The number of whales and dolphins getting stranded on the Scottish coastline has increased at an exponential rate over the last 30 years, a new study warns.

The study, published in the journal Scientific Reports, marks the first time scientists have been able to quantify the scale of the increase in marine strandings around Scotland’s coastline.

In such events, a marine mammal is usually found dead on a beach, or is alive on land or in shallow water but unable to return to its ocean habitat.

Researchers from the University of Glasgow looked at all marine mammal species seen in Scottish waters, including baleen whales, short-beaked common dolphins, harbour porpoises and pelagic dolphins.

They used a 30-year dataset collected by the Scottish Marine Animal Stranding Scheme (SMASS) between 1992 and 2022 to examine the distribution and trends in marine mammal strandings.

Overall, 5,147 marine mammals were included in the study, having stranded in Scotland between 1992 and 2022.

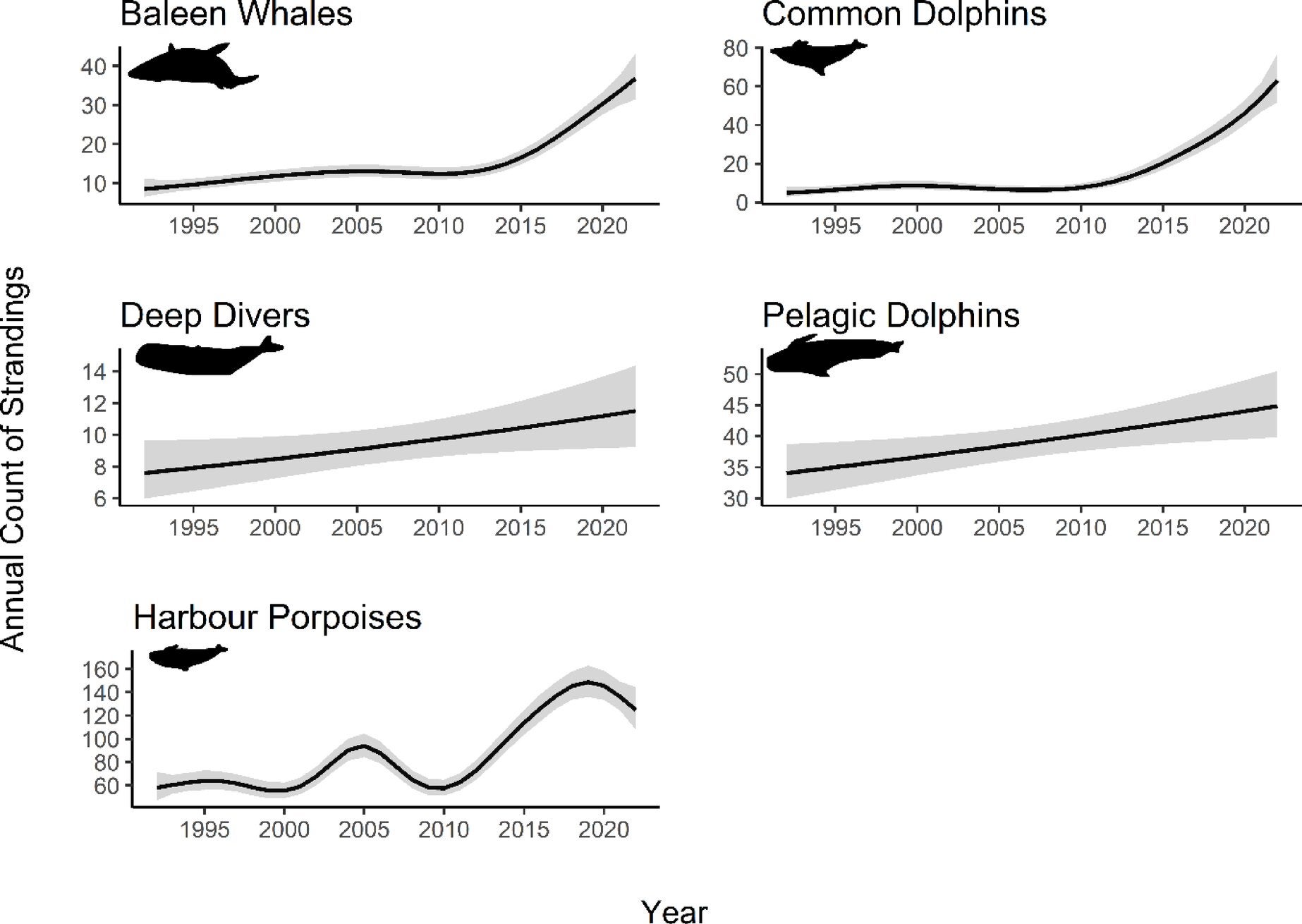

Scientists observed increasing rates across all such species, with some showing steep increases in their strandings.

Common dolphins and baleen whales particularly showed an “exponential increase” in strandings, suggesting these species are facing unprecedented pressures in Scottish waters, researchers said, warning that the scale and consistency of the rise indicates a “genuine cause for concern”.

They found that the stranding rates of these two species remained consistently low during the first two decades of the study, but rose sharply from 2010.

Researchers also found a disproportionate rise in strandings among juveniles of both species, indicating that younger animals could be particularly vulnerable.

Based on these findings, marine experts call for prioritising conservation efforts of common dolphins and baleen whales.

“By identifying where and when species are most at risk, we can target monitoring and conservation efforts at the critical times and locations needed to best safeguard the health of these ecosystems,” said Andrew Brownlow, Director of the SMASS.

In the research, harbour porpoises accounted for more than half of all the strandings, followed by pelagic dolphins at 24 per cent, common dolphins (10 per cent), and baleen whales (9 per cent).

Overall, there were no sex differences spotted in the annual stranding rates, but there were distinct seasonal trends observed for each group.

Such events were widespread across Scotland, but strandings of different species were clustered in certain areas.

Almost all species strand on the northwest coast, with porpoises predominantly stranding along the east coast around the Inner Moray Firth, the Outer Moray Firth and the Forth and Tay, and the southeast in the Clyde, according to the study.

“These animals act as sentinels of the ocean, and rising numbers of strandings may be an early warning that something is changing in the marine environment,” Dr Brownlow said.

“While some of the findings raise important concerns, the study also highlights that different regions face unique threats, each requiring tailored mitigation strategies,” he added.