250 years ago this month the American War of Independence broke out amidst the sleepy farmlands of eastern Massachusetts, which had followed the resistance to the infamous Tea Act of May 1773, and the imposition of the coercive ‘Intolerable Acts’ less than two years previously.

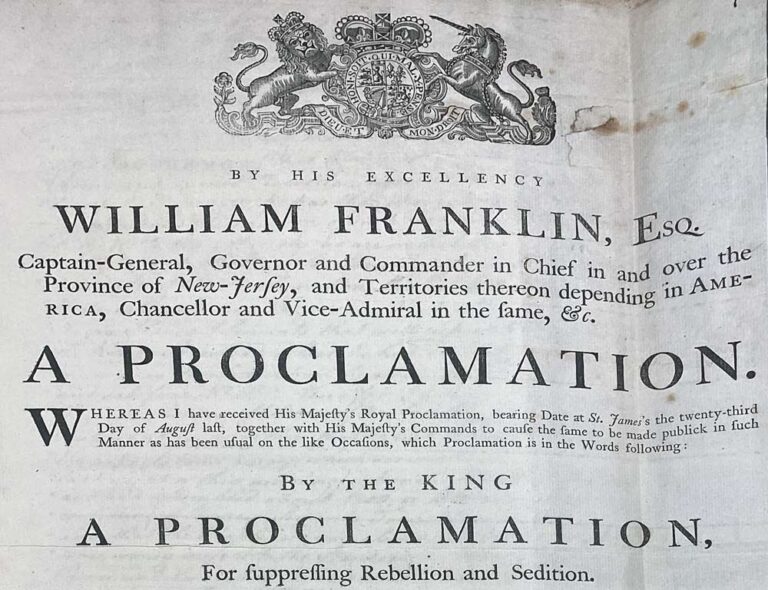

The Massachusetts Colonial Congress formed a patriot provisional government late in 1774. By February 1775, the British authorities declared Massachusetts to be in a state of rebellion and resolved to punish the colony, and Boston in particular for its continuing opposition to the Crown.

