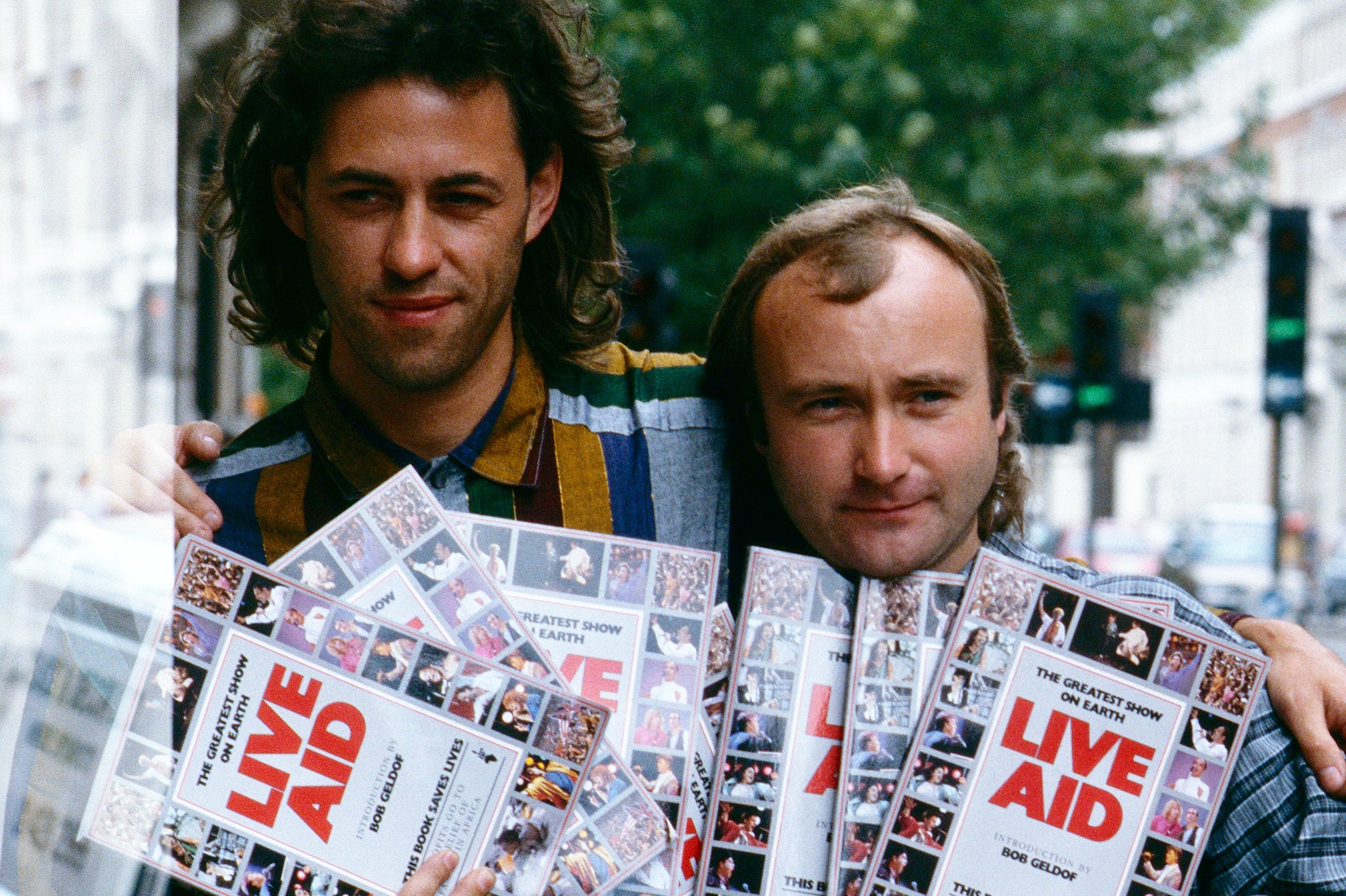

Forty years ago this weekend, two concurrent concerts were held in London and Philadelphia in aid of relieving a brutal famine that had taken hold of Ethiopia. The legend of Live Aid has grown exponentially ever since. But each retelling draws upon the same familiar names and faces, the cameras trained on the contemporary darlings of Geldof and Collins, Freddie and Diana.

The many millions who watched on from home are treated as a matter of scale, not depth. They are remembered as an amorphous blob of common opinion, a simplified version of the public that in reality can never exist. And yet four decades from the event itself, each individual person retains their own individual memory, full of colour and life and utterly unique to themselves.

Peter Collins was one of the lucky ones. He grew up in Belfast, playing in bands and exploring the punk scene, a devoted reader of Melody Maker and the NME. Early in the morning on 13 July 1985, he and his schoolmate Alan headed for Belfast City Airport, bound for Heathrow, then London and Wembley. Already, he had a hunch that it was a day that he’d be talking about for years to come.

Forty years later, he still remembers almost every detail. There was the young boy in the crowd who waited all day for David Bowie, only to suffer an epileptic fit at the very moment he took to the stage; the people with picnic blankets and baskets; the tray of room service sandwiches delivered up to their hotel room later that night. In fact, the only thing missing from Peter’s memory is the music.

“We were going to it not because of how good the bands would be,” he explains. “We were going to it because it felt like that was going to be the thing that was happening on that day, the thing that everybody in the world was going to be aware of.”

Paul Rance was 25. He watched Live Aid from a sleepy village in the depths of rural Lincolnshire and describes it as one of the greatest days of his youth. “For people who were a bit older than me, it would have been a bit like seeing England win the World Cup,” he says. “A big communal event. It felt like Woodstock to me.”

