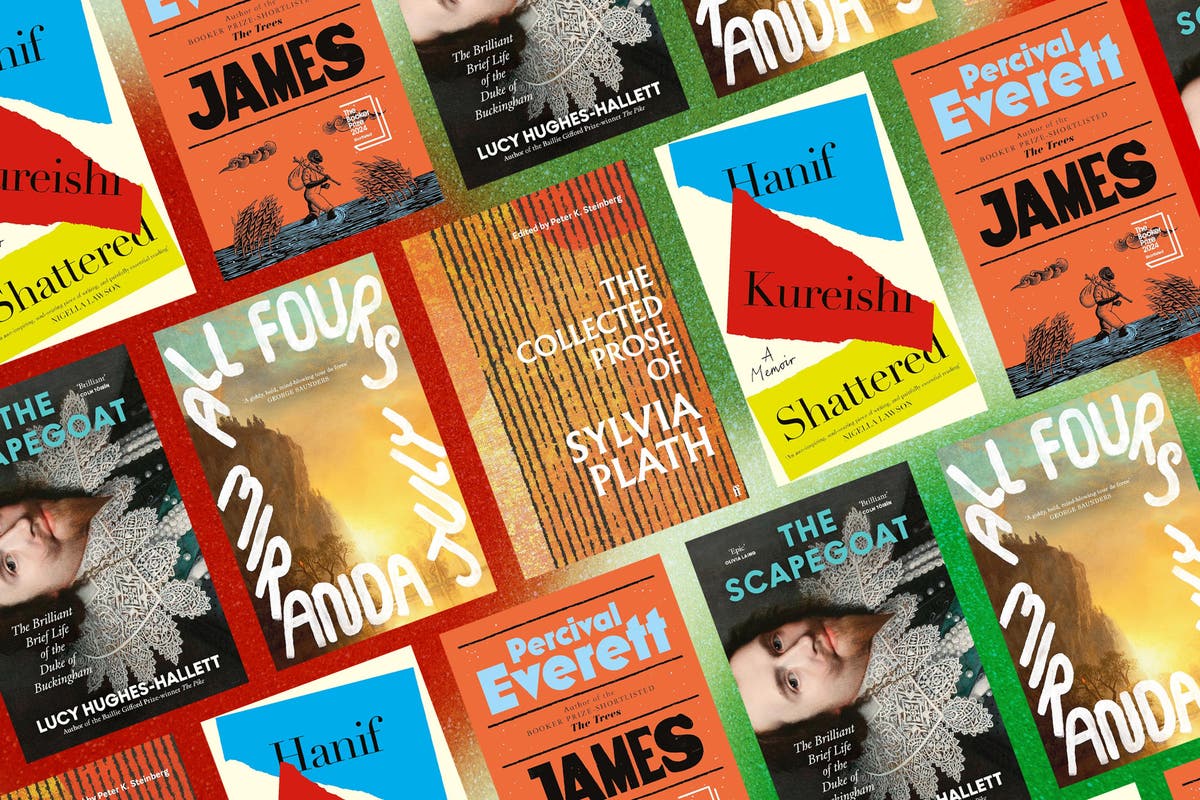

Books are the best kind of Christmas present, and we don’t want to argue about it. When you give someone you love an unputdownable novel, a juicy biography, a captivating history book or a set of letters or poems, what you are also giving is hours and hours of pleasure. That’s why five of us writers are sharing our top five suggestions for great books to give as gifts this Christmas. Just try not to steal them all for yourself…