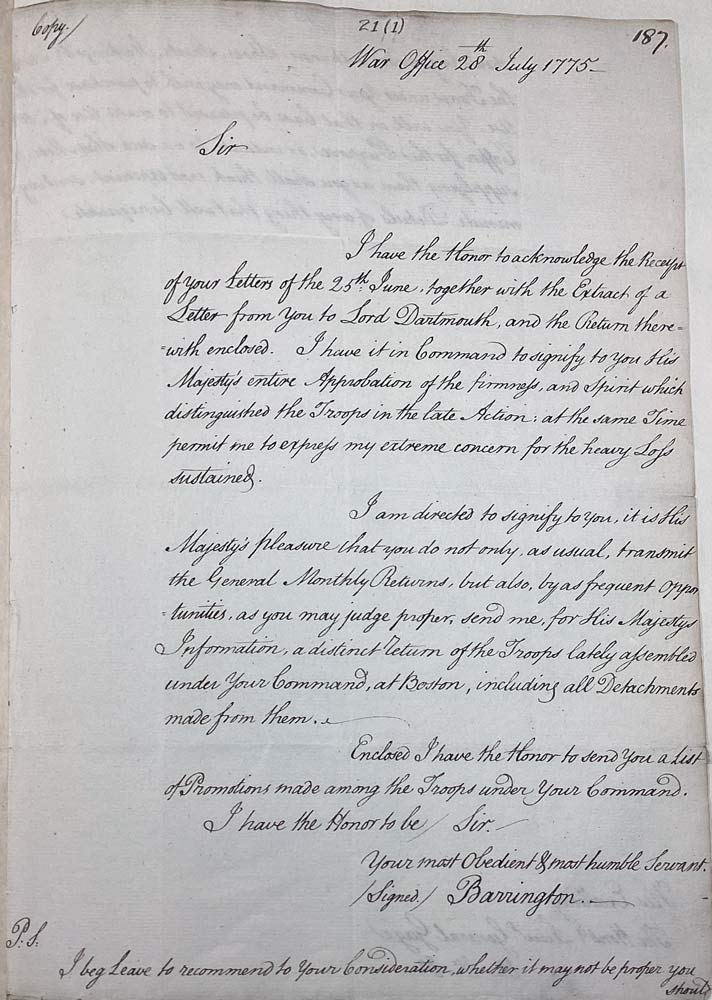

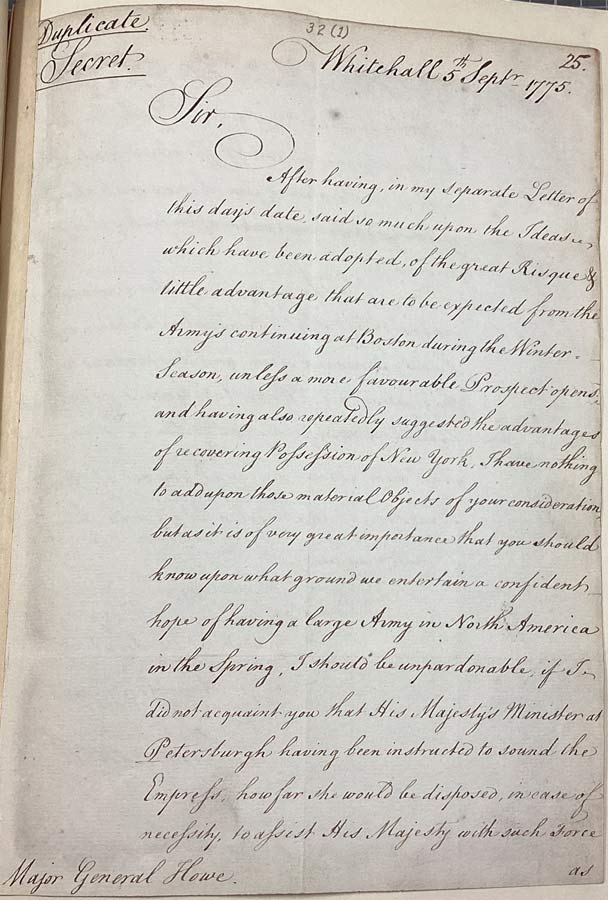

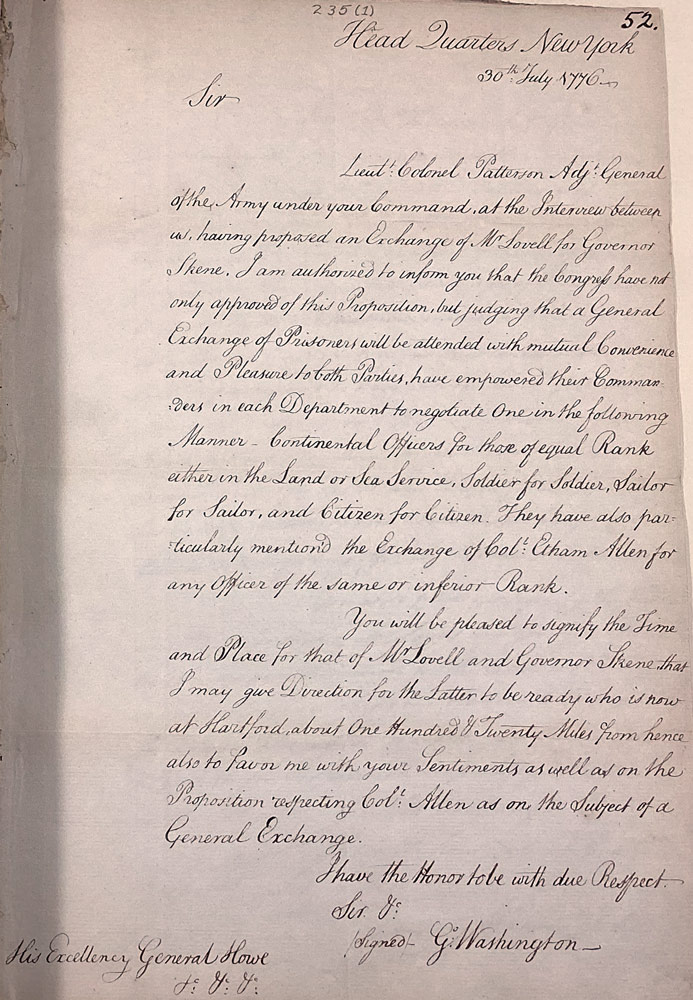

Our records, of orders from King George III, military despatches, and newspaper reports, give a unique perspective into this opening phase of the revolutionary war.

Starting with defence

While it took eight long years to end the conflict, British colonial objectives were initially defensive and limited in scope. Patriot Americans fought to protect their liberty and to preserve their autonomy. For 18 months they struggled to contain British Crown forces while debating what their ultimate goal should be.

