The complex life of Mark Twain, a writer dubbed “the Father of American Literature”, is told expertly in Pulitzer winner Ron Chernow’s comprehensive 1,100-word biography Mark Twain (Allen Lane). In the years preceding Twain’s death in 1910, at the age of 74, it becomes a deeply sorry tale indeed. The author of Adventures of Huckleberry Finn was a heavy drinker, plagued by bronchial coughs and itchy piles. He lambasted “the bastard human race” and dismissed his fellow citizens as “just tubs of rotten offal”. Chernow offers a balanced, insightful view of the whole Twain package and does not gloss over the celebrated author’s “college-girl habits”, Twain’s own phrase for the way he groomed young girls he creepily called his “angel fish”.

Two lighter reads, particularly for those with a taste for quirky travel books, are Ben Aitken’s witty Shitty Breaks: A Celebration of Unsung Cities (Icon Books), and Nigel Tassell’s charming Final Destination: Riding Britain’s Trains to the End of the Line (Mudlark), which offers a guide to 16 journeys (spanning from Wick in upper Scotland to Penzance in Cornwall). The accounts will make any fan of railways want to experience these delights for themselves.

A couple of recommended fiction books this month are Sarah Moss’s Ripeness (Picador), an impressive story of love and belonging, spanning 1960s Italy to contemporary Ireland, and Leo Robson’s engaging and smartly ironic debut The Boys (Riverrun), a generational saga set during the London Olympics of 2012.

My picks for novel, non-fiction book and biography of the month are reviewed in full below:

