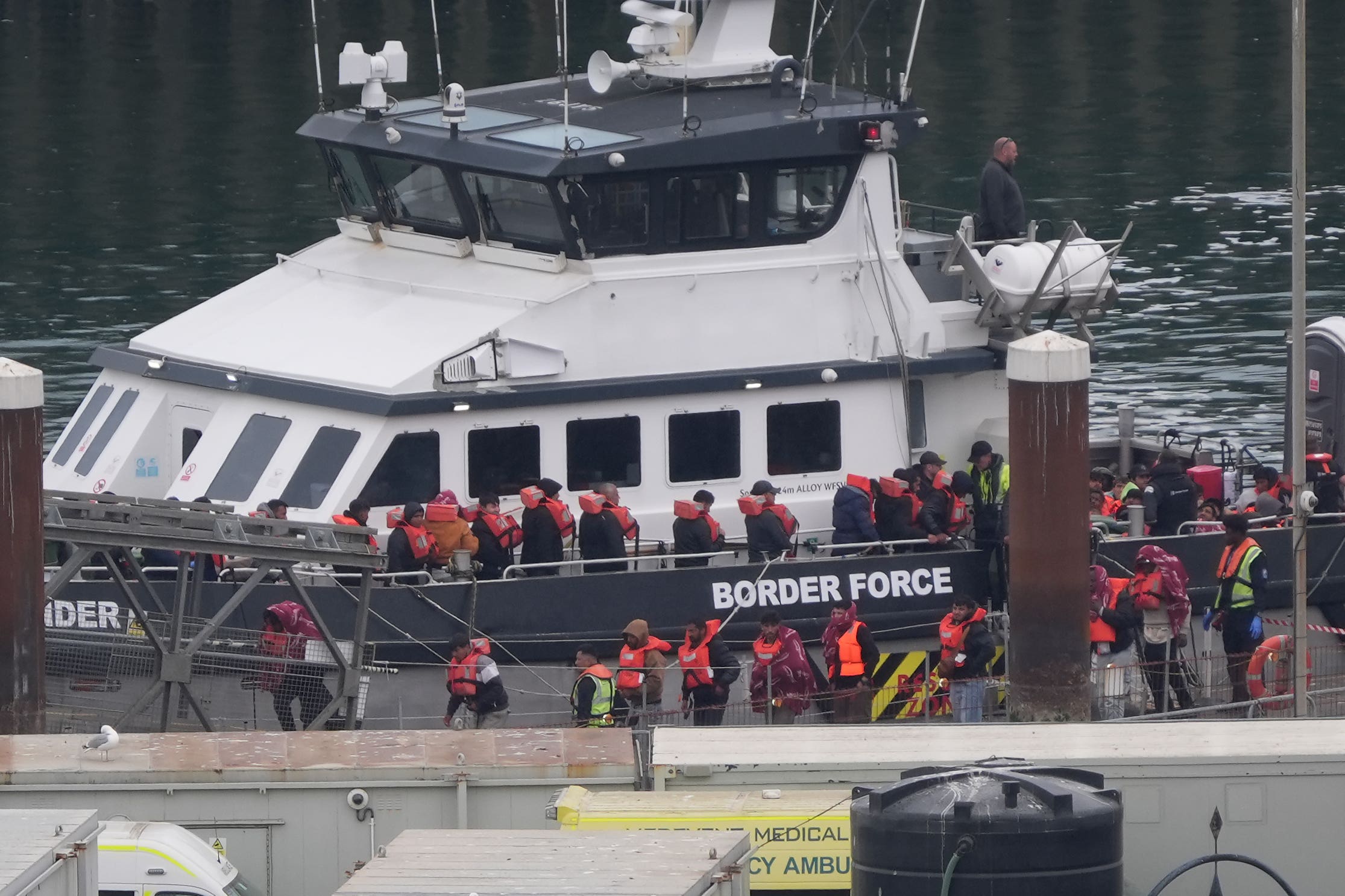

Under the agreement, certain small boat arrivals are separated from the rest and detained pending deportation to France within 14 days. France may reject individuals based on specific criteria, but the overall purpose is to establish a fast-track system of deportation, initially for a small number, with the potential for “scaling up”. In return, the UK will accept an equivalent number of non-boat people in France with links to the UK.

Now, we could be back at square one, because the agreement cannot override internationally guaranteed human rights enshrined in the post-Second World War Geneva Conventions.

For those campaigning for lower migration overall, the concept was never satisfactory, as it simply exchanged one small group of would-be migrants for another to be admitted legally into the UK. The government’s argument was that it would become a deterrent to those who currently see small boats as their best hope of reaching the UK.

This week’s tally of 12 boats carrying nearly 900 people, and no removals to France, is not one that a government under growing pressure from Reform UK and an increasingly restive public would have wanted to see. If the “one in, one out” principle was the best that could be extracted from a France that has no interest whatsoever in taking back would-be migrants, there needs to be some evidence that it could work. Instead, it leaves some serious questions that you don’t, by the way, have to be a so-called “lefty” lawyer to ask.

By what right, for instance, are some small boat arrivals detained before deportation to France, and how are they chosen? In the past, the Geneva Conventions were cited as precluding the detention of those seeking asylum. Why is this provision suddenly being selectively applied? The agreement with France states that those detained will be “individuals who, upon arrival, do not or no longer fulfil the conditions for entry to, presence in, or residence in the territory of the UK”. That says nothing specific about the criteria to be applied.

The British public have also been given no idea of how many people have been detained pending removal to France. Such information, we are told, must remain confidential, because its release would give valuable information away to the “gangs” that Cooper so singularly failed to smash. But the young Eritrean, who is reported to have asked why he was detained while most of the others on his boat went free, had a legitimate complaint. To know why you are subject to a particular provision is a basic principle of justice in any law-governed system. What is more, parliament and the people have a right to know, too.

If the government wants to convince a sceptical public that the agreement with France is worth the paper it is printed on, it will need to provide them with a great deal more information than it has so far. This, in turn, is only likely to fuel calls for the UK to leave the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR), an institution that is hated in some quarters only because it has “European” in its name, though it has no association with the EU.

Criticism of the ECHR tends to focus on Article 8 of the European Convention on Human Rights, which provides for the right to a family life. As home secretary, Cooper commissioned a review into the interpretation of this legislation in the UK, which is still in progress. But reports from France, Germany and Denmark suggest that judges there may take a less generous view than their UK counterparts, and give more weight to what they see as the interests of the resident population than to those of the newcomer. In other words, any problems may lie as much with sections of the UK judiciary as with these international jurisdictions. In that case, leaving them would not be the answer.

This latest failure has come at a relatively good time for the Starmer government. What with the Trump state visit, the Peter Mandelson furore, and parliament just starting another recess for the party conferences – a luxury, by the way, not enjoyed by parties elsewhere, which must fit their conferences into existing breaks – it will be nearly three weeks before any serious political questions are asked.

In the meantime, it is just possible that one particular Eritrean will have landed in France. Proof, or so ministers will say, that the agreement with France is succeeding, even if its actual workings remain legally murky, both to the UK public and to those singled out for return.