Local elections historically have a pitiful turnout, and this year’s polls for councils, regional and mayoral seats in England – with an added parliamentary by-election in Runcorn – look set to be no exception.

But the lack of enthusiasm from voters to head to the ballot box does not prevent these from being the most significant non-parliamentary elections since 2008, when Boris Johnson deposed Labour’s Ken Livingstone to become London mayor.

Little did we know then, but that victory catapulted Mr Johnson into leading the successful Brexit campaign eight years later and then on to becoming prime minister in 2019.

The results, to be revealed on Friday 2 May, could equally be a herald of an oncoming earthquake about to shake up British politics.

We could be witnessing the slow death of the world’s oldest political party, the Tories, and the end of the two-party dominance that has gripped British democracy since Labour emerged in the 1920s.

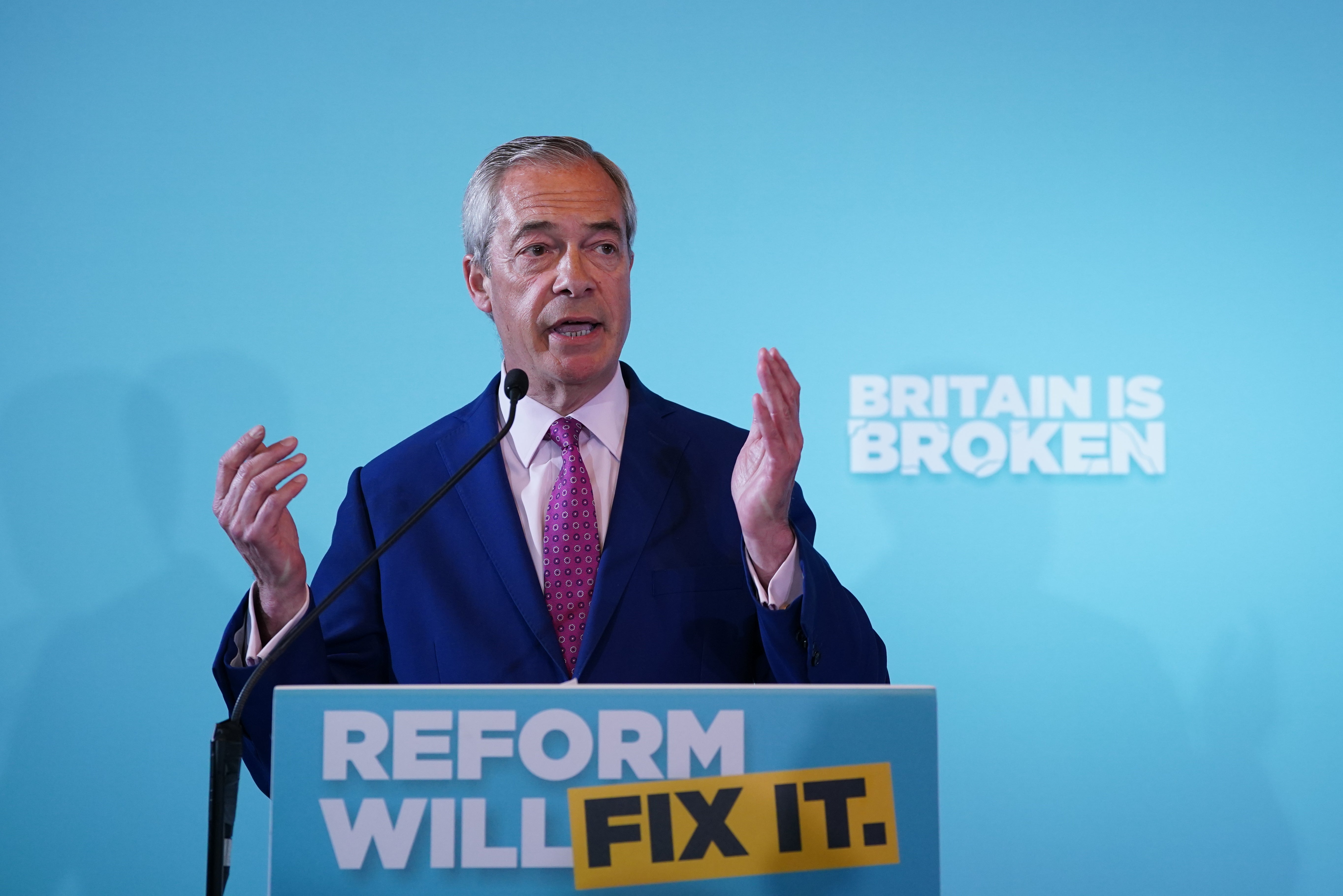

Most of all, these elections will provide a crucial test as to whether Nigel Farage and his Reform UK are just a by-product of opinion polls with no real substance, or a party to be taken seriously.