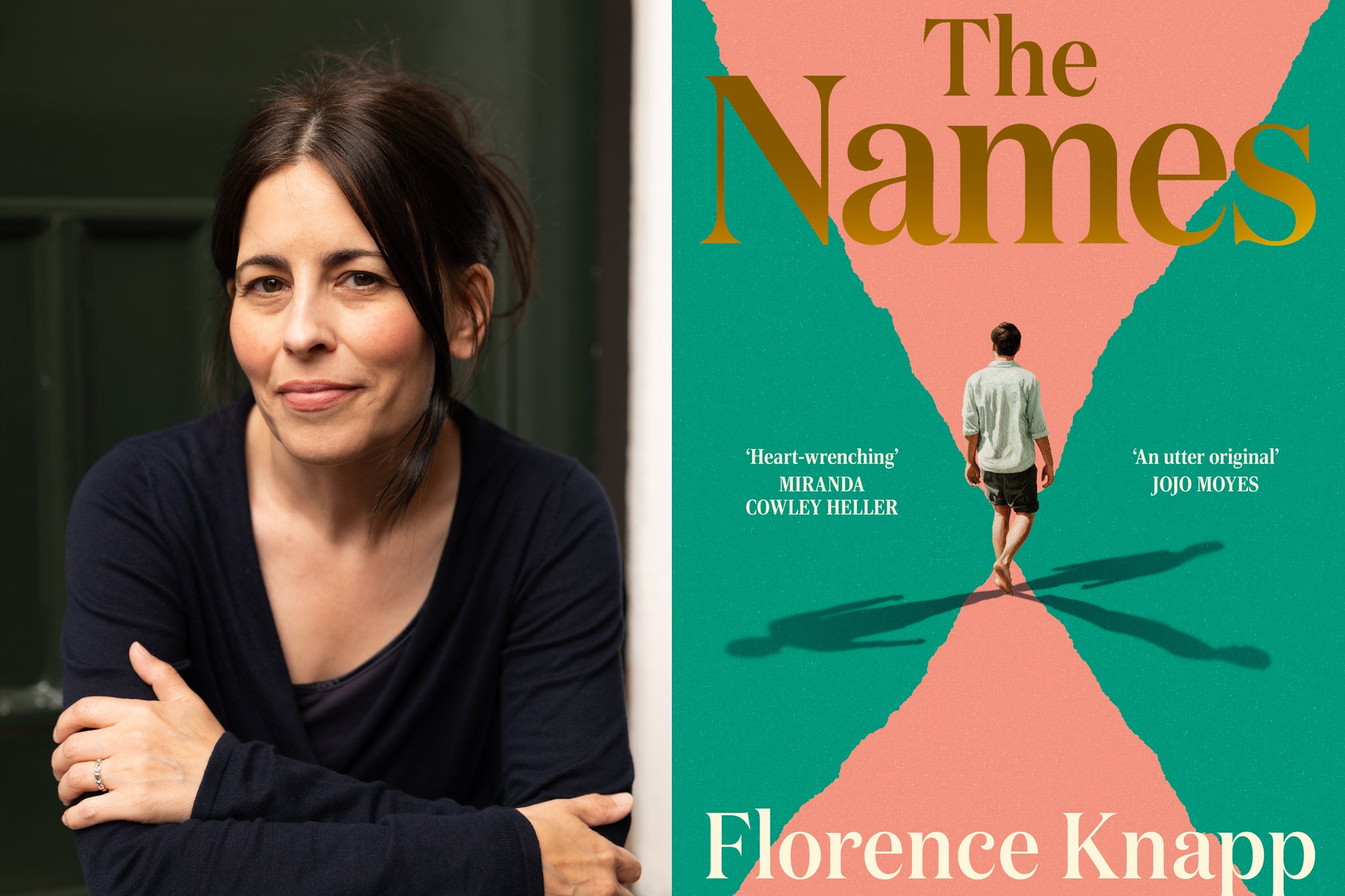

Novel of the month: The Names by Florence Knapp

★★★★★

The Names, in simple terms, is the story of three different versions of the same life, with a trio of wildly differing fates panning out from one simple decision: Cara’s choice of name for her newborn son.

Spanning 35 years, Florence Knapp’s superb debut novel shows what happens to the same boy whether he is Bear – a name chosen by his older sister Maia because it sounds “all soft and cuddly and kind” – or Julian, a talismanic name meaning “sky father”, or Gordon, a replica of his father’s name and one “that will tie him to generations of domineering men”.

Knapp breaks the action into six sections – 1987, 1994, 2001, 2008, 2015 and 2022, in a time frame echoing the famous Seven-Up television documentaries – and along with the varying scenarios for Bear, Julian and Gordon, we also see how the decision affects Cora herself, and Maia, and a whole cast of relatives, lovers, friends and strangers.

The central brother-sister relationship is depicted beautifully in each iteration. Another constant is the sharp portrait of Gordon senior, a controlling, abusive middle-class husband. Outwardly, he is a respectable GP, venerated by the local community, at home he is vile. One of Knapp’s strengths is etching not only a convincing portrait of a truly menacing man but also providing a subtle picture of how society fails to keep women safe from domestic abuse, both mental and physical. It’s a small quibble, I concede, but the exposition of the family origins of the doctor’s warped character was a touch heavy-handed.

Nevertheless, Knapp builds on her clever premise, and events unfold with a neat unpredictability. The three different life stories are told with imagination and cohesion, and the author also explores wider themes such as teenage misogyny, sexual identity and the power of true friendship. And Knapp, who previously wrote a non-fiction book about quilt-making, offers gorgeous descriptions of the skills and passions of the art-makers who weave in and out of the plots.

The Names is a thoroughly engrossing novel and a profound debut. The brutality and cruelty make it a difficult read at times, but Knapp’s tender touches rescue the reader from some of the pain.

