The world is on track to breach the 1.5C global warming threshold in the next three years, scientists have warned in a new international study.

If current emissions continue, humans will have released enough carbon dioxide by early 2028 to lock in 1.5C of long-term warming since preindustrial times, according to the study.

The 1.5C target set under the 2015 Paris Agreement is considered a critical limit beyond which climate impacts such as extreme heat, drought, storms and sea level rise could become far more dangerous, especially for the poorest and most vulnerable populations.

“Things aren’t just getting worse. They’re getting worse faster,” said Zeke Hausfather, study co-author from the tech firm Stripe and climate group Berkeley Earth.

“We’re actively moving in the wrong direction in a critical period of time that we would need to meet our most ambitious climate goals. Some reports, there’s a silver lining. I don’t think there really is one in this one.”

The annual Indicators of Global Climate Change report, published in Earth System Science Data, brings together research from almost 60 leading climate scientists. It notes that the remaining “carbon budget”, the amount of CO2 that can still be emitted while staying below 1.5C, has shrunk to just 143 billion tonnes.

At current emission rates of 46 billion tonnes per year, the limit will be reached in less than three years.

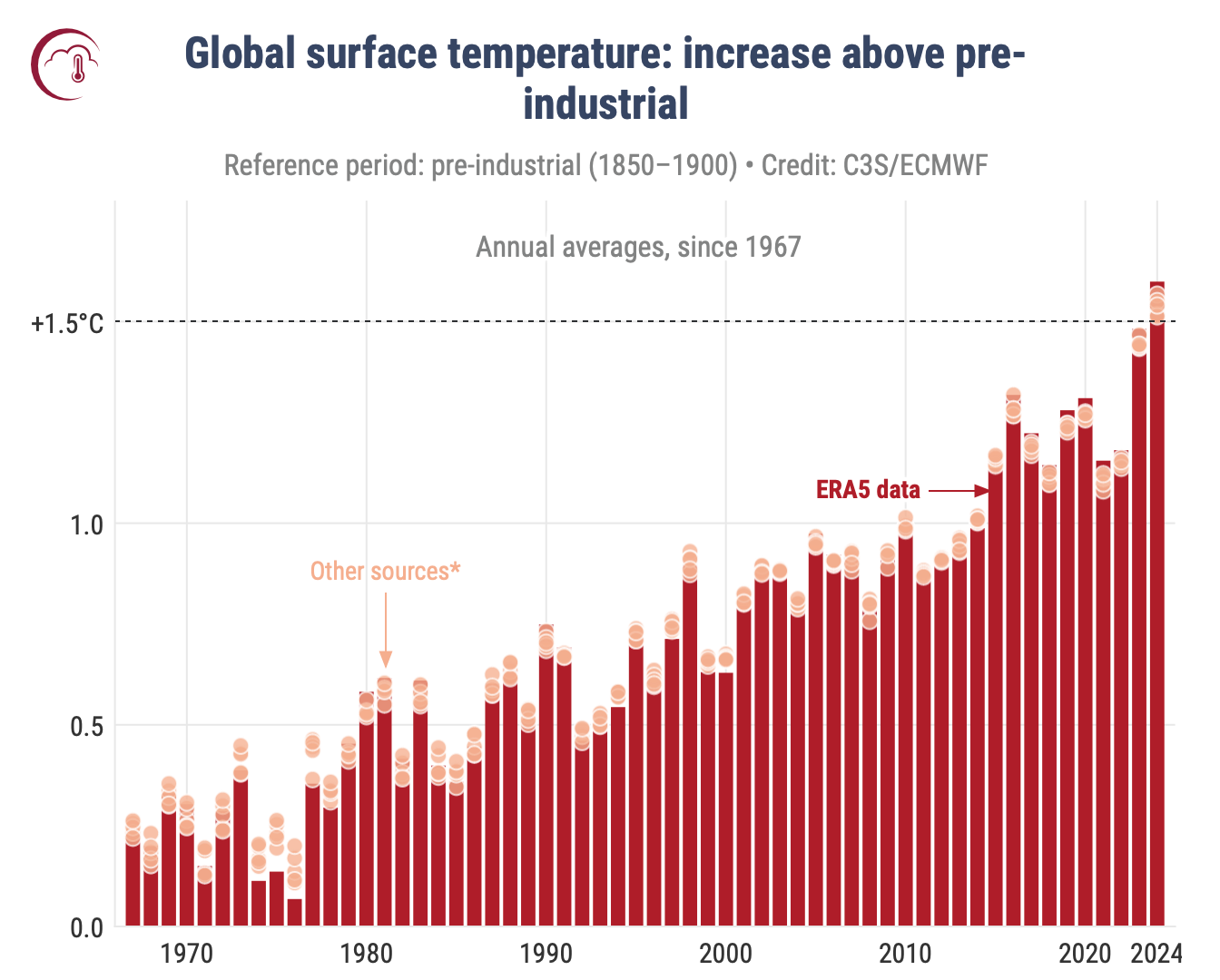

So far, global temperatures have risen by about 1.24C, the study points out. And for the first time ever, the planet passed the 1.5C mark for an entire year in 2024, though the Paris target refers to sustained long-term warming typically measured over two decades.

Scientists say without drastic emissions cuts, the world will be unable to prevent warming from surpassing the threshold, leading to a rise in extreme weather events and climate-related disasters and increasing the risk of triggering irreversible changes.

The report also warns the carbon budget for 1.6C or 1.7C could be exceeded within nine years, which will significantly intensify these impacts.

Long-term estimates show current average global temperatures to be 1.24C higher than in the pre-industrial age. “Under any course of action, there is a very high chance that we’ll reach and even exceed 1.5C and even higher levels of warming,” Prof Joeri Rogelj, research director at the Grantham Institute, said. “1.5C is an iconic level but we are currently already in crunch time…to avoid higher levels of warming with a decent likelihood or a prudent likelihood as well and that is true for 1.7C, but equally so for 1.8C if we want to have a high probability there.”

But Prof Rogelj added that reductions in emissions over the next decade could still “critically change” the rate of warming and limit the magnitude and the extent by which the world would exceed 1.5C.

