“Mama, you’re a bad bitch!” Beyoncé and Solange Knowles told their mum, Tina, after she finally divorced their father Mathew, in 2011. Aged 58, the mother of two global megastar daughters was quitting her “addiction” to an unfaithful and impulsive man she describes in her richly atmospheric memoir, Matriarch, as “a gifted salesman”, a “torturer” and a “master apologiser” who ultimately “came up empty” for her.

As the “Mama Bear” who instilled such fierce feminism and black pride in her daughters, it’s fascinating to read Knowles’ openhearted and insightful account of how she had unwittingly undervalued herself in a life spent building her own career then supporting the careers of both her gifted children. It will also make readers wonder how much of this parental modelling Beyoncé absorbed, as she has also stuck by Jay-Z (despite calling out his dalliances with “side chicks” including “Becky with the good hair” on her Lemonade album).

The 70-year-old mother knows better than to weigh in on any of that – heeding her daughter’s warning not to “spill too much tea [gossip]” in her book and briefly praising Jay-Z as a cherished son-in-law. Instead of an insider gawp at her celebrity family, the Texan former hairdresser has written a complex, thoughtful and deeply absorbing family history which tracks her matrilineal line from slavery to superstardom. As a seamstress who made all her daughters’ early stage costumes, Knowles has a keen eye for both the overall shape of a tale and the tiny sensory details that will connect readers to it.

Her own begins under the pecan tree that grew in her mother’s carefully tended back yard in Galveston, Texas. Beside the “scaly grey-brown trunk” of this tree – picking up nuts to be baked into pastries and pies – little Tina would listen to her own mother pass on the oral narrative that she writes down here. It dates back to 1800 when her great grandmother Rosalie – enslaved all her life in Louisiana – gave birth to Celestine (after whom she is named) who became pregnant in her teens by a man called Eloi Rene Broussard: the white grandson of the widow who owned them. When she died, Broussard bought his lover and both of their children for $1705, bringing them to live with him and his white wife (while Rosalie was sold to a relative and may never have seen her child and grandchildren again).

He would go on to have a total of ten children with Celestine, unusually acknowledging his paternity and leaving them a small plot of land at his death in 1904.

Knowles is crisp about the “fear and rage in my blood, the trauma passed down through my DNA” she feels on typing out that story. She’s also full of pride that Celestine “became free and got her kids free. They stayed together”. But although the family stayed together, their connection wasn’t always acknowledged by government paperwork. When Knowles’ mother, Agnes Buyince, gave birth to her children the hospital administrators refused to take her word on how to spell their surname. She was told there was a time that black people weren’t even given birth certificates and so she should be grateful for what she was given. So her kids ended up with different spellings: Beyince, Boyance and – for Tina – Beyonce.

You’re left boggling amid the chaos and poverty through which Agnes pulled her children from two marriages. She survived the bullying of her first husband and the weekend drinking sprees of her second (Tina’s handsome, illiterate father) – as well as briefly having to live with both men who became friends. Rebellious, distractible little Tina – who thinks she’d have been diagnosed with ADHD if she’d been born this century – grew up in awe of her mother’s hard slogging grit, but frustrated by the ways in which Agnes submitted to the unjust rules of racial segregation and the edicts of the Catholic church (never taking communion because she’d left her abusive first husband).

Because she had lighter skin and blonder hair than her siblings, Knowles recalls a painful incident in which a white woman on a bus assumed her darker-skinned older sister, Flo, must be her nanny. She shudders to recall the “twisted… snarl” of this woman’s face when she realised they were related.

Knowles writes that her elder brothers were repeatedly harassed by racist police. Family joker, Skip, was taken to a beach and beaten almost to death by officers who arrested him for falling asleep on a neighbour’s porch. “The cliché is that he was never the same, and it’s true. None of us were… I was afraid of how vulnerable I felt, and I wrapped that fear ion anger to protect it. I didn’t look for trouble, but I would be ready if it returned.” Inevitably, it did return. As a teenager, Knowles herself was subjected to a horrific strip search for a simple traffic violation.

But the family refused to be cowed. She’s proud to report that Flo took part in protests against segregated eating areas at Woolworths. It’s possible there’s a little myth making going on in the celebration of how the family appears to have stuck together, but as Knowles tells it they all supported her gay nephew Johnny (the child of her much older half-sister from Agnes’ first marriage) who made a name for himself styling local drag artists. He took her to a gay disco where she learned to embrace “black queer joy – claimed not for survival or resilience or even defiance, but for the fullness of joy.” It was also from Johnny that young Tina first learned hairdressing.

Knowles grew up to form a girl group, The Veltones, before starting her own hair salon for “professional women” in Houston. Charmed by Xerox salesman, Mathew Knowles (despite concerns about his impulsive overspending) she raised their daughters to challenge injustice. There are tender portraits of both the more self contained Beyoncé and storytelling Solange as young children. Beyoncé, we learn, did not sleep as an infant and could only be soothed by jazz albums, nodding off to the strains of Miles Davis’ trumpet and Gil Scott Heron’s socially conscious proto rap. She began adding harmonies to her mother’s nursery rhymes from early childhood but wasn’t always liked by other children in the playground – there’s a sad image of her at four pushing an empty swing – and as her performing talents grew there were more tuts about her pageant-winning attention seeking pizzazz.

You feel for Knowles as she struggles to support her starry-eyed kids (sewing their costumes and reading the small print on the contracts) while trying to keep them grounded. She becomes a mother hen to all the members of Destiny’s Child and pushes back hard on the rumour that Beyoncé was only using the other girls to launch a solo career. She calls out the industry’s racist assumption that the girls (with their “Motown” style) couldn’t aspire to the relatable style of white solo artists like Britney Spears. But instead of detailing their rapid ascent to celebrity, we’re drawn into the intimate world of a mother clambering on and off planes, altering hemlines with seconds to stage appearances and struggling to balance Solange’s need for homely structure with Beyoncé’s jet set existence.

