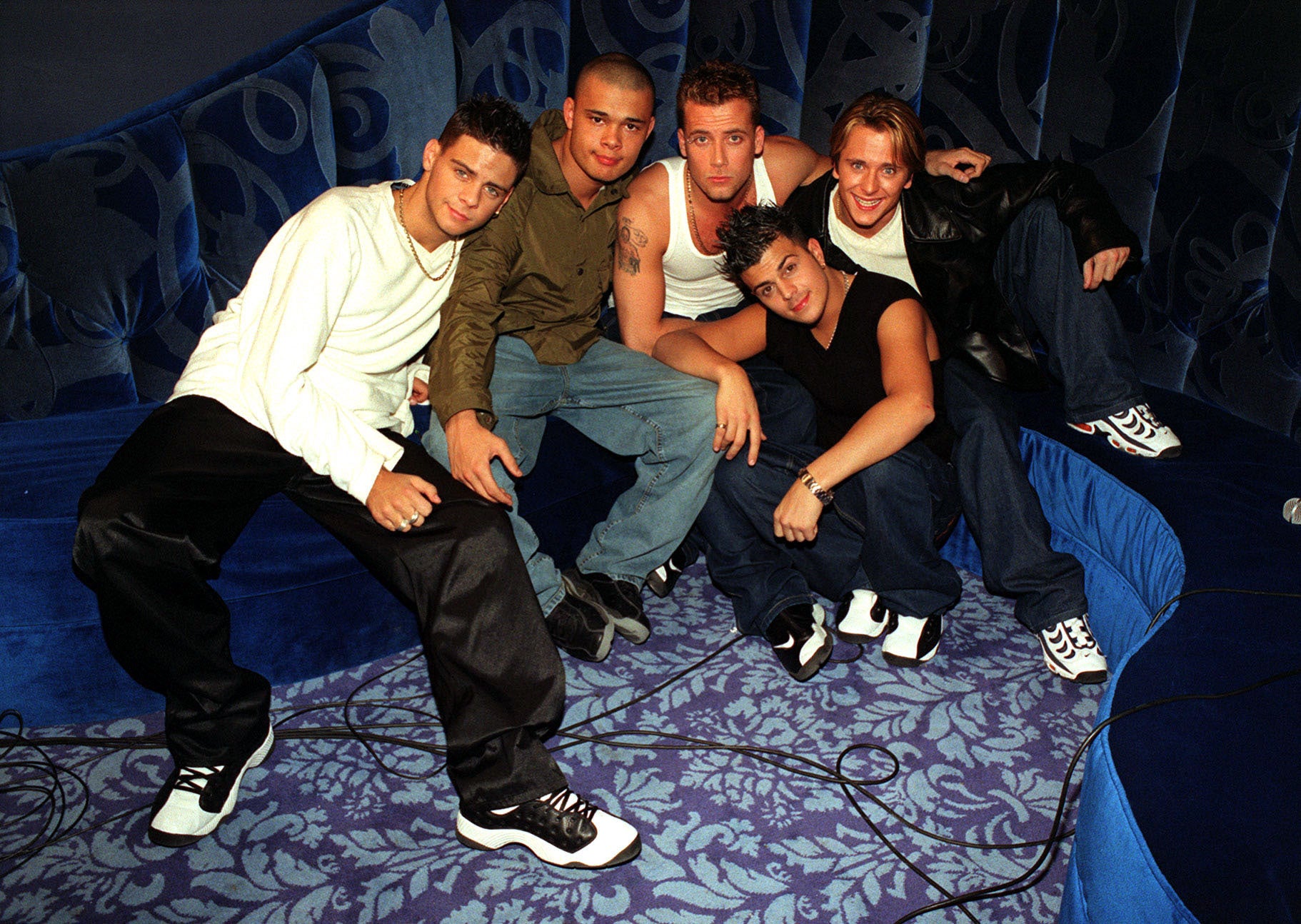

Summer 1998: Five are top of the album charts and have just released the video for their new single “Everybody Get Up”. In it, pupils rebel against a boring exam; they whack their rulers in unison against desks to summon the five bad boys every teacher and mother of girls should be terrified of. “Ha ha!” Jason “J” Brown laughs as he leads the boys in, wearing a hat to show he’s the eldest. Spiky-haired, chain-wearing Abz Love, the naughtiest one, turns off the power to the room. Then in comes the blond one, Ritchie Neville, along with gobby Scott Robinson (who throws an evil little grin to the other lads) and baby-faced Sean Conlon (obviously the sensitive one). Each has a different role within Britain’s biggest new boyband, but their joint identity has been crafted to appeal to teen girls for whom the other boybands seem too wet, too girly. Three years and 11 Top 10 singles later, it will all be over.

Today, the grown adult members of boyband Five are running an impromptu massage parlour. Scott stands over a seated and blissed-out Ritchie, giving his shoulders a kneading. This has piqued the interest of Abz, who wants in on the action; Scott dutifully obliges. J and Sean watch on amused. “We don’t need more stress,” Scott will say, almost sternly, in his gruff Essex accent in a few minutes’ time. Despite their mischievous image, this was a very stressed-out boyband – ill, in fact, from the 24/7 pressurised schedule of travelling the world promoting hits like the optimistic jam “Keep on Movin’” and rap-rock Queen collaboration cover “We Will Rock You” to insatiable fans. If they’re doing this again as a manband, it has to be different.

They’re no longer in their teens, but their forties – now in age-appropriate smart-casual black outfits (plus what feels like emotional armour in the form of immovable dark sunglasses for Abz). As Sean puts it, “We’ve got communication now; before it was all lad banter.” Just a few months ago, I watched Five members in the recent BBC docu-series Boybands Forever, which chronicled the dark side of being in a 1990s British boyband. It’s odd, given Scott’s tears on the show over his appalling experience of fame, to have them here sitting around a boardroom table in an office just off Oxford Street, grinning and cracking jokes. There’s a boyish hyperactivity in the air, a distinct disbelief that all five of them are in the same room again to promote their band’s reunion tour.