The battle for Middle England

In many ways, these elections are the battle for Middle England. The party which holds sway in many of these areas is the party whose leader ends up in Downing Street.

A total of 1,641 council seats are up for grabs, with the Tories defending 954 of them.

Of the 23 local authorities holding elections, 14 are county councils: Cambridgeshire, Derbyshire, Devon, Gloucestershire, Hertfordshire, Kent, Lancashire, Leicestershire, Lincolnshire, Nottinghamshire, Oxfordshire, Staffordshire, Warwickshire and Worcestershire.

Polls are also taking place in eight unitary authorities: Buckinghamshire, Cornwall, Durham, North Northamptonshire, Northumberland, Shropshire, West Northamptonshire and Wiltshire.

In addition, one metropolitan council, Doncaster, is holding an election.

Much to Mr Farage’s fury, further elections in Norfolk, Suffolk and Essex have been cancelled – all areas which Reform was set to grab. They will now take place next year with new mayoralties.

But a key test for them will be in the four combined-authority mayors being elected on 1 May, for Cambridgeshire and Peterborough, Greater Lincolnshire where former Tory MP Dame Andrea Jenkyns is standing, Hull and East Yorkshire and the West of England.

And maybe the biggest test of all will be the Runcorn and Helsby by-election, called because of the departure of disgraced former Labour MP Mike Amesbury after his conviction for assault. It’s a seat which the Tories have previously held and one Reform is favourite to win.

The future of Reform and Nigel Farage

Most of all, these elections are a test of whether Reform’s poll lead is reflected on the ground. During the general election last year the polls exaggerated Reform’s support by 5 per cent, which is one of the reasons they only ended up with five seats.

With a reduced turnout and a theoretically more motivated voter base, Reform should be making very significant gains.

But leading pollster, the Tory peer Lord Hayward, thinks Reform could win more than 400 council seats.

The party’s own private polling suggests they will win three mayoralties, in Lincolnshire, Hull and East Yorkshire, and Doncaster. They are within a shout of West of England with the self-styled “bad boy Brexiteer” Arron Banks.

Added to that they are the bookies’ favourite for the Runcorn by-election.

Failure to win those seats would be a setback for Reform.

However, victories could pose their own challenges as the party’s attempt to tightly control individuals which led to the forced departure of MP Rupert Lowe will become far more difficult.

A first test for Keir Starmer

It has not been an easy start in government for the prime minister and Labour, with riots following the killing of three young girls in Southport, Donald Trump, a flatlining economy, fury over winter fuel payments being scrapped, welfare for the disabled slashed, and a general dip in popularity.

Normally the first set of local elections a year into a new government represents a high point for a party, but nobody expects that for Sir Keir Starmer.

An example of this was when these same seats were contested in 2020, a year into Boris Johnson’s government, when the Tories surged to a by-election victory and won a record numbers of council seats.

Instead, Labour will be hoping that they can benefit for the continued split on the right between Reform and a near-collapsed Conservative Party.

If they go backwards from the pitiful 295 seats they are defending it will be very bad news for Labour indeed. But not terminal.

It could bring forward a cabinet reshuffle and names including chancellor Rachel Reeves could be in trouble.

A tough spot for Kemi Badenoch

If the local election omens look ill for Sir Keir and Labour, they look utterly dire for Kemi Badenoch and the Tories.

It appears that outside Lincolnshire they are no-hopers in the mayoral races and the Runcorn by-election.

Worse still, they stand little to no chance of holding on to more than half of the 954 council seats they are defending.

Even if the party recovered some support from last year’s general election, they will struggle to win council seats.

Much of this is expected in terms of Ms Badenoch’s leadership and if she somehow wins one of the mayoral races or above half the council seats it will be seen as a good night.

But less than half and a wipeout will only serve to fuel the whispering campaign against her short leadership since November. Already shadow justice secretary Robert Jenrick, the runner-up to Ms Badenoch in last year’s Tory leadership contest, is believed to be campaigning to replace her. Sir James Cleverly is another name being touted.

The main issue for the Tories next week will be whether Ms Badenoch can ensure they do less badly than feared and give herself breathing space to contest next year’s elections in Wales, Scotland and England.

Optimism for Sir Ed Davey and the Lib Dems

Sir Ed Davey makes more headlines for political stunts, such as falling into water, than he does for issues in parliament but he is set to be the other winner in the local elections – as Lib Dems often are.

There are rumours that the party could do well in some surprising areas as a possible replacement for Labour in a bid to block Reform, but, as ever, it is traditional Tory areas where they will most succeed.

The split centre-right vote between the Tories and Reform will see the Lib Dems come through the middle, especially in places such as Cambridgeshire, Devon, Gloucestershire and Hertfordshire.

With only 222 seats to defend it is highly likely that the Lib Dems will walk away with many more this time around.

But will it make them a party of government? The short answer is no, because local election surges have never done it for them before.