Geordie Greig, editor-in-chief

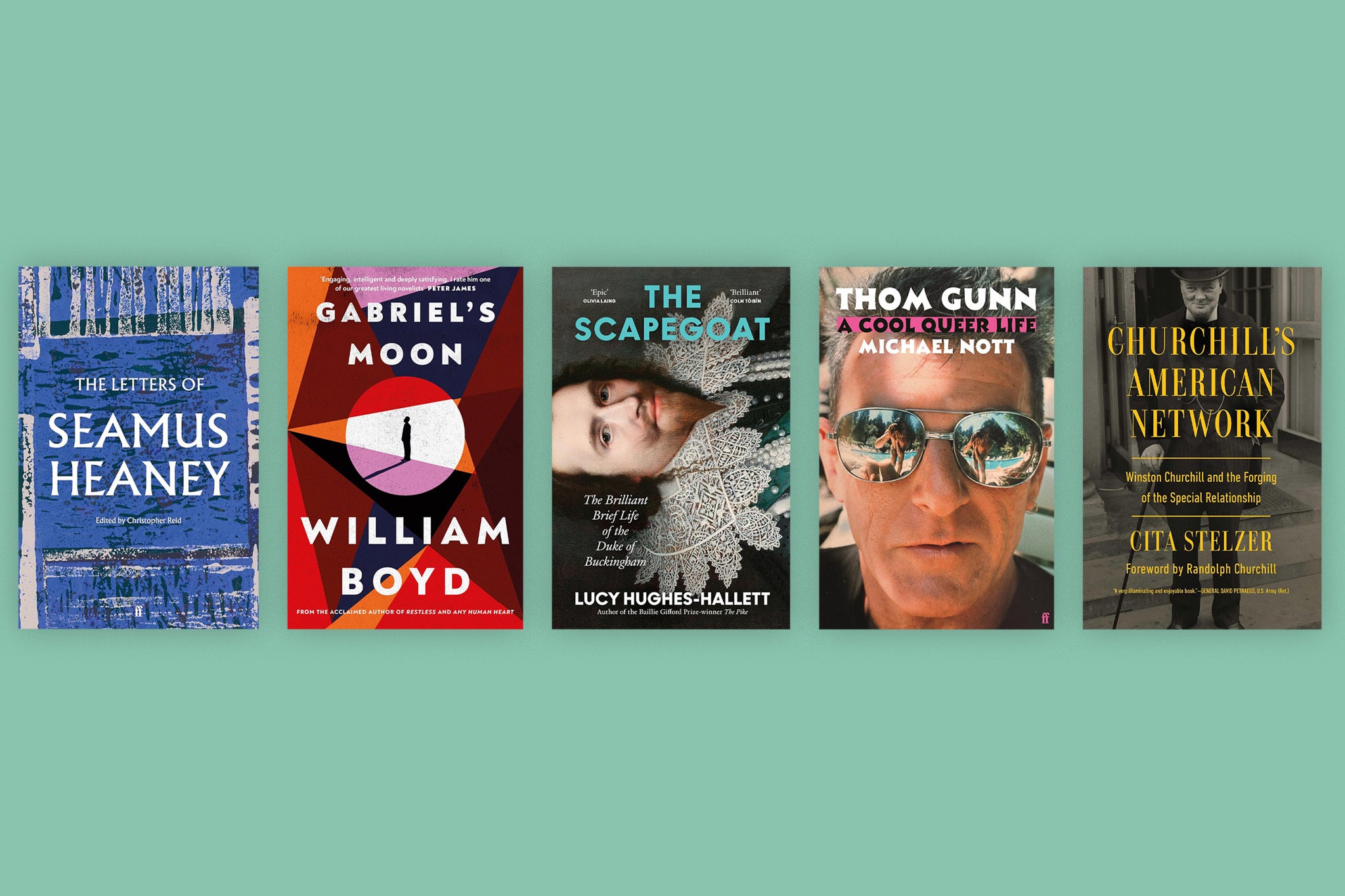

The one snag with William Boyd’s Cold War spy novel, Gabriel’s Moon, is that it is almost too seductive; it made me read too hungrily, too fast. Its crafted prose deserves savouring as much as its addictive pace. In Sixties London, a travel writer – aka our accidental spy hero Gabriel Drax, haunted by dreams of his mother dying in a fire – finds disturbing revelations about his family as he takes an unscheduled turn, one that leads him to assassins and perilous risks. Boyd provides him with a drôle humour and a sense of laissez-faire as Drax inadvertently becomes the most unlikely spy – not exactly giving Bond a run for his money, but as diverting and memorable as 007 (if more accident-prone). What Boyd… William Boyd has written undoubtedly reinforces him as one of Britain’s most talented and readable novelists writing today.