Before I can ask my first proper question, conversation descends into comparing notes on whose fault it was that they broke up in 2001. A neutral statement at the time gently said the band could “no longer do justice” to their fans or each other. In reality, they were all having a mental health crisis on some level or another. In Boybands Forever, the cause of the split is wrongly framed as being a result of Scott’s breakdown, though Scott says he is unbothered by the edit because he’s always felt deeply responsible for the breakup. Sean leans over the table to more clearly face Scott, who is sitting next to him, and tells him that that’s crazy, because he has always carried the blame on his shoulders. “I was the first one to fall,” Sean insists. “When we did [chart-topping 2001 single] ‘Let’s Dance’, we were at the beginning of the promotion of the album [Kingsize] and it’s not an ideal time to have a breakdown from the record company’s point of view at all.” They all laugh grimly.

Sean remembers it quite vividly. “J came up to me and he said, ‘You’re not right mate. I really think you need to get some help.’ I don’t want to get emotional…” his eyes start to water during this retelling, and Scott gives him a thumping pat on the back. After that intervention, Sean had a brief break from the band to get counselling and their team told the world that he was resting up from glandular fever. The band had to film the “Let’s Dance” video without him; a cardboard cut-out of Sean bobs up and down in the background.

Shortly after this, while Sean was absent, Scott marched into the record label’s office and got into an escalating physical fight with one of their team who refused to let him quit the band, pinning him against a desk. Simon Cowell had to intervene, nearly punching Scott. Following that was a meeting between Scott and the band while they were getting ready for a Top of the Pops performance; Scott had planned to tell his friends and bandmates he was going to leave. “You came in and lost the plot, crying your eyes out – I mean that weeping where someone can’t actually speak,” Ritchie says to Scott, performing the heaviness of those sobs. “Me and J went out in the corridor and I said, ‘It’s done, ain’t it?’ Because nothing is worth that, it doesn’t matter how many No 1s you get, it ain’t worth that.”