During the summer of 1776, they defined their objective as total separation and declared independence. Yet declaring independence was very different to actually achieving it. King George III’s government, under Prime Minister Frederick, Lord North regarded their actions as no more than insurrection and remained determined to crush them.

Lexington and Concord

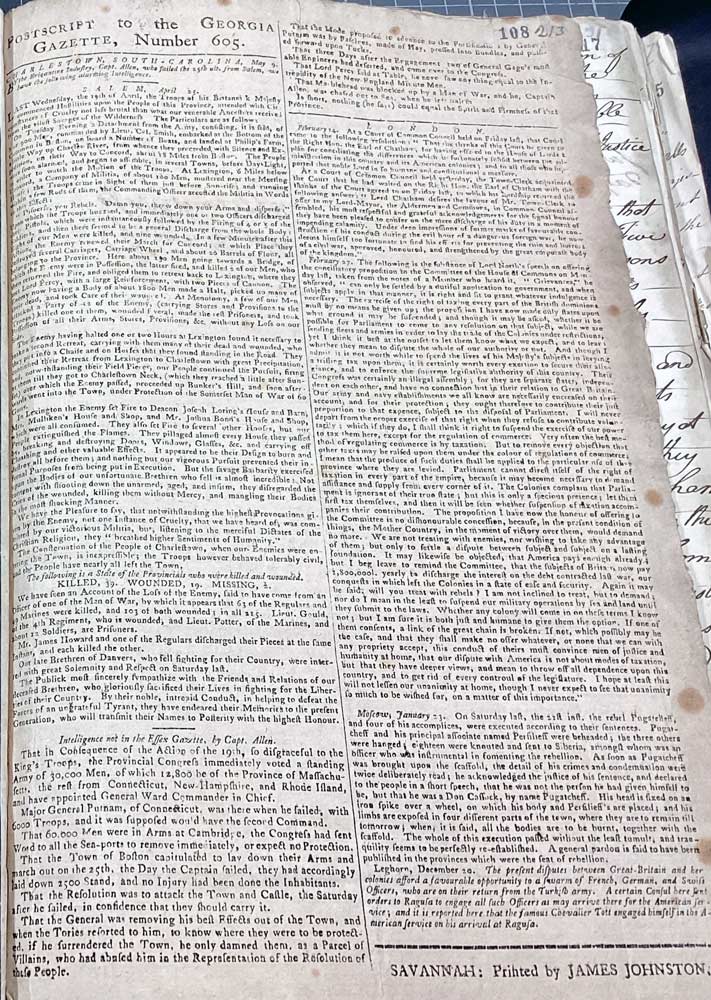

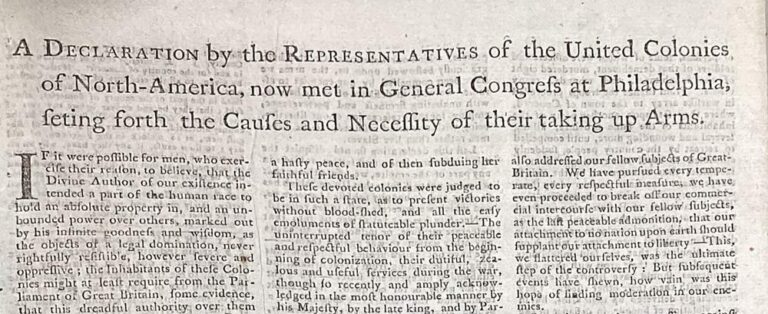

The first phase of the war was relatively short. News of the opening actions at Lexington and Concord (both fought on 19 April 1775) spread so rapidly that the middle Atlantic colonies had heard news of it within a week, the Carolinas and Georgia were printing accounts of it by the end of May.

For the time being conduct of operations remained in New England hands. Within a short time, the Massachusetts Bay Colony, Connecticut, Rhode Island, and New Hampshire had sent almost 26,000 men to participate in besieging General Thomas Gage in Boston, but there was no united command structure.

Other colonies (such as Virginia, and Maryland) began organising for war, but the majority were too occupied with their own problems to send assistance northwards.