As Keir Starmer ponders his recent trip to Washington DC, he would be wise to read Cita Stelzer’s revelatory book, Churchill’s American Network. This assured American academic, who brings fresh revelations and insights galore to her zingy rollercoaster of a chronicle, shows how Churchill’s colleagues and friends helped push our foreign policy in Britain’s favour during the Second World War. Her masterful piece of reportage demonstrates that, as is so often the case, it is as much who you know as what you know that can truly be advantageous – something, we learn, that Churchill proved in spades. Earning lucrative speaking fees to support his lavish lifestyle, Churchill became the ultimate networker irrepressible at singing for his supper. An indefatigable reporter herself, Stelzer has gathered contemporary local newspaper reports of Churchill’s lecture tours in many American cities, as well as interactions with leaders of local American communities – what he said in public, what he said at private meetings, how he comported himself. It is comprehensive and compelling.

Lucy Hughes-Hallett has served up a delicious, grippingly paced tale of rogues, riotous sex, regicide and realpolitik with The Scapegoat. Here, scandal occurs on an epic level at every turn of the life of Charles I’s favourite, George Villiers, who became elevated through seductive charm and plotting to become the Duke of Buckingham. He shared the king’s bed and his favours. He was enriched and had privileges bestowed on him like no other royal favourite before or since. The details of intimacy and the inner workings of a corrupting court are brilliantly and sometimes shockingly told in a historical biography that brings sex and power, dazzling charm and blind ambition together to paint a remarkable portrait. It’s a totally compelling story of decadence and political dalliance, which culminates in a disturbing end for this handsome buccaneer who flew too close to a monarch who truly believed in the divine right of kings. I have not read for many years a historical biography that was so engrossing or innovative; its speed-dating 100-chapter format – some less than a page – provides a cornucopia of revelations that kept me riveted at every turn.

The first biography of Thom Gunn, A Cool Queer Life by Michael Nott, makes a compelling case that this undervalued Brit poet, contemporary of Ted Hughes, is one of the most significant poetic voices of the last 50 years. When I interviewed Gunn in San Francisco in the 1990s, where he had moved four decades previously, he stood out as one of very few people to write a masterpiece on Aids with his volume The Man with Night Sweats. This biography tackles in detail his drug use and serial promiscuity, and the emotional upset caused while living a commune life in his house with different friends and lovers. Technically brilliant in his verse and always disciplined, Gunn nevertheless had some rough spills in life: despite a seemingly conventional upbringing in Kent, his father a successful newspaper editor, the poet’s suburban childhood was upended when a teenage Gunn discovered his mother at their home after she took her own life. He himself was found dead of an overdose aged 74. In 1954, his first book, Fighting Terms, was hailed as a Neo-Elizabethan poetic masterpiece in thrall to Ben Johnson, and this biography now hails him as a 21st-century seer on Aids, drugs, motorbikes, leather gear and addiction. It’s an eye-popping account by an astute and clever biographer who writes convincingly of how, through Gunn’s poems and private life, we see the USA alter its morals and laws on sex and drugs.

