There are Aussie actors so enveloped in British and American pop culture that you might need to be reminded that they’re from the land Down Under. These are your “secret Australians”, your Margot Robbies and Rose Byrnes or your Jacob Elordis. Eric Bana, the strong-of-jaw star of Troy, Munich, and Ang Lee’s Hulk, is not a secret Australian. His accent is thick. His skin is sun-kissed. His surname sounds as if it needs to be shouted, rowdily, across the length of a busy pub. “Oy, Baa-naa!” some Crocodile Hunter-type might blare. So it feels wrong to find him sitting in a checked button-up shirt in a New York office, where he’s been promoting his new Netflix drama, rather than on a beach somewhere in Melbourne, feet up, tinnie in hand, boasting about his remarkable sense of chill.

“I’m really good at not working,” the 56-year-old jokes. “It’s never felt like a big risk to say no to things. I’ve never panicked about work. It’s just not how I operate.”

Fire up the barbie, Bana’s here.

There was a period, nearly 25 years ago now, where Bana was positioned for a kind of stardom that he never found particularly appealing. “He has the face and musculature of the ideal action-oriented leading man,” went Vanity Fair back then. “But Bana has taken a tougher route.” After putting on two stone of weight to play the notorious Aussie criminal Mark Read in 2000’s Chopper, then losing it to reveal a sculpted face and physique that Hollywood could hardly say no to, Bana went rogue. Yes, he played to “romantic pin-up” type in The Time Traveler’s Wife, but otherwise he gravitated towards prickly, difficult anti-heroes. He stayed rooted in Melbourne with his partner Rebecca, whom he married in 1997, and their two children, and in 2003 played the angriest, greenest of the Marvel superheroes in the most dour of the Marvel superhero movies. Then he played a Mossad agent for Steven Spielberg in Munich (2005), before donning prosthetics to nefarious effect in JJ Abrams’ Star Trek. He dug it all so much more than the easy stuff.

“I’m very happy to die, you know? I’m happy to be killed off in something,” he tells me. “I’m happy to support [other actors] – it’s just more interesting. I don’t want the audience to see me and think he’s going to be the main guy until the end credits roll.”