But all five of them were emotionally and mentally suffering. “We should have had six months off,” says Ritchie. It’s a shame, J adds, that the industry didn’t recognise they were struggling and support a hiatus; if they had, they might have been able to have a much longer career. “It’s taken us 25 years – I’m not even joking – literally 25 years to be able to even get my head around it,” adds Ritchie.

“It’s almost like we’ve been traumatised,” says Sean, as if coming out of a daze.

“No, we are traumatised,” says Ritchie, with a look directly at me.

What they’re traumatised from is worth examining. Their young lives changed overnight in 1997 after they successfully auditioned in an open-casting call for a boyband with “attitude and edge”. They were signed by Simon Cowell and RCA there and then. Their eclectic pop sound was a new blend of US hip hop, provided by rappers J and Abz, and spikier boyband pop, crooned and sung by the other three. They were thrown together to live in the same house by their management, but their ages meant that Sean, the youngest at just 15, was cohabiting with J, who was about to turn 21. (“So that gives you a gauge of the age [we were] and what was going on in the house – and we kind of ran riot…” J says ominously, which I assume means casual sex and partying.)

Five were instantly famous, their debut album not just No 1 in the UK but seriously successful on a global scale. Fans camped out all around the madhouse, so the band felt constantly observed; they’d often do an “SAS job” and pretend to be out, just creeping around in the dark to get some “mental headspace”, says Richie.

Enjoy unlimited access to 100 million ad-free songs and podcasts with Amazon Music

Sign up now for a 30-day free trial

Sign up

Enjoy unlimited access to 100 million ad-free songs and podcasts with Amazon Music

Sign up now for a 30-day free trial

Sign up

It sounds like the female attention warped their young minds with paranoia (bar Abz, who grins like a sated cat about the never-ending line of girls: “It was good to me, and I enjoyed the process”). At the very start, the rest of them loved it, too. But it quickly became tiresome when they craved normal life, without being mobbed by fans; in a pre-internet era, they couldn’t even buy their family gifts for Christmas. “It made me feel really weird because I’d think all the other people in the street were thinking, ‘Look at this idiot, who does he think he is?’” J says. Sean agrees, “You got scared that people thought you were arrogant.” Then Ritchie adds about the touching and grabbing: “I didn’t know if somebody was overstepping – obviously certain boundaries, I did – but if somebody’s taking the p***, I didn’t have a good gauge of what that was.”

I see how Scott became the “main one” in Five’s episode of the BBC series. He’s clearly the storyteller of the group, and goes into great detail recalling those incidents that forever altered his psyche. There was the occasion Five were in a Tokyo hotel after mini-disc players had just gone on the market. Scott desperately wanted one, as well as the experience of going into a shop with his own money and choosing it. He told the two security guards outside his hotel door that he was popping out to buy one but they said he had to be accompanied by five bodyguards. Fans mobbed him and the bodyguards almost immediately, ripping at their clothes. “I go into the shop and I’m looking for about a minute and then the fans, they’re not trying to be rude, they’re not trying to break things, but they’re so excited that they broke the shop windows to get to me. And the shopkeeper went, ‘Just take it, just take it!’ So I didn’t pay for it, and then I cried in my room because I had stolen this thing. But I had been told to steal it. And I just sat there and I cried. And I went, ‘It’s not the one I wanted.’ I cried myself to sleep.”

They’d constantly wake up and not know which continent they were on, having to look out the hotel or car window for clues. J in particular suffered with this. “I went through the whole [experience] with chronic insomnia, from about three months after it all kicked off,” he remembers. “Most nights I was getting maximum three-and-a-half-hours’ sleep. Sometimes I’d go four or five days on an hour and a half, and then have to get up at five in the morning and film a new video.” It had a diabolical compounding impact on his mental, emotional and physical health.