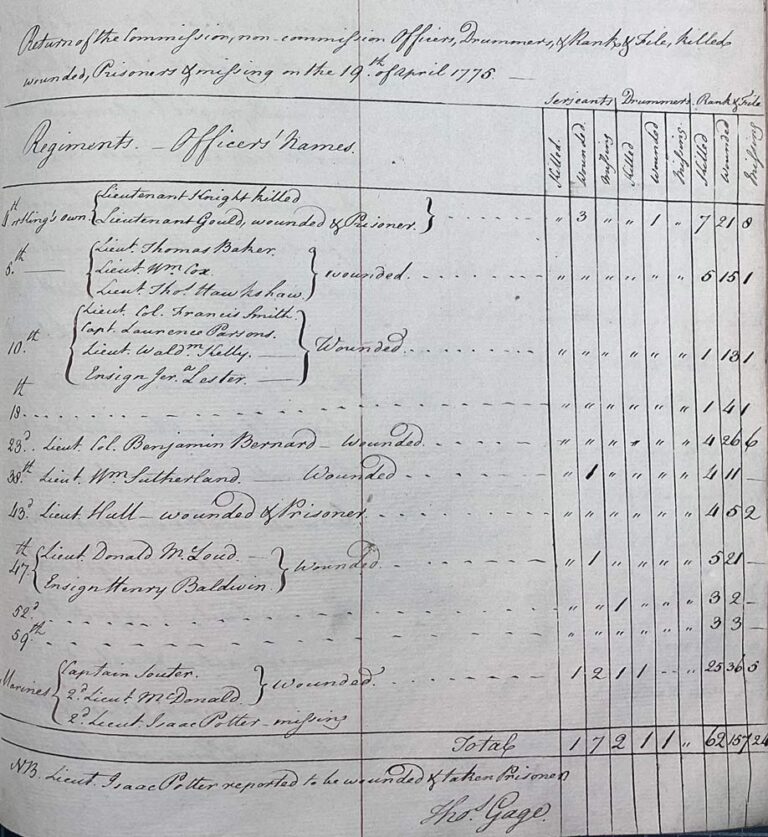

The British under Lieutenant Colonel Francis Smith having marched into the rural towns of Lexington and Concord intended to supress the possibility of rebellion by seizing weapons from the colonists. Instead, their actions sparked the first engagements of the war. The New Englanders having raised the alarm summoned the highly trained minutemen and local militia companies which enabled them to successfully counter the British threat.

Compromise or conflict?

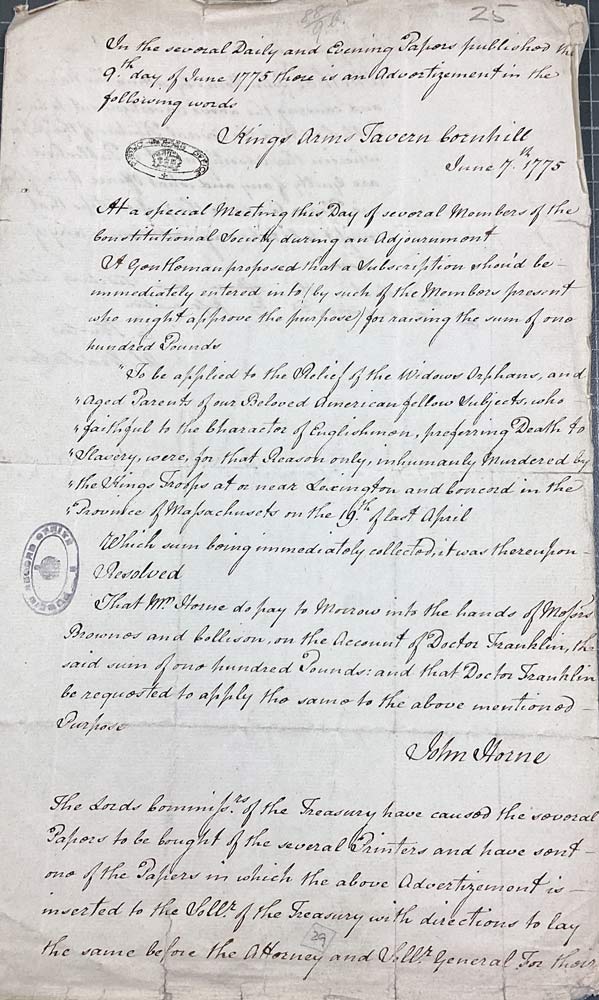

Although only a relatively small number of colonists wished for independence at the outbreak of the fighting, the strength of separatist feeling within this minority meant that compromise on terms acceptable to the British government appeared increasingly unlikely. Anything else was outwardly unacceptable to the British political nation, however, there was a significant lobby of support for conciliation, together with growing entrepreneurial sympathy for the colonial cause itself.

