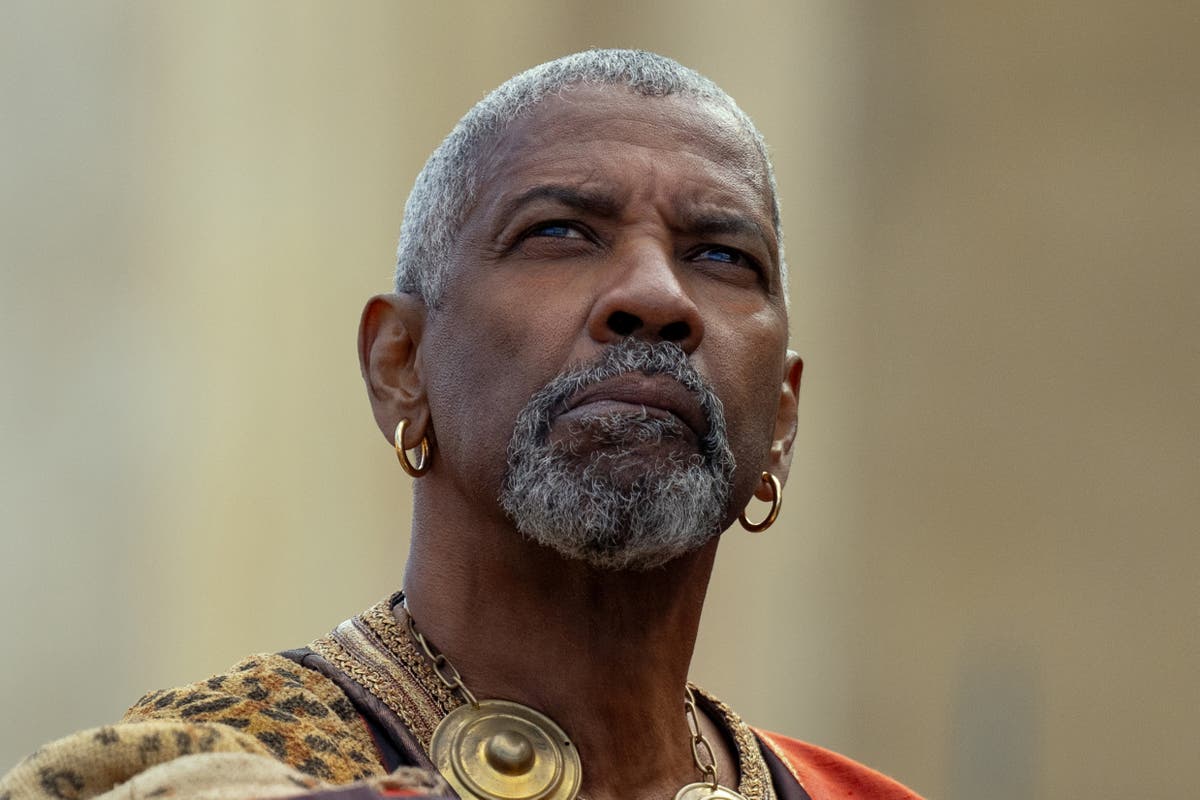

It may have conquered (the box office), but Gladiator II has certainly divided. Ridley Scott’s long-gestating sequel to his 2000 Roman epic has prompted everything from feverish praise to bitter scorn. Even within the pages of The Independent’s culture section, there is discord: critic Clarisse Loughrey gave it four stars, branding it “equal [to the original] in scale and spectacle”, while Patrick Smith threw it to the lions, rhetorically speaking. On one matter, however, pretty much everyone is united: the ineffable charisma of Denzel Washington.

The 69-year-old actor’s performance in the film, as the preening, scheming slave owner Macrinus, has won over even the most jaded doubters. It’s also a milestone for Washington: Macrinus, written to be bisexual, is the first queer character he has played on screen. Gladiator II’s other two major villains – effete, bickering emperors Geta (Joseph Quinn) and Caracalla (Fred Hechinger) – are also bisexual, and androgynous in appearance. Together, they’re surely some of the most prominent bisexual male characters to ever grace a blockbuster of this scale. Why, then, does it feel so disappointing?

Macrinus, Geta and Caracalla are part of a long and storied tradition in Hollywood – the queer-coded villain. Bestowing stereotypically queer characteristics onto a villain is a trope that’s been used in everything from The Maltese Falcon (1941) to Braveheart (1995) to Skyfall (2012). Alfred Hitchcock’s Rope (1948) was a particularly layered and sophisticated example of this trope, placing two gay murderers at its centre; for a rather more crass and objectionable example, just look at the 2006 historical epic 300. Disney was a particularly prolific purveyor of this stereotype: animated films such as Aladdin, Pocahontas, and The Lion King all had flagrantly queer-coded villains. Any individual instance of this may be innocuous enough, but combined, the pattern is insidious.

In Gladiator II, the sheer numbers make it jarring: the prominent queer (or queer-coded) characters are villains, while Paul Mescal’s heroic Lucius is as straight as a Roman road. In a piece for GQ titled “Gladiator 2 is kinda gay”, Jack King wrote that the film’s “queer subtext feels most obvious in how many of its male characters are feminised”, adding: “Most of them are villains, which some might read as retrograde.”

And yet, there is room for equivocation here. Coding a villain as queer – or making it textually explicit – does not automatically equate to homophobia. (Many of those irrepressibly fruity Disney villains were in fact created or shaped by animator Andreas Deja, an openly gay man.) Insisting that queer characters be fenced into a bland, affirming positivity is just as reductive and damaging as making them the perennial villain.

Washington, an actor of superlative depth and control, is invaluable in making sure that Macrinus never devolves into a flat stereotype, no matter how flamboyant the monologue. The same cannot be said for Geta and Caracalla, who are thinly drawn and less compelling. More than anything, the sexual politics of Gladiator II felt as if they just hadn’t been given all that much thought. This is, after all, a film in which gladiators battle in a Colosseum filled with live sharks – the rigours of the story ultimately play second fiddle to visceral spectacle. As such, the film’s reliance on queer villainy tropes doesn’t seem so much like a calculated slight as simply the woolly result of not considering implications.

It’s hard, though, not to see Gladiator II as a missed opportunity. Ancient Rome is one of the only historical periods regularly recreated on screen where you can depict queer characters living out in the open. It’s a shame that even in a film that was – in the words of our review – “pure camp”, there was still so little to root for.

‘Gladiator II’ is in cinemas now