In 2015, two members of the Blue Beach Fossil Museum in Nova Scotia found a long, curved fossil jaw, bristling with teeth. Sonja Wood, the museum’s owner, and Chris Mansky, the museum’s curator, found the fossil in a creek after Wood had a hunch.

The fossil they found belonged to a fish that had died 350 million years ago, its bony husk spanning nearly a metre on the lake bed. The large fish had lived in waters thick with rival fish, including giants several times its size. It had hooked teeth at the tip of its long jaw that it would use to trap elusive prey and fangs at the back to pierce it and break it down to eat.

For the last eight years, I have been part of a team under the lead of palaeontologist Jason Anderson, who has spent decades researching the Blue Beach area of Nova Scotia, northwest of Halifax, in collaboration with Mansky and other colleagues. Much of this work has been on the tetrapods — the group that includes the first vertebrates to move to land and all their descendants — but my research focuses on what Blue Beach fossils can tell us about how the modern vertebrate world formed.

Birth of the modern vertebrate world

The modern vertebrate world is defined by the dominance of three groups: the cartilaginous fishes or chondrichthyans (including sharks, rays and chimaeras), the lobe-finned fishes or sarcopterygians (including tetrapods and rare lungfishes and coelacanths), and the ray-finned fishes or actinopterygians (including everything from sturgeon to tuna). Only a few jawless fish round out the picture.

This basic grouping has remained remarkably consistent, at least for the last 350 million years.

Before then, the vertebrate world was a lot more crowded. In the ancient vertebrate world, during the Silurian Period (443.7-419.2 MA) for example, the ancestors of modern vertebrates swam alongside spiny pseudo-sharks (acanthodians), fishy sarcopterygians, placoderms and jawless fishes with bony shells.

Armoured jawless fishes had dwindled by the Late Devonian Period (419.2-358.9 MA), but the rest were still diverse. Actinopterygians were still restricted to a few species with similar body shapes.

By the immediately succeeding early Carboniferous times, everything had changed. The placoderms were gone, the number of species of fishy sarcopterygians and acanthodians had cratered, and actinopterygians and chondrichthyans were flourishing in their place.

The modern vertebrate world was born.

A sea change

Blue Beach has helped build our understanding of how this happened. Studies describing its tetrapods and actinopterygians have showed the persistence of Devonian-style forms in the Carboniferous Period.

Whereas the abrupt end-Devonian decline of the placoderms, acanthodians and fishy sarcopterygians can be explained by a mass extinction, it now appears that multiple types of actinopterygians and tetrapods survived to be preserved at Blue Beach. This makes a big difference to the overall story: Devonian-style tetrapods and actinopterygians survive and contribute to the evolution of these groups into the Carboniferous Period.

But significant questions remain for palaeontologists. One point of debate revolves around how actinopterygians diversified as the modern vertebrate world was born — whether they explored new ways of feeding or swimming first.

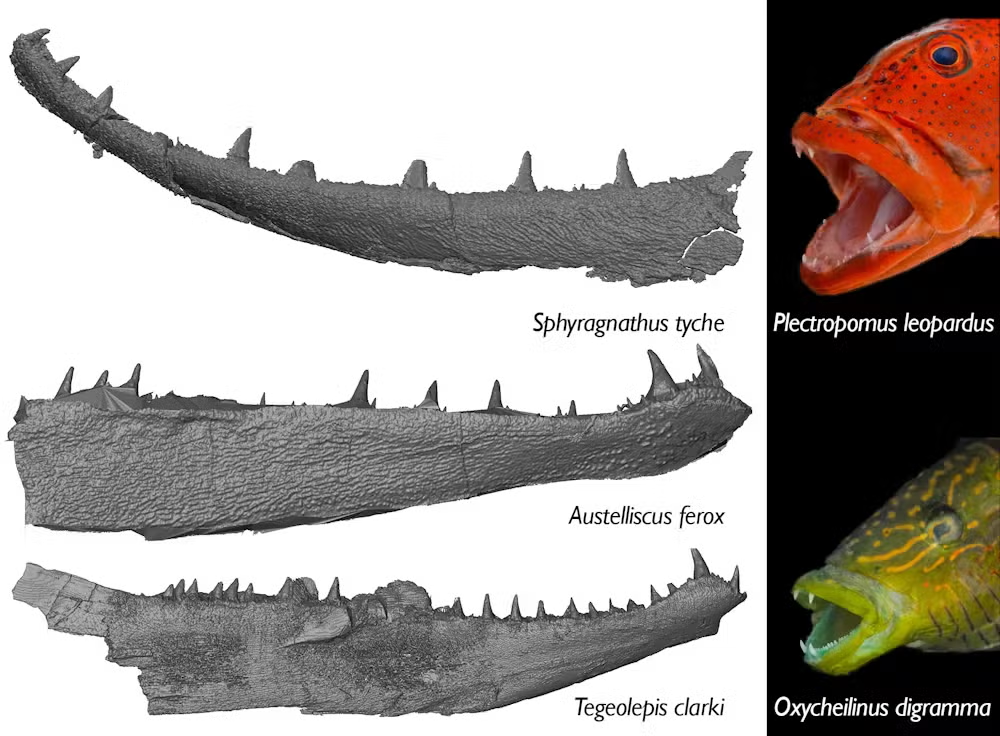

The Blue Beach fossil was actinopterygian, and we wondered what it could tell us about this issue. Comparison was difficult. Two actinopterygians with long jaws and large fangs were known from the preceding Devonian Period (Austelliscus ferox and Tegeolepis clarki), but the newly found jaw had more extreme curvature and the arrangement of its teeth. Its largest fangs are at the back of its jaw, but the largest fangs of Austelliscus and Tegeolepis are at the front.

These differences were significant enough that we created a new genus and species: Sphyragnathus tyche. And, in view of the debate on actinopterygian diversification, we made a prediction: that the differences in anatomy between Sphyragnathus and Devonian actinopterygians represented different adaptations for feeding.

Front fangs

To test this prediction, we compared Sphyragnathus, Austelliscus and Tegeolepis to living actinopterygians. In modern actinopterygians, the difference in anatomy reflects a difference in function: front-fangs capture prey with their front teeth and grip it with their back teeth, but back-fangs use their back teeth.

Since we couldn’t observe the fossil fish in action, we analysed the stress their teeth would experience if we applied force. The back teeth of Sphyragnathus handled force with low stress, making them suited for a role in piercing prey, but the back teeth of Austelliscus and Tegeolepis turned low forces into significantly higher stress, making them best suited for gripping.

We concluded that Sphyragnathus was the earliest actinopterygian adapted for breaking down prey by piercing, which also matches the broader predictions of the feeding-first hypothesis.

Substantial work remains — only the jaw of Sphyragnathus is preserved, so the “locomotion-first” hypothesis was untested. But this represents the challenge and promise of palaeontology: get enough tantalising glimpses into the past and you can begin to unfold a history.

As for the actinopterygians, current research indicates that they first diversified in the Devonian Period and shifted into new roles when the modern vertebrate world was born.

Conrad Daniel Mackenzie Wilson is a PhD candidate in Earth Sciences at Carleton University.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.