Seamus Heaney, Nobel Prize winner, poet, sage and playwright, was incapable of writing a dull word. He was a master craftsman who wrote what he saw before him to make us feel what affected him, be it pens, spades, pigs, calves, ancient burials or the classical world. A shopping list by Heaney would carry weight or humour, which is why his letters being published is an event; 800 pages of The Letters of Seamus Heaney is full of quirks and jewelled phrases, all sculpted from his generous spirit. It is as if when he had dipped his pen in ink he was seemingly powered by angels. Family letters are omitted at their request, but his musings to other poets, and to his publishers, all have the tang of a truth being told. An appetite for the complete letters at a later stage is now whetted, as the personal ones are likely to be moving and significant. Famous Seamus had a divine gift which brought him the Nobel Prize, and these letters further bring alive the man. I dipped and I supped long, and felt it was a mighty meal of sustenance and wise observations, sometimes also laugh-out-loud funny. Even his letters to his publishers have a sense of the man: all heart and kindness with the intellect of a giant.

Robert McCrum, literary critic

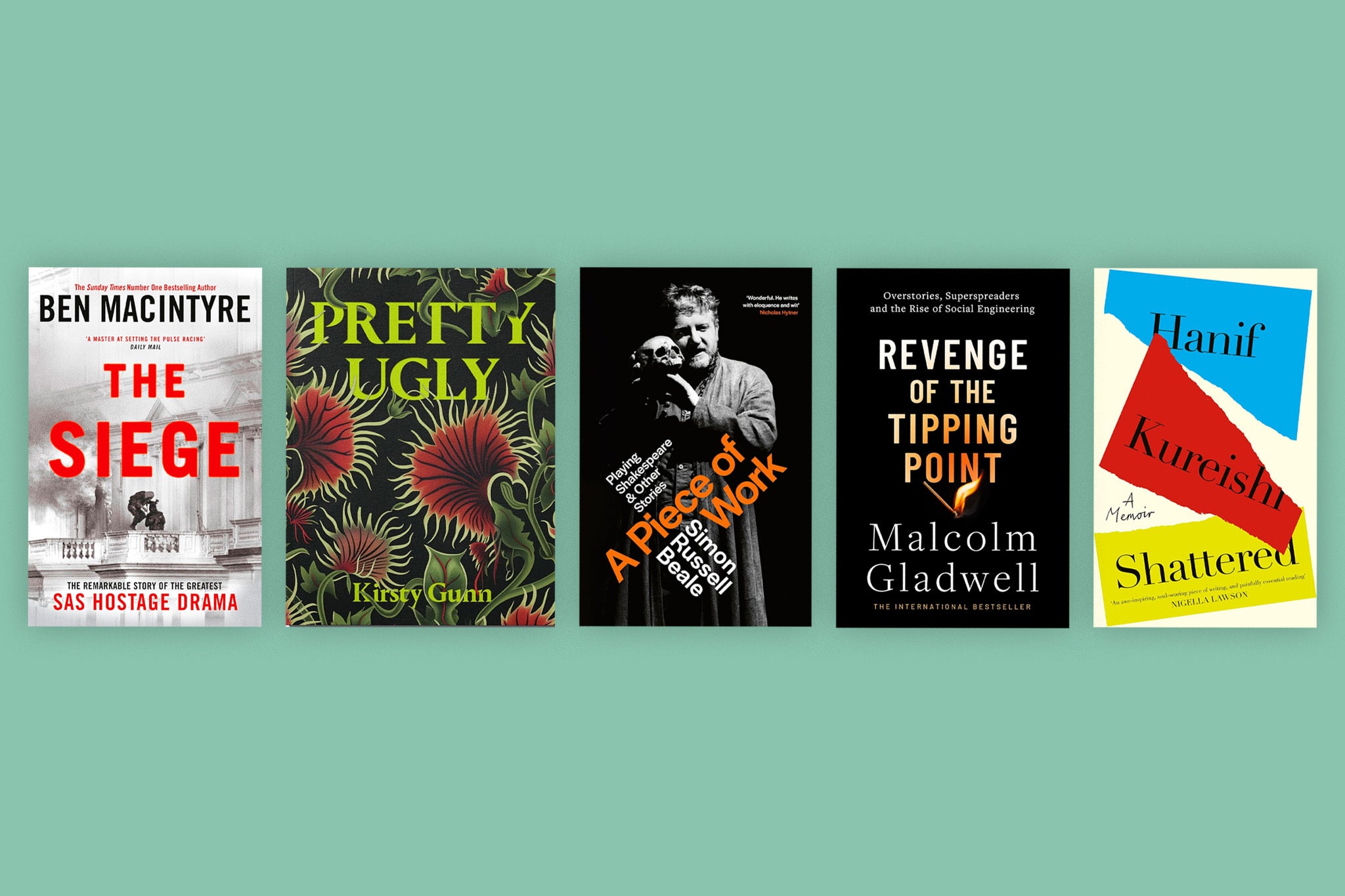

