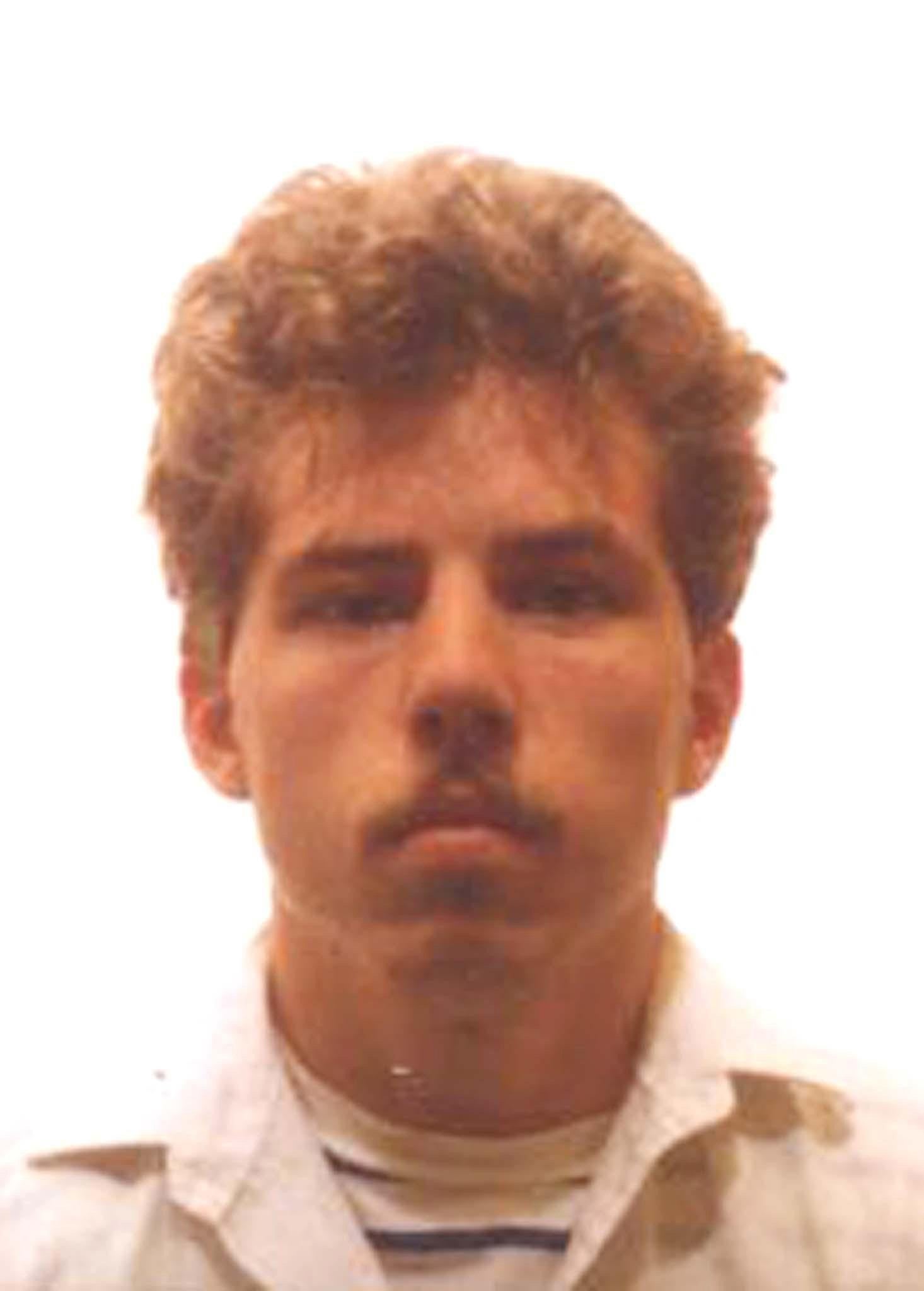

On 16 November 1989, 25-year-old Billy Dunlop strangled 22-year-old pizza delivery girl and mother-of-one Julie Hogg to death, and hid her corpse behind a bath panel in her home in Billingham, County Durham. She was found decomposing by her mother Ann Ming 80 days later and, despite evidence against Dunlop, juries twice failed to find him guilty of the crime. He was acquitted and released.

While in jail for another violent offence, Dunlop boasted to a prison guard about getting away with the killing. He was sentenced to six years in jail for perjury – but couldn’t be prosecuted again due to the double jeopardy law: 800-year-old legislation, which protects individuals from being tried for the same crime multiple times if new evidence emerges. Ming vowed to overturn this law, to win justice for her daughter. “It was horrible – he was bragging in pubs about committing the perfect murder,” she said. “I was absolutely incensed.”