Joanne Ash was only nine. Sometimes she is unsure of which parts of the day really happened and which parts have been backfilled into a kind of false memory. Certainly, she recalls having been at a birthday party, the television blaring all day long inside the house as the guests filtered in sporadically from the outdoor sunshine. The party was in Feltham, a town on the western outskirts of London, less than 15 miles from Wembley Stadium.

“I’m convinced that we could hear it,” says Joanne. “I’ve got this idea that we were in the garden going – did you hear that?! I’m sure it was round about the Queen performance. It was just a roar.” At just nine, she stood within earshot of the centre of the universe.

Eighteen-year-old Simon Moffatt could hardly have been further away. He and his friends were on a holiday, walking between youth hostels in southwest Wales, with two of the group celebrating their birthdays. “It was quite a big week for us, really. We would have just finished our A-levels. You get to that age and your whole friendship group starts to disband.

“One of our group had brought a little transistor radio with them. We arrived at this little bay, this tiny little bay in southwest Wales, and put this transistor radio on, listening to Status Quo [opening the concert with] ‘Rockin’ All Over the World’. It was a beautiful sunny day, sitting at the end of the jetty, and then we realised – ‘Ah, we don’t really want to listen to Status Quo, do we?’ And so after that song we put the radio away and got out the birthday cake. That was lovely.”

Keith Webb travelled from Grimsby for the concert. He’d been to big gigs before, but this one felt different. “I wasn’t there for an audiophile experience,” he says. “Everybody knew what they were there for. I think there was a huge element of looking at the pictures [of famine] coming out at the time and just realising that we had to do something. The excitement was generated by the fact that we were going to do something to help. The entire concert sold out before a single artist was announced to play.”

“Back in the day we had about four channels,” remembers Alison Knight, who watched the concert at home with her older brother. “If your parents were watching the news, then you had to watch the news too.” Michael Buerk’s footage of the famine flooded into every home in Britain.

“To be honest, I still can’t watch it,” says Paul. “It’s so horrific when you know what’s coming. It was on the BBC news, it was a headline story, [and] there’s a lot of people who were moved by it. You’d have to have a heart of stone not to be.”

“There was no Comic Relief at that point, there wasn’t Children in Need,” remembers Joanne. Fundraising on such a scale was almost revolutionary. What started with Band Aid in the Christmas of 1984 reached a fever pitch by the following summer and soon enough Live Aid became a story in and of itself.

“It was blanket coverage,” says Alison. “I remember hearing about the television link up to America, and obviously Phil Collins [flying between the two concerts] on the Concorde was a big thing too. You did get a sense that nobody really knew if it was going to work.”

But not everybody was so enamoured with the concert. “We were the real sort of NME-reading indie kids. None of our favourite bands were allowed anywhere near Live Aid,” says Simon. “We were very taken with the whole charity aspect, but it was just that the whole lead-up to it almost looked cheesy. They kept going on and on about how Phil Collins was going to play twice, how he was going to fly to America on the Concorde. I was just about to go to Sheffield Poly and try to dress like The Jesus and Mary Chain. The idea of seeing Phil Collins play twice was not something I was very excited about!”

“It goes to show how all-pervasive it was. There we were, probably as far away from it as you can be in the UK. But even now, in our little group chat, all four of us said that’s one of the most memorable moments of our whole lives, sitting on the end of that little jetty. Even when you tried to ignore it, it becomes a touchstone for your whole life, and that’s quite a thing.”

Paula Atkinson caught a National Express coach down from Liverpool, aged 19. She remembers watching Paul McCartney close the day’s festivities with “Let It Be”. “When the chorus started, everyone was up on their seats, jumping up and down. I stood still for a minute – and I carried on going up about four inches in the air with the force of everyone jumping.”

“I was laughing, I was going, ‘Look! Watch me, watch me!’ That’s when you realised, at the end, the power of all the people inside [the stadium]. Physically and mentally, the power of all the people all together.”

The most remarkable thing about Live Aid in a modern context is not the music, nor the fundraising, nor the legacy. Instead, it is the central achievement of convincing such an enormous number of people to care about one single issue – the famine in Ethiopia. People truly believed that they could make a difference. “You saw the enthusiasm and the fire coming out of Bob Geldof and how sure he was that we could come together and get this money, that we were going to make a real difference,” says Joanne.

Sam Richards watched the concert aged 11 in her neighbours’ back garden, with their boxy television wheeled outdoors into the afternoon sun. “My parents were baby boomers who were born just after the war,” she says. “My sense was that the war loomed large in our childhoods and nuclear war loomed large in the Eighties. But it seemed like everything was moving forwards and that society was going to get better, you know? I remember thinking that we can make a difference and we can stop these awful things.

“Well, I’m 51 now, and those things haven’t stopped, and even worse things have come along. I still have hope that it will change, just the last few years have changed everything so quickly that it’s difficult to hold onto it.”

“We’re in a bad moment, no doubt about it,” says Paul. “These are the worst times since, well, people would say since the Cold War – but I’d say in my lifetime, really. We had a lot of problems in the Eighties, but we had a lot of hope despite everything. Whether there’s that same hope these days, I’m not so sure. Everybody wants days of hope, don’t they?”

“I was inspired for years,” says Sam. “I read Bob Geldof’s autobiography, I still contribute and raise money and things for charities. When the [Queen biopic] Bohemian Rhapsody came out, I went back and rewound the concert about three times. Things like that do still move me to tears. It’s a strong feeling.”

“I don’t feel tinged with cynicism at all. It was brilliant.”

.png?trim=304,0,362,0&width=1200&height=800&crop=1200:800)