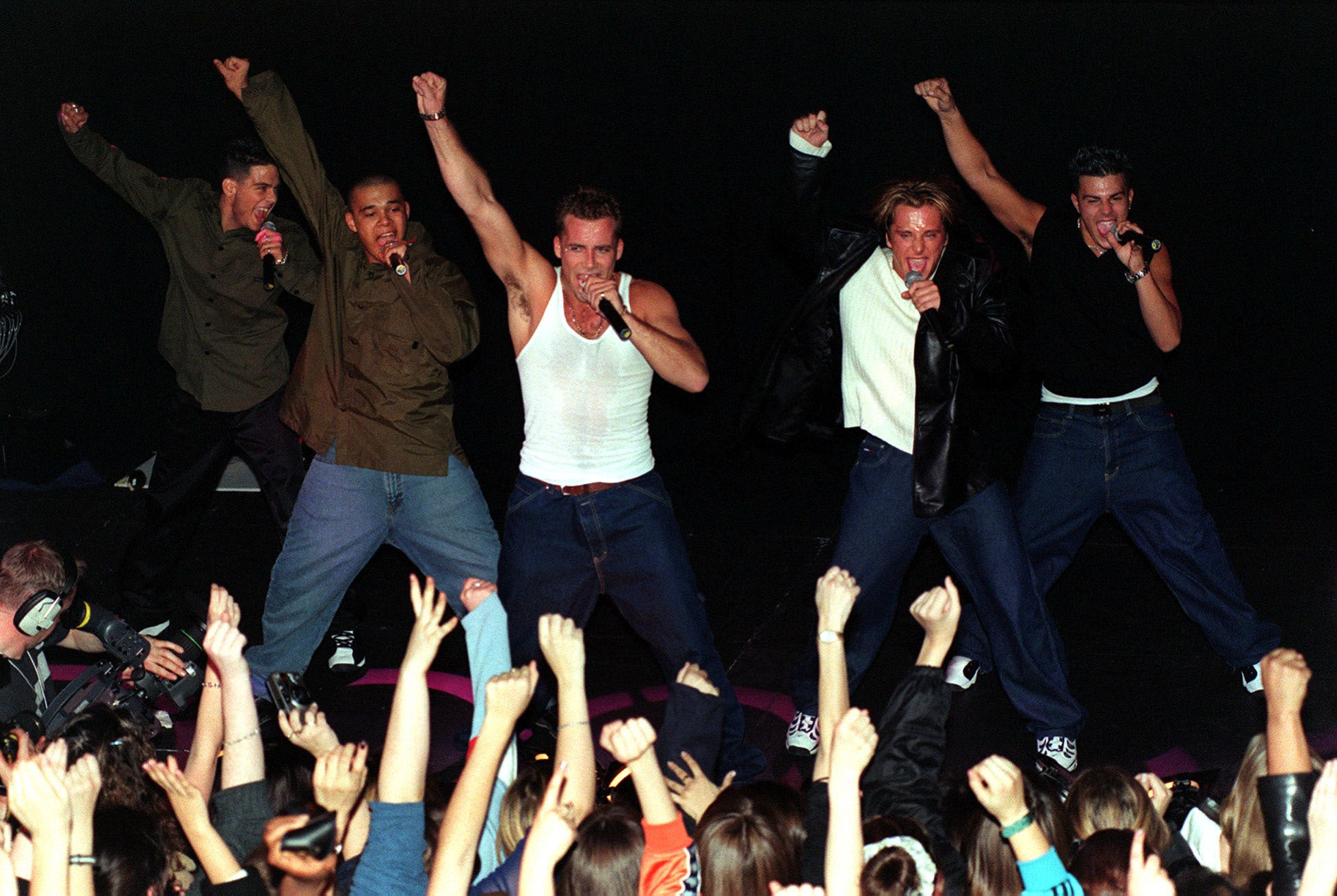

The band is keen to impress on me that it wasn’t all doom and gloom; there were moments in this slog that shone through, including No 1 singles and playing Rock in Rio to an audience of half a million people. The subtext seems to be that the joy came from the band’s togetherness, away from the individual members feeling alone in the madness.