‘The Names’ by Florence Knapp is published by Phoenix on 8 May, £16.99

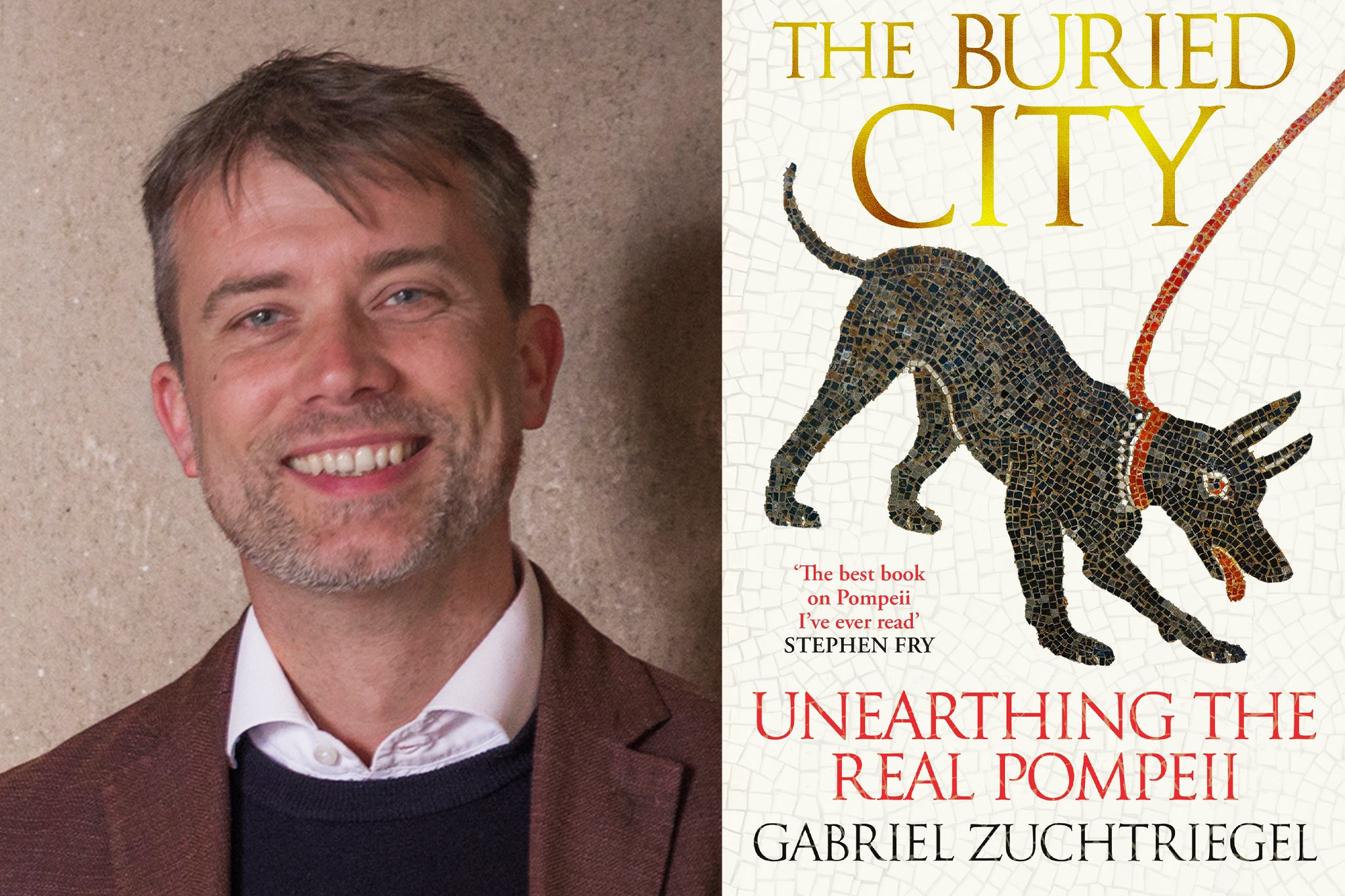

Non-fiction book of the month: The Buried City: Unearthing the Real Pompeii by Gabriel Zuchtriegel

★★★★☆

As I was reading The Buried City: Unearthing the Real Pompeii, the latest excavation of the city buried alive by the eruption of Vesuvius on 24 August 79 CE unearthed two remarkable long-lost sculptures, including one of a female priestess, which had been built into a wall of a necropolis near the main entrance gate into Pompeii. It really is a living story of the dead.

