For three days in July, folk songs and drumbeats echoed around a quiet village perched high in the Indian Himalayas as hundreds of people gathered to celebrate a wedding. What drew the large crowd – and soon national attention – to the hamlet of Shillai in Himachal Pradesh state was that Sunita Chauhan was marrying not one man but two: brothers Pradeep and Kapil Negi.

The wedding ceremony on 12 July was solemnised in accordance with Jodidara, a polyandrous tradition unique to the local Hatti tribe wherein a woman marries multiple brothers to keep the household united and family land from splitting.

After videos of the wedding showing him standing alongside his brother and their bride during the ceremony, Pradeep, a government worker, gave media interviews expressing pride in the cultural roots of their decision. “We followed the tradition publicly as we are proud of it and it was a joint decision,” he told the Press Trust of India.

Kapil, the younger sibling who works abroad, added: “We are ensuring support, stability and love for our wife as a united family. We’ve always believed in transparency.”

Sunita, originally from Kunhat village in the same district, wanted to make it clear she was not coerced into the arrangement. “I was aware of the tradition and made my decision without any pressure,” she told the Hindustan Times.

By the time The Independent reached the family at their home, their door was closed to the media. “This is our tradition. It is a part of our culture. I do not understand why everyone is interested in a private matter,” Pradeep said briefly, declining to speak further.

The wedding may have elicited viral interest on social media but local villagers say such unions are far from unusual in this remote area tucked away between high mountain ridges and sharp valleys.

“It is an age-old tradition, going back to the time people first settled in this part,” Shillai resident Raghuvir Tomar, 55, says, sitting in a small sweet shop overlooking the Himalayas. “There were no roads, no transport. The nearest town was 70km away. Scarcity shaped everything – how we married, how we lived.”

In India, families with married sons often live together in the same house. Though the law gives daughters the right to ancestral property, custom means it is usually the sons who inherit it. There is thus always the fear that more couples in the family would mean more property disputes among brothers.

Here in Shillai, with its mountainous terrain, ancestral land is limited and vital. And for some residents, Jodidara offers a pragmatic solution.

“If brothers marry the same woman, there’s no question of splitting farmland. The family stays united, the land stays intact,” Tomar explains. “Sometimes it’s not just two – four or five brothers may marry the same woman.”

Locals say the practice traces its roots to the Hindu epic Mahabharata, in which Draupadi, the daughter of the king of Panchala, married five brothers, referred to as the Pandavas.

The Hatti community – consisting of approximately 300,000 people living in around 400 villages in the Sirmaur district in Himachal Pradesh and in Jaunsar Bawar in the neighbouring state of Uttarakhand – consider themselves the descendants of the Pandavas. This gives the custom the others names by which it is referred – Draupadi Vivah, loosely translating to Draupadi’s marriage or Pandav Pratha, the practice among Pandavas.

Tomar has first-hand experience of Jodidara not through his own marriage, but through his parents. “My father was in such a marriage. I had one mother and two fathers. We called them elder dad and younger dad. There was no concept of a biological father – just one united family,” he says.

He didn’t follow the tradition himself only because of timing, he says. “I married earlier. My younger brother was still studying, and he married later. Otherwise, maybe we would’ve done the same.”

He estimates that 30 to 40 households in Shillai still practise it. “This couple went viral because of social media. But for us, it’s not news.”

Sunita’s insistence that she consented to the marriage with both Pradeep and Kapil speaks to an uncomfortable aspect of Jodidara arrangements – that, like with many traditional weddings across the country, a certain degree of family pressure is often involved.

At a gathering of mostly male members of the community at a tea shop in Shillai, people here were reluctant to talk about the potential pitfalls of Jodidara marriages.

But away from the crowd, and speaking on condition of anonymity, a woman in her sixties tells The Independent how she came to be married to two brothers against her wishes.

“My husband has six more brothers. I was married to only one person,” she recalls. “But when I came here after the marriage, there were discussions – do we really need seven daughters-in-law for seven sons? And if that happens then the home will be divided into seven parts. So I was told, your husband is one person only but you have to take in another brother. Otherwise, the property would be divided.”

She said that while she had wed one man, she was “compelled to take another” and told to “take care of the brother as well” – a euphemism for sex.

“Child, this is what it was like earlier – you were forced and did not have much choice. We were told to either follow the norm or leave and return home. I am not literate, so I had to do as I was told,” she said, before clarifying: “No, no – not forced. Just pressured.”