The infamous case is being dramatised in I Fought the Law, a new four-part ITV series, based on Ming’s book, For the Love of Julie. It stars Sheridan Smith as Hogg’s mother, who embarked on a 15-year-long fight to change Britain’s double jeopardy law and put Dunlop behind bars. Ahead of the show’s launch, here’s the real-life story…

The murder

Dunlop killed Hogg after a night of partying at Billingham rugby club, where he’d been binge drinking and harassing strippers. After getting into a fight, Dunlop went to hospital for an eye injury, was discharged, and visited Hogg – whom he knew from the local area – at home, expecting sex. Hogg declined Dunlop’s advances and made a joke about his eye, he later told officers. He spun into a rage and strangled her to death, in what prosecutors called a “truly horrendous” attack.

The search for Julie

Ming reported her daughter missing the day that she was killed. She’d driven over to Hogg’s house and “immediately” knew something was wrong when the curtains were closed and doors were locked. Police wouldn’t officially consider Hogg missing until two days later. A week later they agreed to send round a forensics team to her house. The officers searched for five days and found nothing suspicious, promising Ming nothing “untoward” had happened to her daughter in the property.

Three months after Hogg’s disappearance, Ming agreed that Hogg’s husband, who she’d been in the process of separating from when she was killed, could move back into her daughter’s house with their three-year-old son, Kevin. When her son-in-law entered the property, he complained a strange smell was coming from the bathroom. Ming noticed the bath panel was loose and pulled it away, uncovering her daughter’s body, wrapped in a blanket: “That was the start of a living nightmare,” she said.

When police searched Hogg’s house for a second time, they discovered her bank cards and diary hidden in the loft. A full-scale murder investigation was launched and officers began looking into men Hogg had recently been linked to. The DNA on the blanket she was wrapped in ruled out all but one: Billy Dunlop, who lived two streets away. Hogg’s keys were found hidden under his floorboards and he was arrested on 13 February, 1990 – 89 days after she vanished.

The trial

Dunlop went on trial at Newcastle Crown Court on 7 May 1991. There was finger print evidence on Hogg’s keys, his sperm was on the blanket he’d wrapped her in, and there were fibres from the jumper he’d been wearing at the rugby club at the scene. The prosecution team felt it was sufficiently strong evidence to satisfy a jury – but they were wrong. The jury failed to reach a verdict and the judge ordered a retrial for 3 October 1991.

Dunlop’s defence team attempted to convince the jury Hogg had died of natural causes following a consensual act at the second trial. The jury failed to reach a verdict for a second time and Dunlop was acquitted and could never be trialled again due to the double jeopardy law. He walked out a free man and weeks later, Ming heard he’d been publicly bragging about killing her daughter in their town.

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 day

New subscribers only. £8.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled.

Try for free

ADVERTISEMENT. If you sign up to this service we will earn commission. This revenue helps to fund journalism across The Independent.

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 day

New subscribers only. £8.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled.

Try for free

ADVERTISEMENT. If you sign up to this service we will earn commission. This revenue helps to fund journalism across The Independent.

Dunlop’s confession

In 1998, while Dunlop was serving time in prison for attacking another woman, he wrote letters to his ex and a friend admitting to Hogg’s murder. The police wanted to arrest him for perjury but needed more evidence than a simple admission. So, a female prison officer wore a wire and obtained 90 hours of material about what happened on the night of Hogg’s death. He was arrested, pleaded guilty to the murder, and jailed for six years to be served consecutively to his existing sentence.

Ann’s fight for justice

Ming wasn’t satisfied with Dunlop’s perjury sentence and asked her MP, Frank Cook, to help her meet Home Secretary Jack Straw to change the double jeopardy law. He recommended she speak to the Law Commission and, in 2002, her 13 years of campaigning finally broke through.

A white paper advising changes be made to the legislation, to affect both future and retrospective cases, was presented in parliament by David Blunkett, and in April 2005, the 800-year-old law was scrapped. Ming told reporters at the time: “I just can’t believe it. For once in my life I’m speechless.”

In September 2006, Dunlop went on trial at the Old Bailey, was found guilty and sentenced to life behind bars. All his requests for parole and to be moved to an open prison have been denied.

Meanwhile, Ming, now 79, was awarded an MBE for changing the double jeopardy law in 2007. She said of the honour: “I’d have given anything to have my daughter [back] instead of getting a badge.”

I Fought the Law debuts on ITV at 9pm on Sunday 31 August.