For George III it was a conflict not only about the authority of a sovereign parliament, but also against the moral challenges of disorder. Prior to 1775 the Americans had tended to focus hostility on ministers (like Lord Dartmouth, Secretary of State for the Colonies) and Westminster alike, believing them to be responsible for unwelcome legislation, there was a major shift as many colonists now considered the king himself to be the cause of their grievances.

The second year of fighting

Britain’s military leaders were to find that 1775 was to be a disastrous year. They did not appreciate the scale and logistical difficulties of the task facing them in colonial America until too late, and they initially allowed the bulk of their forces to become bogged down in an exposed base. While the British position collapsed throughout much of North America, by the end of the year Lord North’s Tory administration faced the prospect that it might lose Canada as well as the 13 Colonies, after the launch of a Patriot-led expedition against Quebec.

For the American side the year was marked by the successful encirclement of Boston, a committed stand at nearby Bunker Hill, the creation of a national army, the Continental Army under the Virginian George Washington, and the invasion of Canada.

While the Patriot militia were easily scattered at Lexington, Concord was not such a straightforward fight. British forces were not able to occupy the undefended town but then withdrew in the face of pressure from the militiamen. On their route back to Lexington they suffered heavily from sniping, their flanking manoeuvres being insufficient to prevent ambushes and renewed attacks on their way back to Boston.

The larger Battle of Bunker Hill, which was fought on 17 June during the Siege of Boston, though a tactical victory for the British, proved to be a costly encounter, for they suffered more than twice the number of casualties as the Americans, including many officers.

A force to be reckoned with

The engagement fully demonstrated the possibility that inexperienced militia could stand up to regular troops in battle. Subsequently, the action discouraged the British from further frontal attacks against well defended positions. Bunker (or more specifically Breed’s) Hill led General William Howe, who would replace Gage as commander-in-chief, to adopt a more cautious approach to future planning, which was demonstrated in the following New York, and New Jersey campaigns.

The costly encounter also convinced the British Crown of the need to hire substantial numbers of Hessian and other German auxiliaries to bolster their strength in the face of the new and formidable Continental Army, while plans to contract Russian troops from Catherine the Great were far less successful.

Taking New York

In this first stage of the war, the British Army became trapped in the peninsula city of Boston, which they were forced to abandon on 17 March 1776, sailing to Halifax, Nova Scotia to await reinforcements.

Washington relocating his army to defend the port city of New York, located at the southern end of Manhattan Island, established defences there and awaited the British attack. Landing unopposed on the sparsely settled Staten Island, General Howe was reinforced by a Royal Navy fleet under his elder brother, the peace commissioner Admiral Richard Howe in Lower New York Bay, bringing up his total strength to 32,000 men.

On 21 August, Crown troops attacked the American redoubts on Long Island. Unknown to the Continental forces, Howe had brought his main army around their rear and attacked their flank soon after. The Americans panicked, resulting in a high rate of casualties and captures. The remainder of their army retreated to the main defences on Brooklyn Heights, where the British dug in for a siege. However, Washington evacuated his entire army on the night of 21–22 August. Being driven out of Manhattan entirely after several more defeats, he was forced to retreat through New Jersey and crossed the Delaware River into Pennsylvania.