Simon Russell Beale’s A Piece of Work is a rare and enthralling theatrical self-portrait by a great actor who recalls a lifetime devoted to performing many great Shakespeare roles with modesty and candour. Witty and perfectly-pitched as well as a revelation, Russell Beale is as captivating in print as he is on stage. Magic.

How would you respond to terror when you have no choice? The Siege by Ben Macintyre is a mesmerising reconstruction of six days that put the SAS in the TV spotlight: that gripping stand-off with international terror at the Iranian embassy in May 1980, an event that helped define Mrs Thatcher, and now part of our national myth.

The autobiography of 2024: Shattered by Hanif Kureishi. It’s a heart-breaking account of the writer’s life-changing paralysis, confronting a terrible medical emergency with wit and brio in this masterpiece of British stoicism. Intimate, brave and uplifting.

Elsewhere, 25 years after The Tipping Point transformed our understanding of popular consumption, the perverse and baffling way “little things can make a big difference”, Malcolm Gladwell returns to the fray with Revenge of The Tipping Point. His message: social epidemics are a new and troubling kind of social engineering. And finally, Kirsty Gunn is renowned as the author of Rain and many other fictions. Her brilliant short stories, in the new book Pretty Ugly, are always startling in their ambition, and provocative in their detonation of shock and revelation. A rare and beautiful collection that’s not quite what it seems.