After the band broke up, Scott got married to his partner the very next day, a straight life swap for stability with his wife and future family. The others fell apart without that structure. “Jesus, straight after the band, for three years I was sat in a living room, frozen, drinking too much, completely lost,” says Ritchie. “I used to say, ‘I feel like I’m a rowing boat in the sea with no oars or sail.’” Sean compares their situation to being in early retirement. “I had that at 20 years of age: I had some money in the bank and enough not to work,” he says. “In your mind there was no Everest, because whatever I do it’s not going to be bigger or better than Five. And you’ve still got an ego and want success at that age, so it’s a really troubling, conflicted time.”

What was unique about Abz’s situation is that he was the only one who didn’t want the band to end. His turbulent life after the split is well documented in the media: drug addiction, isolation and paying for friends; bankruptcy; suicidal ideation; going cold turkey. “I thought we went hard in the band – I went rock and roller after the band… that life just pulled me in,” he says.

Five tried to reunite a few times to varying degrees of success. In 2020, when Scott, Ritchie and Sean got back together and went on This Morning, viewers made predictable jokes like, “They should change their name to Three.” Clearly, it needed to be a cultural moment like this, in which, they collectively insist, no one is being dragged along, more reluctant than the others; they’re all hungry for a proper second chance.

It wasn’t until they were approached by Louis Theroux’s production company to make Boybands Forever that they all started to consider what a reunion could look like. Scott booked an Airbnb and the members met, hung out, shared some drinks and laughs, and decided the time was right. Scott reached out to Simon Cowell about the physical scuffle (no hard feelings there, he insists) and much to their amusement, the guy at the label that Scott fought with, Rob Wicks, is now their new manager.

Abz has been more reserved for most of our interview, content to let the others speak, but when he is finally nudged into talking he focuses on the positive, the present. “What I feel like I want to say is how proud I am of these guys and how brave they are to put themselves into this environment again,” he says in his strong London accent.

They’ve reassessed their music – the same music they used to apologise for in the pub when men approached them to ask, “Aren’t you those guys from that boyband?” or began singing “Keep on Movin’” to them. “The industry’s attitude towards this 90s era of pop was, ‘It’s bubblegum pop, it’s not going to last, it’s superficial,’ especially after the wave of indie bands before that,” explains Sean. “We internalised that attitude, too, thinking, ‘Oh, we’re not really doing anything meaningful, it’s not impacting anyone’s life, it doesn’t really mean anything, it’s not real music.’ It also ties back to why we were so overworked and stressed – because of that mindset. The focus was on making as much money as possible and moving as quickly as we could. At the time, no one would have expected that, 25 years later, there would still be interest in the band and our music.”

Now any personal embarrassment over their music has gone; all say they love it and find it joyful and unique. It’s made them view their fans in a completely different way as well. “I can see that the fans are really genuine, it did touch them,” Sean adds. “Because I used to be like, ‘Why are they going mad about that song when it’s not that great?’”

Unless Calvin Harris calls them up and asks if they want to make a “summer banger”, they’re probably not going to make new music. “A lot of times, people don’t want that, do they?” says J, pragmatically. “They want to hear all the bangers they remember.”

The focus is entirely on having the most fun as possible at reunion shows they promise will be like a giant school disco. “It’s about the hits, the tour, reconnecting,” lists Sean. Then Scott says, unironically, “Keep on Movin’.” One of them adds, “Tickets out now.” It’s been nearly a quarter of a century but they still remember the game that the pop machine requires – this time they’re prepared to play it.

Tickets are available now for Five’s ‘Keep on Movin’ 2025 Tour’ which starts this autumn