Her own parents, she said, accepted the arrangement without question. But she expressed puzzlement over younger women still entering into Jodidara marriages. “The practice is in decline. And the girl [Sunita], unlike us, is educated. So what was the pressure for her?”

Asked about any other challenges she faced, the woman was reluctant to elaborate. “Let it go. It has been a while. I am old now. There are a lot of problems. The responsibility of two husbands is a lot. You should keep one husband happy or another? Then you have to look after them.”

In her youth, she was one of four wives shared among seven brothers. Such arrangements, while fewer today, still dot the region’s villages, both in Shillai and in the village of Kota Kwanu across the state border in Uttarakhand.

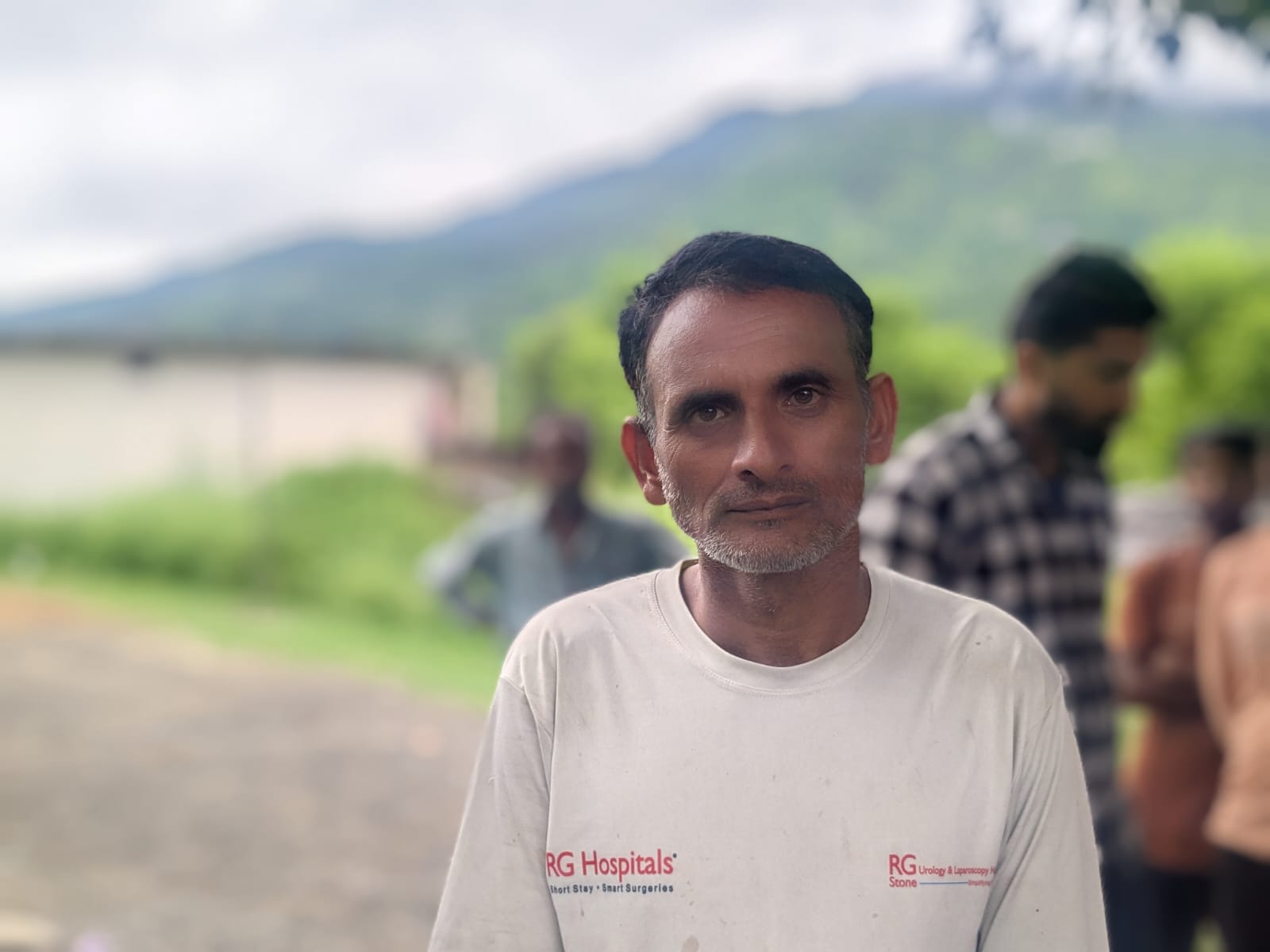

There, 62-year-old farmer Munna Singh Chauhan tells The Independent he was set up in a marriage with his wife and younger brother before he could even remember.