Jessie Thompson, arts editor

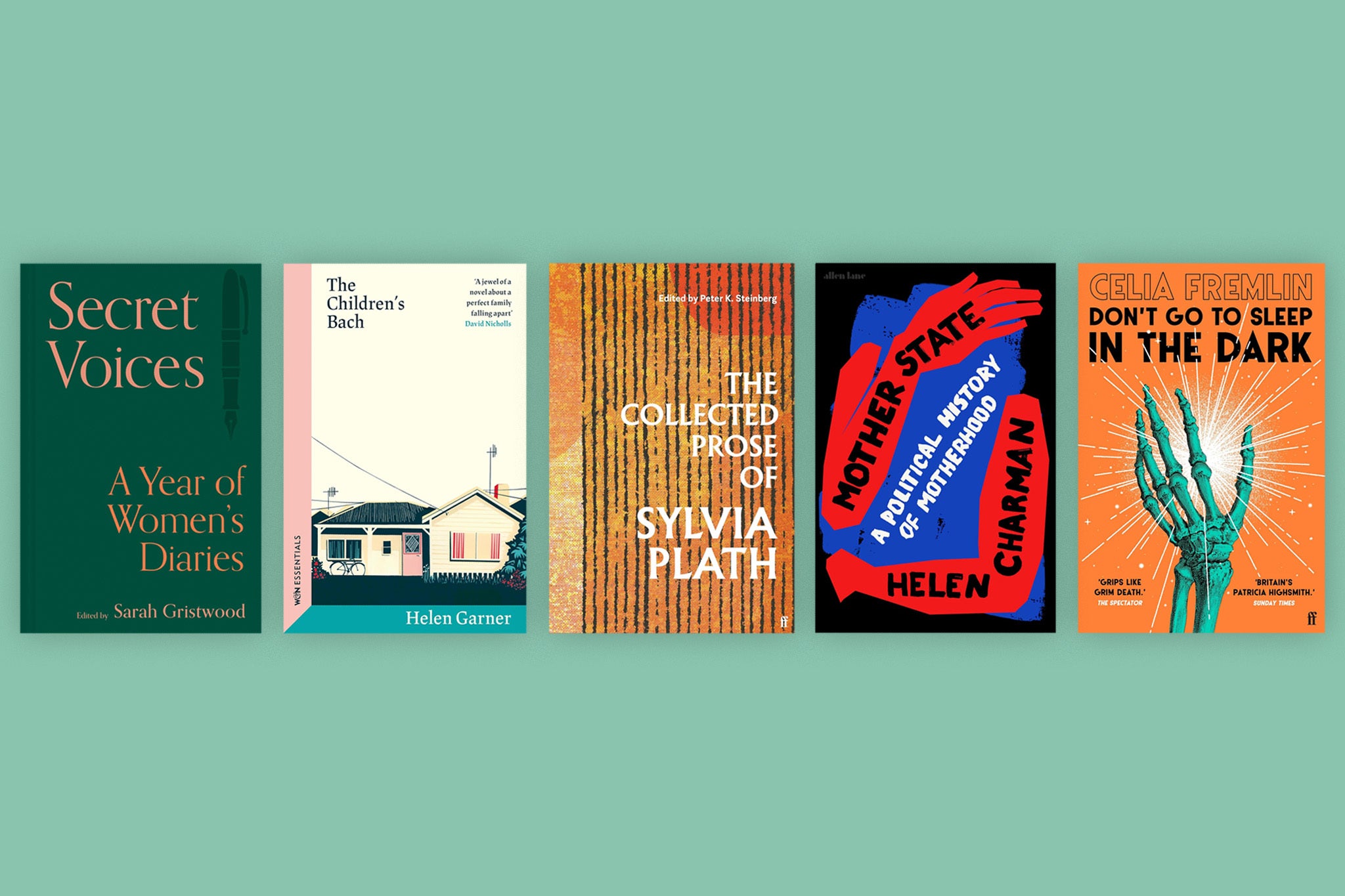

I always want to give great novels as gifts, but some of last year’s best – The Bee Sting by Paul Murray, Demon Copperhead by Barbara Kingsolver – were such hefty doorstoppers, I worried some might feel I was being a bit oppressive. Fortunately, the novel I’d love to give everyone this year is a svelte 176 pages and you can read it in a day. The Children’s Bach by Australian writer Helen Garner is about a marriage that has become too safe, ripe for being destabilised by the reemergence of a figure from the past. It was republished in a beautiful new edition this year, along with two of Garner’s other works, with a new introduction by David Nicholls; it is as superb as the many euphoric blurb quotes suggest.

Also undergoing a bit of a revival is British mystery writer Celia Fremlin, and a recently published collection of her short stories, Don’t Go to Sleep in the Dark, makes for a wonderfully eerie winter read. It’s published by Faber, who have also just brought out a beautiful edition of The Collected Prose of Sylvia Plath, a brilliant gift for anyone wishing to see the famously misunderstood poet from a new angle. I loved Secret Voices: A Year of Women’s Diaries, an anthology of the diaries of women over the past four centuries, edited by Sarah Gristwood, which features Louisa May Alcott, Beatrix Potter, Virginia Woolf, Katherine Mansfield and Barbara Pym. Perfect for dipping in each day. And finally, one of the most exciting trends in non-fiction has been an emerging genre of new intelligent writing about motherhood. Mother State: A Political History of Motherhood by Helen Charman is an excellent new addition, taking readers on a journey from Margaret Thatcher to Kat Slater, to anti-nuclear campaigners and the wives of striking miners.

Victoria Richards, voices editor

On driving to an old school friend’s birthday dinner in Essex, recently, I grabbed a well-thumbed copy of Miranda July’s All Fours from the shelf and unglamorously stuffed it into a gift bag. With profuse apologies, I explained that I hadn’t had the chance to get to a bookshop to buy her a new copy – but that it was urgent that she read it. Imperative. And so, she received mine: tear-stained and dog-eared; a map to the passages that moved, shocked and surprised me. To say I will be buying this book for Christmas for every single one of my closest female friends now that we’re well into our forties is no understatement – and if I can’t buy them a copy, then they’ll be getting one of mine.