Gabriel Zuchtriegel, a German-born Italian citizen who is Director General of the Archaeological Park in Pompeii, has written an illuminating, engrossing guide to a world frozen in time. He is infectiously enthusiastic about his work, and the book – translated from the German by Jamie Bulloch – makes you yearn to visit and see friezes and architectural wonders for yourself.

Herman Melville said of Pompeii that it was “same old humanity”. If so, it was one brimming with sensuality and eroticism. “The modern distinction between homosexuality and heterosexuality was completely alien to the ancient world,” writes Zuchtriegel. “Nobody had to commit themselves to a specific sexual orientation.” He adds that women received a horrendous deal in ancient Pompeii. “Whether a woman gave her consent or not seemed simply irrelevant” in 79 CE; the author explains, and that sexual violence and rape were common. He asserts several times that the ancient world has relevant things to say to 21st-century people – so make of it what you will that the town’s brothel, the Lupanar, remains one of the most visited places by tourists.

If (like me) your knowledge of what happened at Pompeii consists of the disturbing illustrations in primary school picture books, you will find much that fascinates in The Buried City, including the vivid, scientific descriptions of what happens when a mountain top literally explodes in a volcanic eruption. Zuchtriegel flies off in lots of interesting directions – about petty academic behaviour, the misogyny faced by trailblazing female academics, the Elgin marbles, looting and the mafia’s part in the illegal trade in antiquities – right up to the way digital technology, AI and drones are helping modern archaeologists.

“Pompeii is like a rip in the screen through which we have the opportunity to take a peek behind the official version of history,” says Zuchtriegel, who is an enlightening guide to an amazing ancient show.

‘The Buried City: Unearthing the Real Pompeii’ by Gabriel Zuchtriegel is published by Hodder Press on 22 May, £22