“I got married when I was a child – maybe two or three years old,” he said. “Earlier, elders would fix relationships before a child was even born, [saying]: ‘If you have a girl, she would be our daughter-in-law’.”

By the time his wife moved in, his brother hadn’t even been born. “It was decided beforehand – if I have a younger brother, we would be under Jodidara. One brother does the farming, another grazes goats, another takes care of cows. That’s why it is practised.”

Susheel Tomar, 33, lives with his wife and not one but two of his brothers who are also married to her.

“In fact, it’s quite normal here,” he says. “In some homes, there are three, four, even six or seven brothers sharing a wife. Even government officers follow this tradition.”

A professional driver, Tomar says the system works because it is built on understanding, and has plenty of practical benefits. “I work outside and come home every few months. When I’m here, the others go away to the fields or take care of business. When they’re here, I go to work. It’s all understood. No fights.”

Asked how intimacy is managed, he answers plainly: “There’s an understanding and it’s never a topic of dispute. When I come home, the others give me space. When they come back, I do the same.”

Another villager explains that brothers will keep a cap outside the bedroom when spending time with their wife, a signal to the other husband or husbands that they should not be disturbed.

Under Jodidara, there is no concept of a child having a single biological father. “We assign each child to a father for official records,” Tomar says. “But all are treated equally. Kids might call us ‘driver father’ or ‘doctor father’ depending on our profession. But they know we’re all their dads.”

Chauhan sees value in the system. “Now no one looks after the farmland – they leave with their wife. Under this practice, if one brother dies, another will take care of the wife and children. Our elders had foresight.”

Yet despite his conviction, he married his own children off separately. “One son is a teacher, one is in a bank, one has done BA. How will they manage together? Earlier, we were not educated. We walked miles to school, and most of us worked on farms that depended on rain. If the land is divided now, what’s left?”

Most men refused to countenance the idea of another potential issue with a Jodidara marriage, particularly an arranged one where the parties involved don’t know each other well beforehand. What happens if the bride ends up falling in love with only one groom, or expressing a strong preference for one brother over the other?

“If she does, then it won’t work,” says Tomar. “Jodidara only works if all are equally in it. A brother can’t say, ‘I want her for myself.’ Nor can the wife pick favourites. Everyone must consent.”

Chauhan insists any such disputes can be resolved without courts or divorce settlments. “If there’s a fight among brothers, we go to our god of justice, take vows, and that brings wisdom. That’s how it works here.”

But Kalyan Singh Negi, a lifelong resident of Shillai, says something like this happened when his Jodidara marriage did not work out.

“I had a Jodidara earlier, with my brother,” he said. “But it broke down, and I married again.”

When asked what caused the separation, Negi says: “Just because of love only,” without elaborating. “But the other marriage is also Jodidara. As in, we brothers share the new wife also. In the new wedding, we have no issues sharing the new wife. There is no difference.”

In Negi’s household, the shared arrangement includes seven children between the two brothers.

“The children belong to both of us. It doesn’t mean the kids call me or him uncle. We’re both fathers. That’s how it works here.

“It’s part of our system,” he says. “When we talk to the bride’s family, it’s understood that she’ll be the wife of both brothers. Nobody finds it offensive.”

Kundan Singh Shastri, general secretary of the Kendriya Hatti Samiti or local council, tells the Press Trust of India that Jodidara was “invented thousands of years ago to save a family’s agricultural land from further division.”

More men in a joint family meant better security, more hands for work, and fewer internal conflicts. And while the custom is not linked to caste and cuts across the social spectrum, it is gradually fading in the face of modernity – shrinking landholdings, urban migration, education, and individualism.

Village elders believe it works, and will continue to do so as long as there are enough willing participants advocating for the practice to be carried on. “These days love in society is reducing. People are getting educated, marrying separately, moving to cities, and leaving their land and people behind,” a villager in Kota Kwanu says.

“We urge you to spread this practice of polyandry – it keeps love among brothers and families.”