Why? Well, July’s tale of a woman who abandons her job, husband and child to drive to a bland hotel room just 30 minutes away, where she experiences a profound and transgressive shift in self – and a reawakening of desire – is not just interesting reading, it is vital reading. It is magnificent, odd, wildly relatable and laugh-out-loud funny: the perfect gift accompaniment to Leslie Jamison’s memoir Splinters: Another Kind of Love Story – another of my Christmas picks.

While July offers a fictional exploration of perimenopause, divorce and erotic rediscovery, Jamison shares a moving account of rebuilding a life at the end of a marriage… an experience Amy Key wishes for, yet ultimately abandons, in her own memoir Arrangements in Blue: Notes on Love and Making a Life. In this haunting story set to the strains of Joni Mitchell, Key recounts a life spent in solitude and poses the key question: is it possible life without romantic love isn’t so bad?

Considering love – and life – is only enhanced by looking at its shadow side: which is why I’m going to give Hayley Campbell’s incredible book All the Living and the Dead: A Personal Investigation into the Death Trade to those I care about. Campbell relays a fascinating, provocative and strangely uplifting series of interviews with those who take care of us when we die: from embalmers to funeral directors, bereavement midwives to executioners.

Lastly, Amelia Loulli’s debut poetry collection Slip – the first ever collection dedicated to abortion – should be mandatory reading in 2024. One in three women in Britain will have had an abortion by the time they are 45, yet it’s still technically illegal – while in the US (as elsewhere) women’s rights to bodily autonomy are being slowly stripped away. Loulli’s poetry is far more than pretty prose – it is a war cry. She opens the collection with the words: “I’m going to tell you what happened” and that is precisely what she does. It’s down to all of us to listen.

