Japan is running out of workers. With an unemployment rate of just 2.5 per cent, a rapidly ageing population and declining birth rate, finding enough people to fill roles as taxi drivers, baristas and waiters is proving a major challenge to the country’s economy.

One inventor has created a solution that not only allows disabled people greater access to the workplace, potentially tapping into a hugely underutilised section of the population but could one day let older people keep active even as their bodies age – and stave off loneliness in the process.

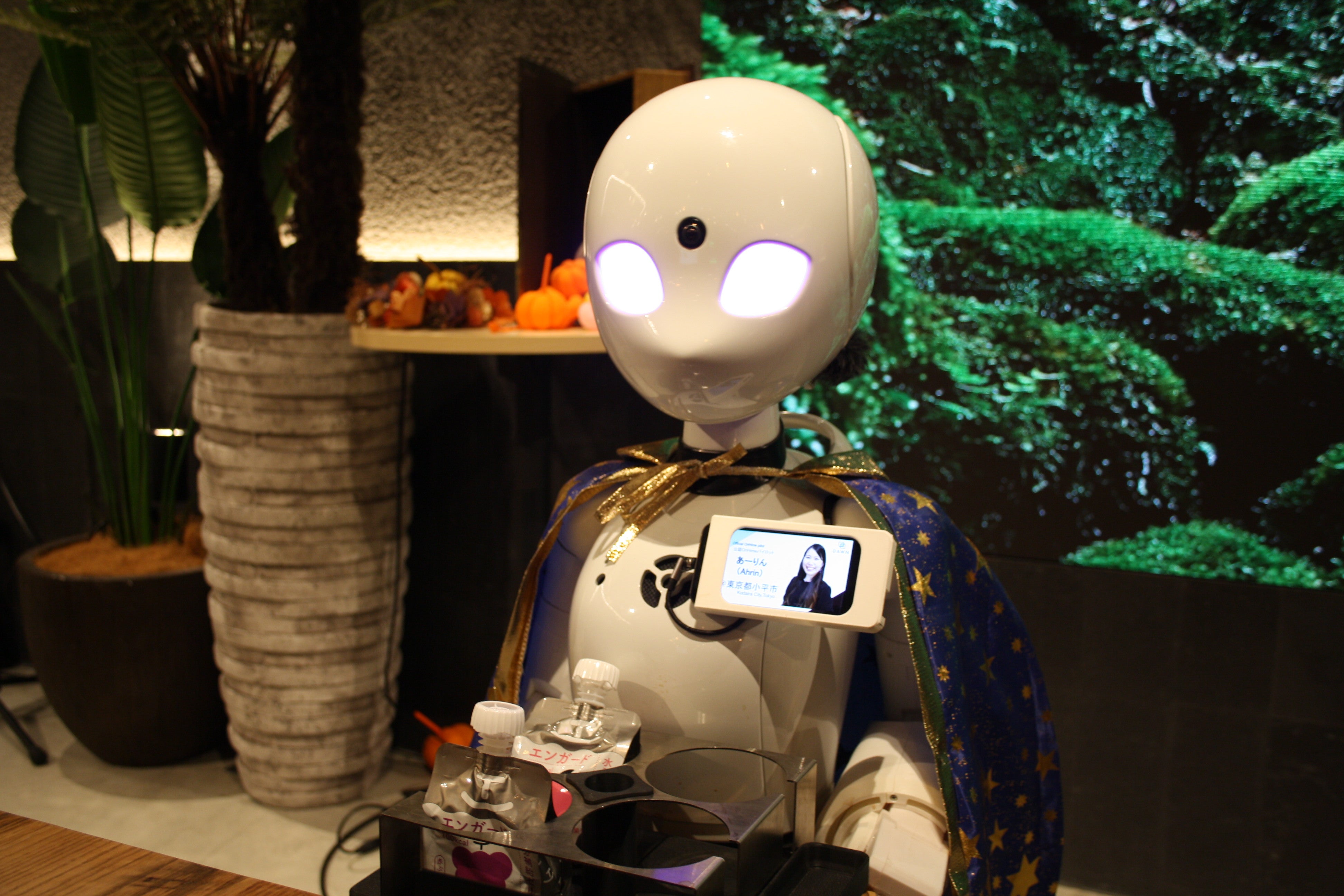

At the Dawn cafe in central Toyko, diners are greeted as they come in the door not by a person, but by a robot avatar. It has a friendly voice, two arms with which to gesticulate for emphasis, and a smooth face modelled on a Noh mask from traditional Japanese theatre.

Another robot accompanies the diner at their table, taking their order and engaging them in friendly chat about their day or, as is often the case with tourists, their visit to Tokyo. And finally, a third robot brings them their coffee, carrying a tray up to the table.

As would be expected from a country that has been pioneering advances in this field since the 1970s, Japan is home to a number of different robot cafes. But while others utilise high degrees of automation with AI-powered machines functioning like upskilled roombas, things at Dawn are very different.

Each of the robots is being controlled by a human – or pilot, as they are referred to by creator Kentaro Yoshifuji. Using a phone, tablet or even just technology to track their eye movements, they can control their robot from anywhere in the world, speaking through them to interact with customers and steering them through the cafe floorspace.

Yoshifuji doesn’t say he has invented a robot – he says he has invented “teleportation”.

Robots and their pilots make up a large portion of the staff at the Dawn – there are as many as 90 on the company’s roster – though the food and drink preparation is still largely done by humans. But it means that if on any given day if there are half a dozen staff visible at the cafe, at least that many are also being employed remotely from their homes.