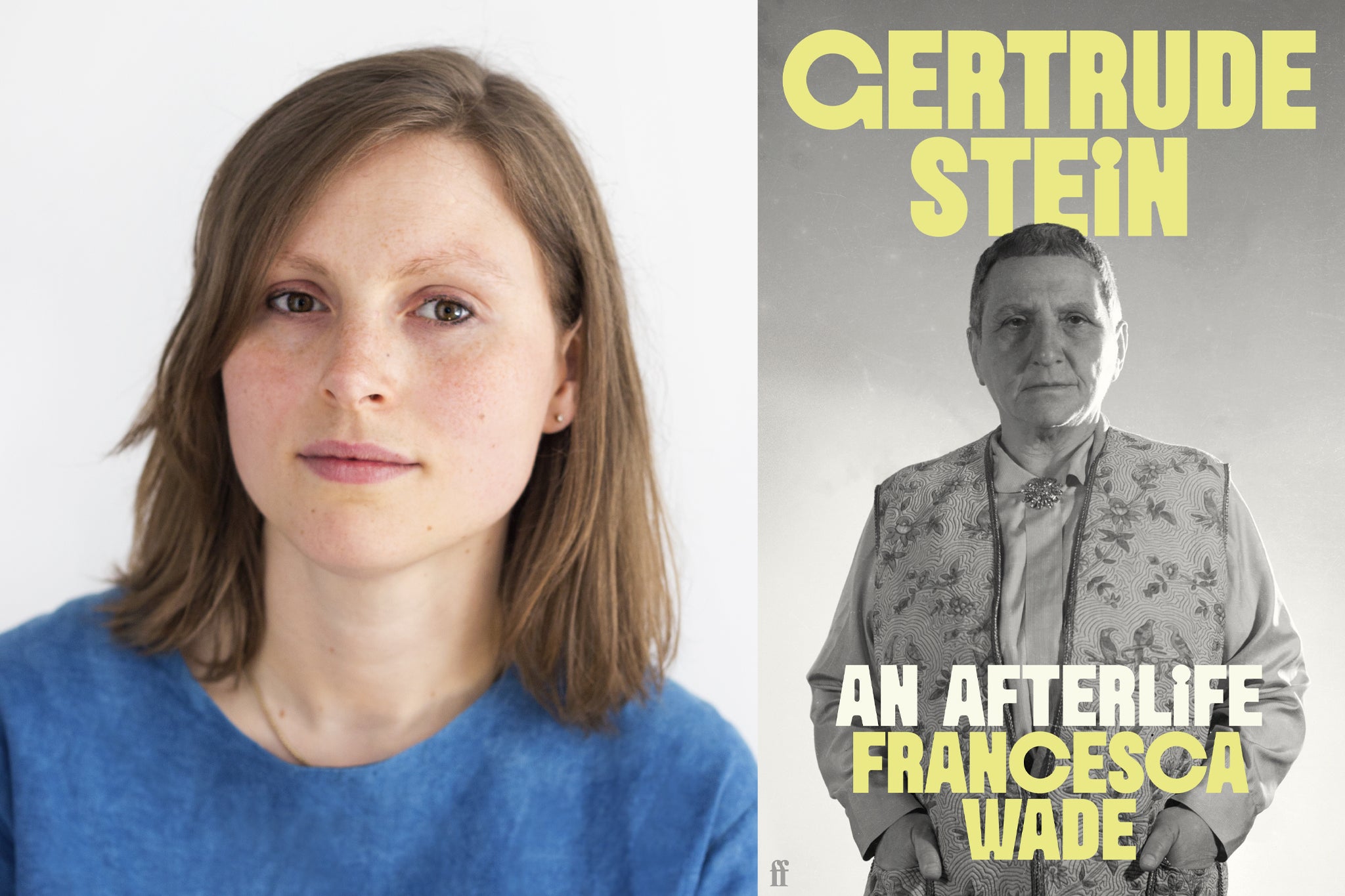

Biography of the month: Gertrude Stein: An Afterlife by Francesca Wade

★★★★☆

Gertrude Stein, hailed by fans as the godmother of literary modernism, was certainly a world-class braggart. Among the boasts collected in Francesca Wade’s Gertrude Stein: An Afterlife are “I have been the creative literary mind of the century”; that she believed she wrote “the only important literature that has come out of America since Henry James” and that “my books should be treated as classics”.

I should perhaps declare an acquaintance with Wade, a former newspaper colleague, although more relevant is my respect for her previous book Square Haunting, about the Bloomsbury set. Her Stein book has an adroit structure – the first part is more traditional biography, the second is about Stein’s posthumous legacy and cultural afterlife – and Wade benefits from being the first researcher to examine the rich archive of Stein material collected by Leon Katz.

Stein is a true curiosity. Some people rave about her work, others castigated her writing (“419 pages of drivel”; “gibberish” and “ghastly twaddle” are among the cutting descriptions) and she seemed to want abject adulation from everyone around (it was, oddly enough, provided by lots of obsequious young male fans). Although Wade dubs Stein a “megalomaniac”, the author offers a balanced account of her qualities, alongside the flaws.

The book is full of dynamic characters – including Stein’s friend Pablo Picasso – and much of the story focuses on Stein’s lover and longtime companion, Alice B Toklas. They called each other “Pussy” and “Lovey” and Toklas seemed to subsume her own life in service of Stein’s (“It was like she was “a passenger in her own life,” in Wade’s neat phrase). Even so, there was flint within Toklas, who was a grudge-bearer with influence. She detested Ernest Hemingway, for example, and boasted: “I made Gertrude get rid of him.” There seems to have been a lot of score-settling at the heart of Stein’s private circles, and Wade’s account of her wholly dysfunctional sibling relationships is revealing.

The biography did make me wonder how much Stein is even read nowadays (would many 21st-century readers have the appetite for her experimental prose and deliberate sabotage of syntax?), although Wade, better positioned than most, is convinced that “the humour of Stein’s writing shines through” some eight decades after her death in 1946, aged 72.

Wade provides lots of incidental details in this excellent, well-researched book, including that Stein’s “favourite sound” was that of a hooting owl. That detail alone made me warm to her, far more than her literary grandstanding.

‘Gertrude Stein: An Afterlife’ by Francesca Wade is published by Faber on 22 May, £20