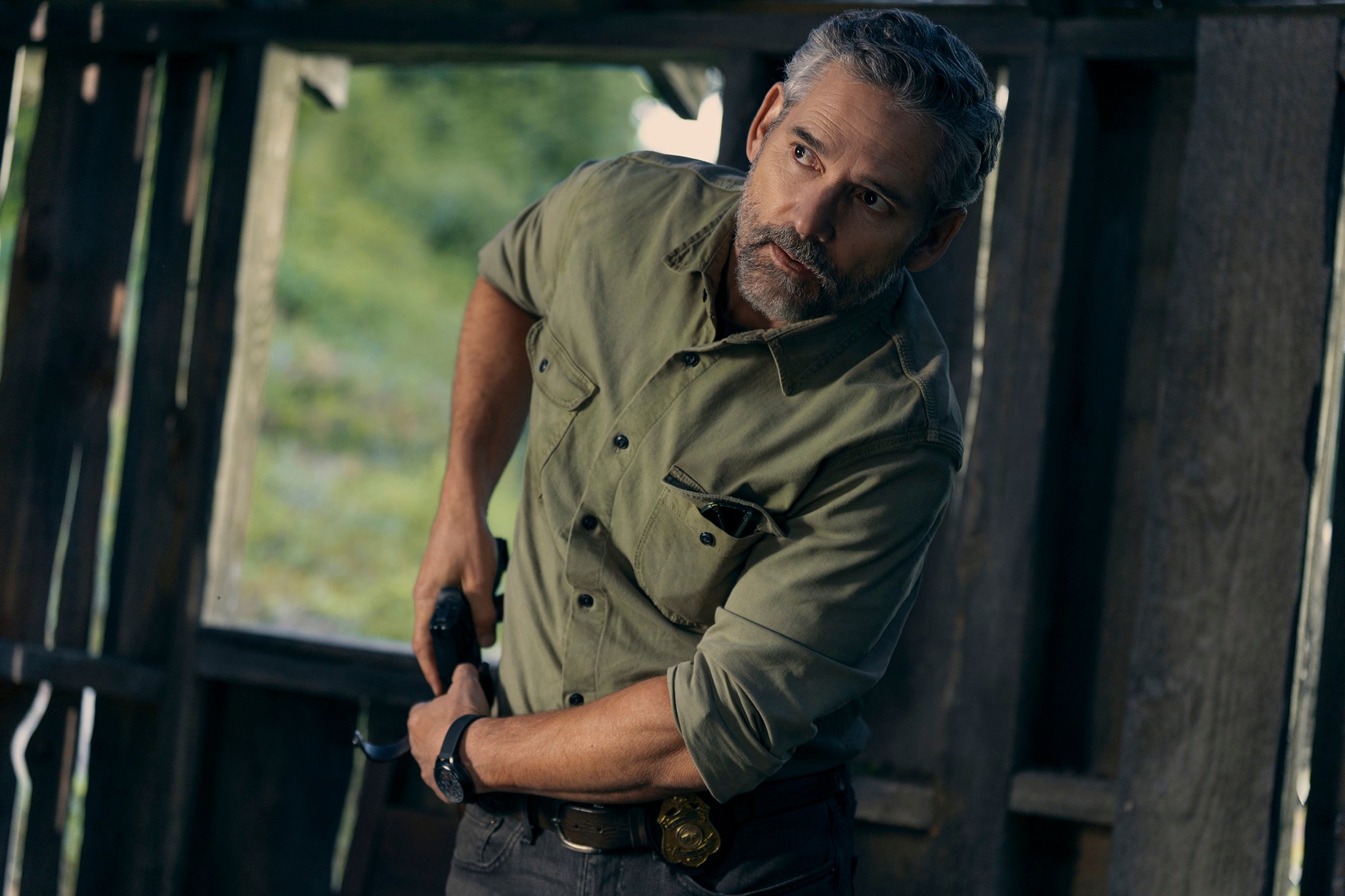

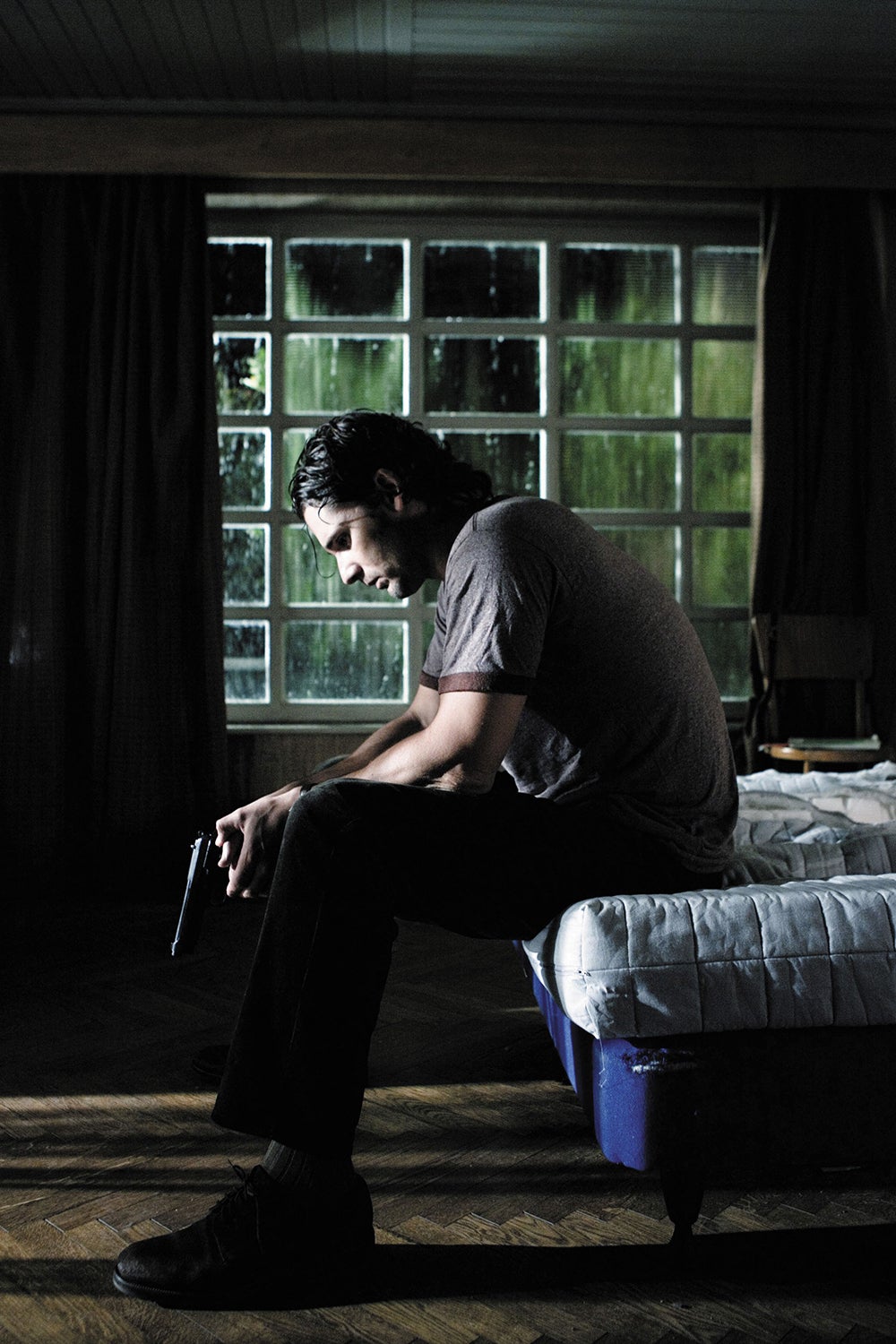

And I suppose that lends an additional air of intrigue to Untamed, Bana’s new Netflix series. It’s a mystery set in Yosemite national park in California, with Bana playing a taciturn parkland agent tasked with solving the murder of a young woman thrown off a clifftop. In less elegant parlance, Bana’s Kyle Turner is a bit of a moody git – brusque, mean, thoughtless, admired by his colleagues for his crime-solving acumen but not for his people skills. He’s no hero, so naturally Bana found him appealing.

“It’s not often that your lead character is allowed to get away with being so uncharming,” he says. “And we got to lean into the gruffness, the darkness and the uncomfortable [areas].”

There is, of course, a bit of levity here and there – mainly whenever Sam Neill appears as a senior park ranger who’s seemingly the only person able to crack Turner’s tough exterior. Somewhat inexplicably, Neill and Bana – two of the most successful exports from New Zealand and Australia, respectively – had never met before Untamed.

“I really felt like I knew Sam, and Sam felt like he knew me,” he remembers. “But we’d not only never met, we’d never even been at the same function together – just nothing. Never been anywhere near each other.” They bonded over wine. “And now hopefully we’ll go back to never seeing each other again,” he jokes. “Hang on, this is in writing, isn’t it?”

Before speaking to Bana, I found an old quote from the television writer Alexandra Cunningham, who cast him as a seductive sociopath in her limited series Dirty John in 2018. She spoke about being desperate to work with him, but that she’d been told that he’d “historically had parameters for how a project needed to be set up”. It intrigued me. How hard really is it to get Bana to commit to a project?

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 day

New subscribers only. £8.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled.

Try for free

ADVERTISEMENT. If you sign up to this service we will earn commission. This revenue helps to fund journalism across The Independent.

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 day

New subscribers only. £8.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled.

Try for free

ADVERTISEMENT. If you sign up to this service we will earn commission. This revenue helps to fund journalism across The Independent.

“It doesn’t come from a place of arrogance,” he explains now. “You just have to be brutally honest about the quality of your material. If something has potential but it’s not there yet, let’s not be shy about talking about it. No single actor, writer or director is so good that they can overcome scripts that aren’t good. I don’t care who’s involved. Some people can elevate things a little bit, but once you’re underwater, you’re underwater.”