One thing the company is keen to emphasise is that this is not only a solution for disabled people. The Independent meets one member of staff – via their OriHime robot – who lives in Italy with her husband. She explains that the job helps combat the homesickness that crept in after a decade as a Japanese expat in Europe. By meeting people in the cafe in Tokyo, by teleporting there a few times a week, she maintains a closer connection with her home country.

At one table are Yariv and Anat, visiting Tokyo from Israel with their three children. They are friends with one of the members of staff yet even then found the concept took a little getting used to.

“It’s a little bit strange at first,” Anat says. “We were just sat talking with the kids and then suddenly there’s someone else there. But after that it was really cool. And what’s important is that it is something worthwhile for them [the pilots] as well.”

Heron and Nallely Trejo, software engineers from Mexico who live in the US and are visiting Japan for a two-week holiday, said they found the story behind the robot cafe “really inspiring”.

It’s a model they could see working to improve accessibility in the US and elsewhere. “This is something that should be everywhere,” Nallely says.

The cafe opened in 2021 at a time when Japan had in place a series of strict rules around social distancing in public, though it never underwent a full Covid-19 lockdown. It’s easy to see why it quickly became a hit – there’s no chance of catching Covid from a waiter who isn’t really in the room with you. Or are they?

That question of what it means to be truly present is part of the foundation of OriHime, the name given by Yoshifuji to his robots. He came up with the concept as a student studying robotics when he felt unable to attend class. For years since high school he had used a wheelchair, saying he had a medical condition which doctors struggled to find a cause for that eventually made it impossible for him to leave his room.

Yoshifuji’s teacher said he would fail his class if he didn’t attend in person. “I said, Can we just use Skype? He said ‘No’, right. So then I scanned my face and made a mask, and I used this to attend my teacher’s classes as a robot. I listened to his lectures, and I also raised my hand to ask many questions, and maybe the skin is mine and the hair is also mine. So then you have this question, is this really not me? And I asked my teacher, what is attendance?”

If OriHime were created as a tool to help Yoshifuji and others attend school and university, it quickly became apparent that this wasn’t enough. “When [people with disabilities] graduate from school they cannot find a job. They don’t have anywhere to go to work after graduation, and their employment rate after graduation is about 5 per cent. The ratio going to college is about 3 per cent.

“Universities, workplaces and cities and towns are designed based on the assumption that you can move. And we believe that if our body becomes immobile because of a car accident or disease… if we are not able to leave our bed, then we cannot move anymore. And when we cannot move our bodies, we feel that we can do nothing, and then we will have negative thinking, and we will lose purpose in life, just like I did when I was younger.

“It can lead to loneliness, to dementia and also depression. So we are trying to solve these issues through OriHime.”

The cafe struggled financially in its first two years given the steep up-front costs involved in the tech, and there were various teething issues, not least the struggle to set up a fail-proof network connection for the robots. Pilots also had to be coached not to be “too polite”, Yoshifuji says – otherwise people just assumed they were AI.

But he says the cafe has now made a profit for the second year running, a key proof of the viability of the model that has allowed the company to consider opening more branches. It has already run successful pop-up cafes all over Japan, helping awareness and support for the concept grow.

Yoshifuji has much broader ambitions for the difference his avatars can make to Japanese society – he envisages them being used throughout the country’s schools, colleges and major offices, breaking down the mobility barriers preventing higher numbers of disabled people completing their studies or joining the workforce. He hopes to see his pilots “graduate” from working at the cafe to finding even better jobs elsewhere, thanks to the doors the OriHime can open.

Since the golden age of Japan’s post-war economic boom, robots have been deployed to improve efficiency in almost every industry that involves manufacturing. But there’s a sense that such innovation could only take the country so far, and growth has stagnated since the 1990s. The shortage of workers, not helped by tight restrictions on all kinds of immigration, is just one factor holding back the economy.

Government figures suggest there are almost 10 million people in Japan with some form of disability, roughly 7.6 per cent of the population, and as of September 2024 there were 36.25 million people in the country aged 65 or older.

“There are many people with disabilities in Japan, and the companies also have to follow rules to employ people with disabilities, but they don’t know how,” Yoshifuji says. That’s where his robots could make a difference, he suggests. If robot avatars can help even a small portion of these demographics get into the workplace it could make a big impact, both to their lives and to the country.

Professor Takahiro Ueyama, chief executive member of the Council for Science, Technology and Innovation in the Cabinet Office, says Japanese innovators have long been more interested in advancements for the benefit of society than making their own fortunes. “We raise the slogan that nobody should be left behind, whether that’s the ageing population or people with disabilities. And people expect that the development of science, technology, can [improve] these kinds of people’s welfare.”

He also welcomes radical solutions to overhaul a Japanese workplace culture that has been slow to adapt to changes in the world around it. These are issues, he says, that “cannot be solved in one moment”. “It takes so much time. It is not only that we need a lot of new technologies, but also that the mindset of the people can adapt to new technology.”

For the country to fully realise the potential of a technology like OriHime, corporations and civic society need to rethink their structures, be open to change and – like Yoshifuji’s teacher – be persuaded to shake up their definitions of what it is to be present and contributing to the workforce.

Changing mindsets has always been harder than inventing the robots themselves, Yoshifuji says – and that’s what makes the cafe so important. “In principle, I believe that new ideas are not accepted. It’s not something that’s understood. But when you make something, when you bring it to life, then some people will accept it. And then people will start to understand.”