Katie Rosseinsky, senior culture and lifestyle writer

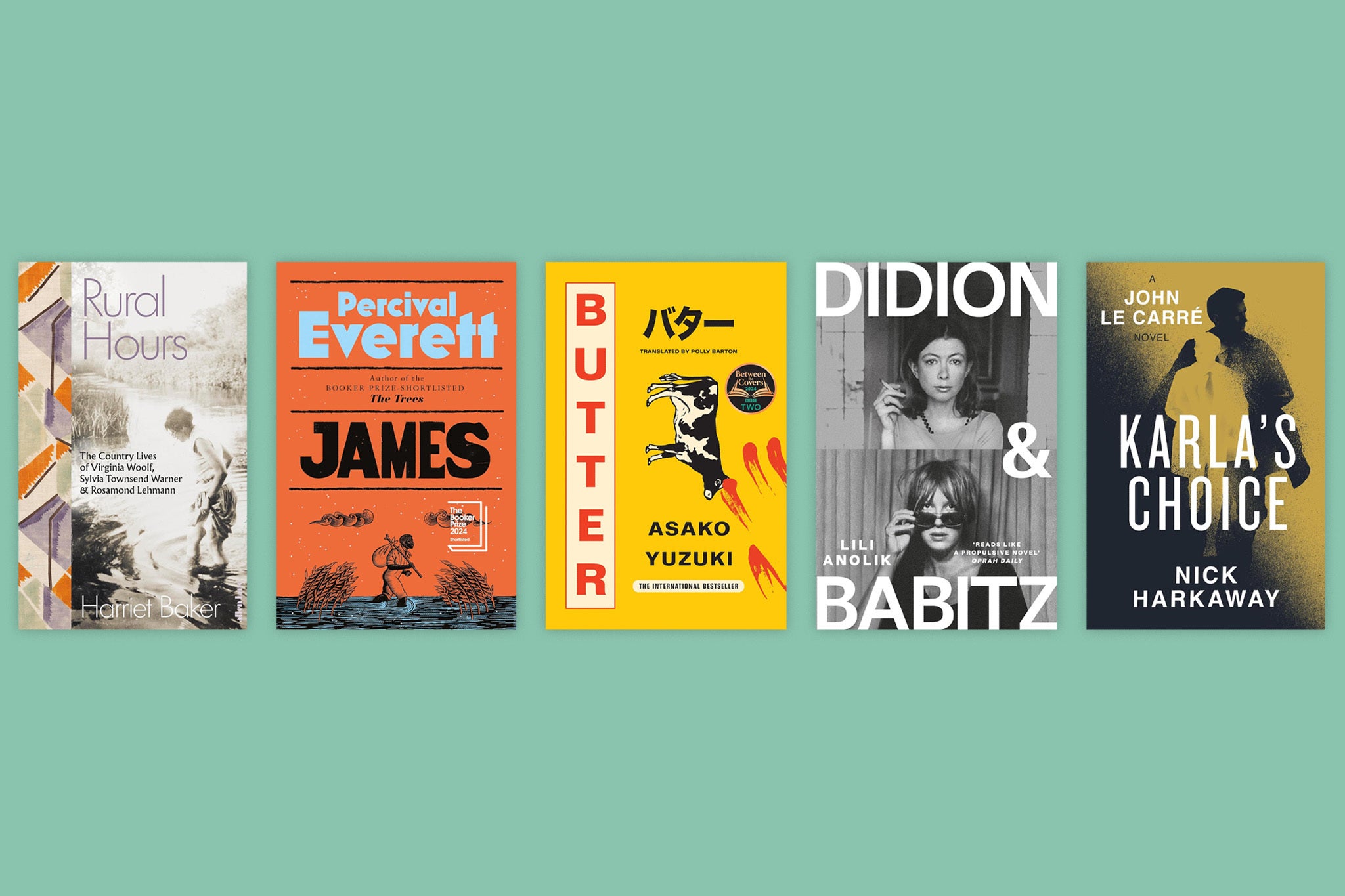

It may have missed out on the Booker Prize earlier this month but, in my humble opinion, James by Percival Everett is well deserving of a different accolade: the novel you should buy for all your literary-minded friends and family members this year. The publishing industry is flooded with literary retellings right now, but it’s rare to see them done with this much panache and wit. Everett revisits the events of The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn from the perspective of Jim, the runaway slave, turning Mark Twain’s classic upside down as he goes.

Speaking of clever use of iconic source material, you should press a copy of Karla’s Choice by Nick Harkaway into the hands of any thriller aficionado. Harkaway is the son of the late, great master of the spy novel, John le Carré, and Karla’s Choice sees him pick up that mantle, imagining what happened to the legendary operative George Smiley in the decade between The Spy Who Came in from the Cold and Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy. I was, I’ll happily admit, highly sceptical, but Harkaway has done a wonderful job, balancing a tricksy plot with a satisfyingly grimy evocation of Sixties London. Butter by Asako Yuzuki is perhaps more of a slow burn, but equally satisfying. It’s based on a real-life case and tells the story of a Tokyo journalist who becomes obsessed with Kajii, a woman accused of seducing lonely businessmen with her lavish cooking, then murdering them. It’s the sort of book that your lucky recipient will open on Christmas Day and be gripped by for the rest of the holidays.

I always find that the hazy, lazy period between Christmas and New Year is a good time to catch up on non-fiction (which I don’t always have the attention span for during the rest of the year). Two brilliant biographies to pass on to your well-read pals are Didion & Babitz by Lili Anolik, a gloriously gossipy exploration of the friendship and rivalry between LA legends Joan Didion and Eve Babitz, and Rural Hours by Harriet Baker, an exquisitely detailed account of how the countryside influenced the work of Virginia Woolf, Rosamond Lehmann and Sylvia Townsend Warner.