Naturally, my mind jumps to Hulk. Production on the movie was a famously tortured affair, with filmmaker Ang Lee – an undeniable genius, if ill-suited for comic book films – sometimes demanding hundreds of takes of scenes. Bana struggled. “Humour and irony were not welcome on the set,” he once told GQ. The film drew mixed reviews and didn’t make enough money to warrant a sequel – a failed reboot was made in 2008 with Edward Norton, and Mark Ruffalo’s Hulk has only ever been a supporting player in Marvel films since.

“We didn’t have a finished script,” Bana remembers. “I came on board [the film] based only on elements. And it was early in my career, so I wasn’t in the position I’m in now where I can [ask for changes].”

He thinks his approach to scripts stems from his comedy background. Before Chopper placed Bana on the international stage, he was famous in Australia as a stand-up comedian, appearing for years on Full Frontal – an Aussie spin on America’s Saturday Night Live – and then his own sketch show, Eric. “When you’re writing, if an idea doesn’t fly in the room with other writers and we’re not laughing, you can’t expect the audience to make the joke better. So you have to be forensic about it – working in comedy always felt like being an X-ray machine, you know?”

One film he knew was great on the page was Munich, which has taken on a very different life since the events of 7 October. Spielberg’s movie cast Bana as the leader of a team of Mossad agents ordered to assassinate 11 Palestinians involved in the massacre of Israeli athletes at the 1972 Munich Olympics. It was beset by controversy upon release, with Spielberg accused from different parties of being anti-Israeli, anti-Palestinian, or for gesturing towards moral similarities between the most zealous of both states. But the film’s reputation has improved in the years since, with critic Lisa Schwarzbaum writing in The New York Times in 2023 that it “reverberates with deep meaning and gravitas” and is “the best movie about Israel and Gaza” that has ever been made.

“Someone sent me that article, which was a lovely thing to get,” Bana says. “But I felt like the film was on a slow burn ever since it was released. It was so politicised when it came out. It was almost like people used the film as an opportunity to talk about how much they knew about the region – they were never talking about the film, the script, the performances, or any of the technicality involved.

“But over time, people have just seen the film as the film, and it’s always been one that I get people come up and talk to me about, who’ve discovered it years later. It’s, I think, a film that has aged really well. Tony Kushner’s writing is incredible, and the language is kind of timeless in terms of what it says about revenge and the region and the politics of it all. So I’m not that surprised [about its legacy].”

I ask if he’d likely be cast in Munich if it were made today, as he’s not Jewish himself. He shrugs. “I dunno, mate, I’ve never really thought about it,” he says. But he thinks Munich itself probably wouldn’t be made today – not because of its subject matter, but more because most of the films that Bana made back then (among them Judd Apatow’s brilliant Funny People, or the gambling drama Lucky You) would struggle to find backing in 2025. “Would there be budget for it? Would those films be considered commercial? I don’t know.”

He’s not a total cynic when it comes to modern filmmaking, though. “You’re constantly told that they don’t make comedies or dramas anymore, but I just don’t listen to it,” he says. “I’m sure there are some young actors who’ve been told over the last 10/15 years that it’s just the Marvel Universe and nothing else for you, but I completely disagree with it.”

He points to Saoirse Ronan, with whom he worked on the cult action movie Hanna when the now four-time Oscar nominee was just 16 years old. “Just look at the career that she’s carved out for herself,” he says. “I’ve loved watching her progress, because I’ve seen her manoeuvre the industry in a similar manner to what I did – in the sense that I’m not going to go on someone else’s ride, I’m going to do what I want.”

He knows it takes bravery, though.

“You have to be really determined, but at the same time, I believe that if you’re patient enough, you will find another great drama, another great film. It’s harder now, but it’s still possible.”

Spoken with the relentless chill of a true-blue beach bum.

‘Untamed’ is streaming on Netflix