A brutal critic of the tabloid culture which tears down megastars with “vicious lies”, Knowles is most ferocious when it comes to the rumours that Beyoncé faked her first full term pregnancy in 2012. Having witnessed her daughter’s heartbreak during multiple miscarriages, she’d used her skill with fabric to conceal the early stages of Blue Ivy’s gestation from the public. But she admits nothing had prepared her for the “helplessness” she felt in the face of the global gossip that denied her daughter’s hard-won motherhood. “Incensed,” she repeatedly begged Beyoncé to let her speak out but ultimately accepted that “anything I said would be plucked and chopped into endless articles until my name alone legitimised the discussion”.

Although her daughters’ creative reinventions have been the subject of global attention, this book makes it clear that both Beyoncé and Solange learned the art of self awareness and evolution from a woman who does not stop challenging herself and moving with the times. She’s very direct about the many times she left Mathew Knowles (the flights to new homes with her distressed daughters) and the romance of their repeated reconciliations before she was finally able to leave him.

She divorced her second husband, Richard Lawson, at 68 and has survived breast cancer to enjoy life as a grandmother still open to fresh ideas on the horizon. After her childhood struggles with Catholicism, and Beyoncé’s Lemonade critique of the way the church has shamed female sexuality, it is interesting that Knowles still appears to have so much faith in a Christian God and the bible. But this also fits into her need to honour tradition while seeking new interpretations of life’s infinite possibilities.

As a mother, I closed this book in awe of Knowles’ hard grafting, hard loving, open minded and humbly accountable parenting ethos. No wonder her girls grew up to feel they could run the world.

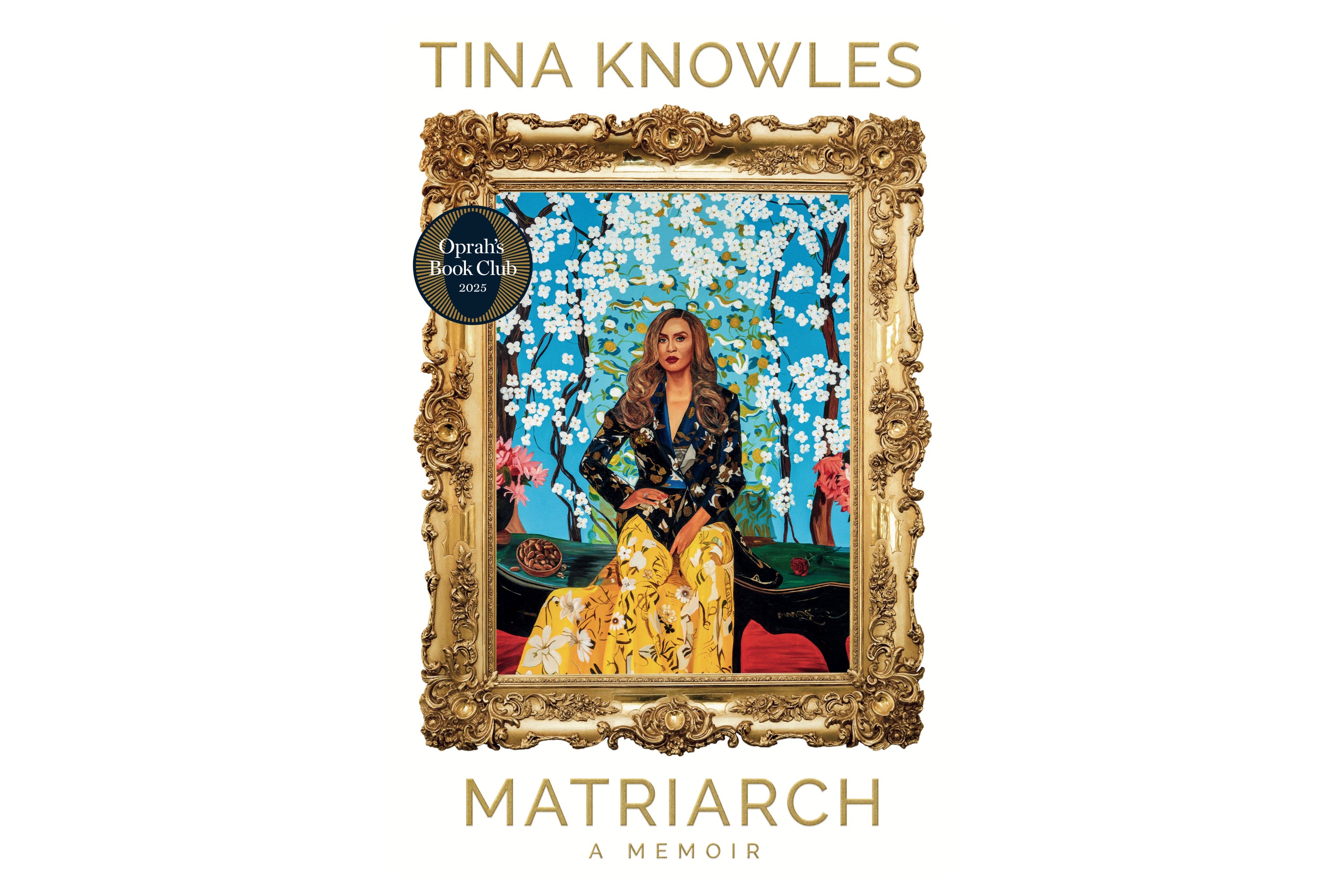

‘Matriarch’ by Tina Knowles is out now