“It’s really the difference between just cruising through 1.5C towards much higher levels of 2C or trying to limit warming somewhere in the range of 1.5,” he said.

Piers Forster, professor of climate physics at the University of Leeds who has helped author the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change reports, said the new study highlighted how climate policies and pace of climate action were “not keeping up with what’s needed to address the ever-growing impacts”.

In 2024, the best estimate of observed global surface temperature increase was 1.52C, of which 1.36C could be attributed to human activity, caused by global greenhouse gas emissions, the scientists said.

The latest study found last year’s high temperatures were “alarmingly unexceptional” as the combination of human-driven climate change and the El Nino weather phenomenon pushed global heat to record levels.

While global average temperatures exceeded 1.5C for the first time last year, this didn’t mean the world had breached the Paris agreement, which would require average global temperatures to exceed the threshold over multiple decades.

When analysing longer-term temperature change, the best estimates show that average global temperatures were 1.24C higher between 2015 and 2024 than in pre-industrial times, with 1.22C caused by human activities.

Elsewhere, the study noted that human activities were affecting the Earth’s energy balance, with the oceans storing about 91 per cent of the excess heat, driving detrimental changes in every component of the climate system such as sea level rise, ocean warming, ice loss, and permafrost thawing.

Between 2019 and 2024, mean sea level also increased by around 26mm, more than doubling the long-term rate of 1.8mm per year seen since the turn of the 20th century.

Dr Aimee Slangen, research leader at the NIOZ Royal Netherlands Institute for Sea Research, argued the rise was already having an “outsized impact” on low-lying coastal areas, causing more damaging storm surges and coastal erosion.

“The concerning part is that we know that sea-level rise in response to climate change is relatively slow, which means that we have already locked in further increases in the coming years and decades,” she said.

IPCC’s last assessment of the climate system, published in 2021, highlighted how climate change was leading to widespread adverse impacts on nature and people.

“Every small increase in warming matters, leading to more frequent, more intense weather extremes,” Professor Rogelj said.

“Emissions over the next decade will determine how soon and how fast 1.5C of warming is reached. They need to be swiftly reduced to meet the climate goals of the Paris Agreement.”