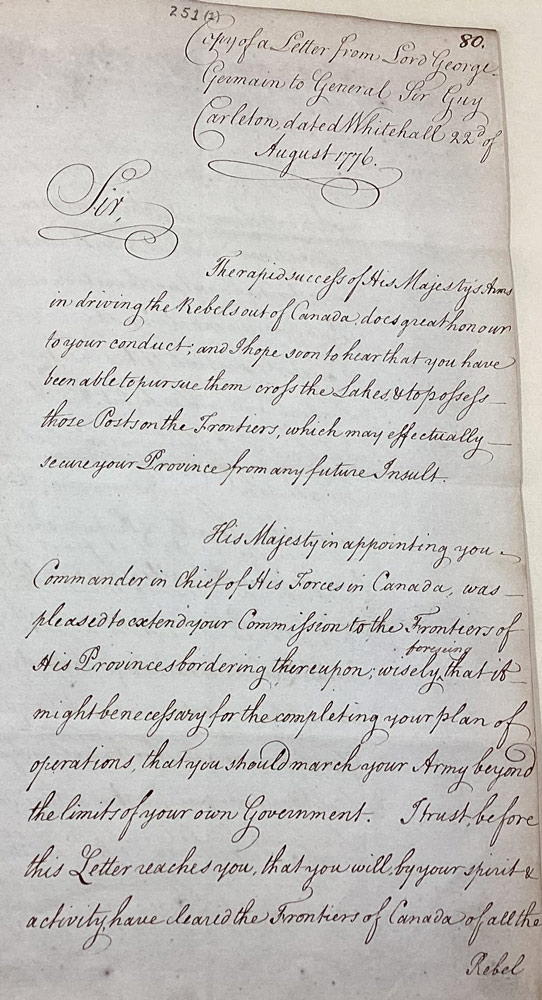

The Battle of Long Island was the first major engagement to take place after the ‘United States’ Continental Congress had declared its independence at Philadelphia on 4 July. The British capture of strategically important New York, which along with much of its neighbouring territory (i.e. Long Island and an enclave in northern New Jersey) they held for the remainder of the war, and was not finally evacuated until as late as September 1783 under its last military governor, the resourceful Sir Guy Carleton.

Digging in

Long Island would prove to be the largest encounter of the Revolutionary War in terms of troop deployment and combat. Its most important legacy showed that there would be no easy victory, and that the struggle would be long and bloody.

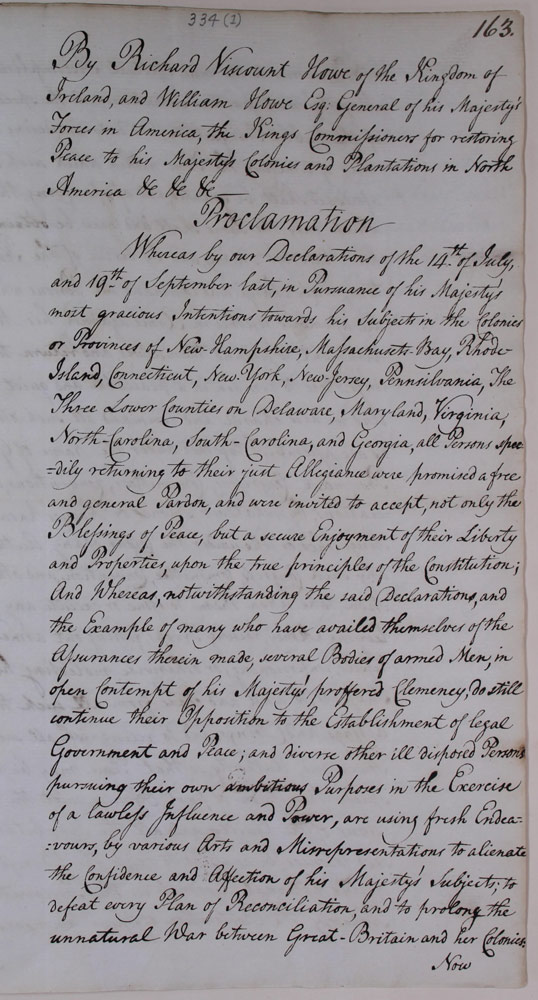

With British military command firmly established in New York, the city became a place of refuge for loyalists from all over the colonies, and a focal point for espionage and intelligence gathering. Moreover, following the November reissuing of the Howe’s offer of amnesty to anyone who had taken up arms against the Crown, New Jersey itself became a civil battlefield with mounting loyalist militia activity, as well as being a hotbed for spying and counter-spying.

Reports of the amnesty decree were met with some surprise, as its terms were more lenient than the hard-liners in North’s administration expected. Whereas politicians who would oppose the war (like the Whigs Charles James Fox, the Marquis of Rockingham, and the radical MP for Middlesex John Wilkes in particular), pointed out that the November proclamation had ultimately failed to mention the primacy of parliament itself.

While news of the capture of New York was favourably received in London, and General Howe was awarded the Order of the Bath for his services, combined with the recovery of Quebec and Montreal, circumstances suggested to the British high command that the war could be ended with a final year’s campaigning. Indeed, only time would tell.

Bibliography

- Black Jeremy , War for America , The Fight for Independence (1991).

- Black Jeremy , George III, America’s Last King (2006).

- Bonwick, Colin, The American Revolution (1991).

- Morrisey, Brendan, Boston 1775 (1993).

- Schecter, Barnet, The Battle for New York, A City at the Heart of the American Revolution (2003).